Think of memories that disappear, memories evanescent as infancy, childhood, youth, a glass of wine, a kiss. Memories that blend in so well we seldom notice them.

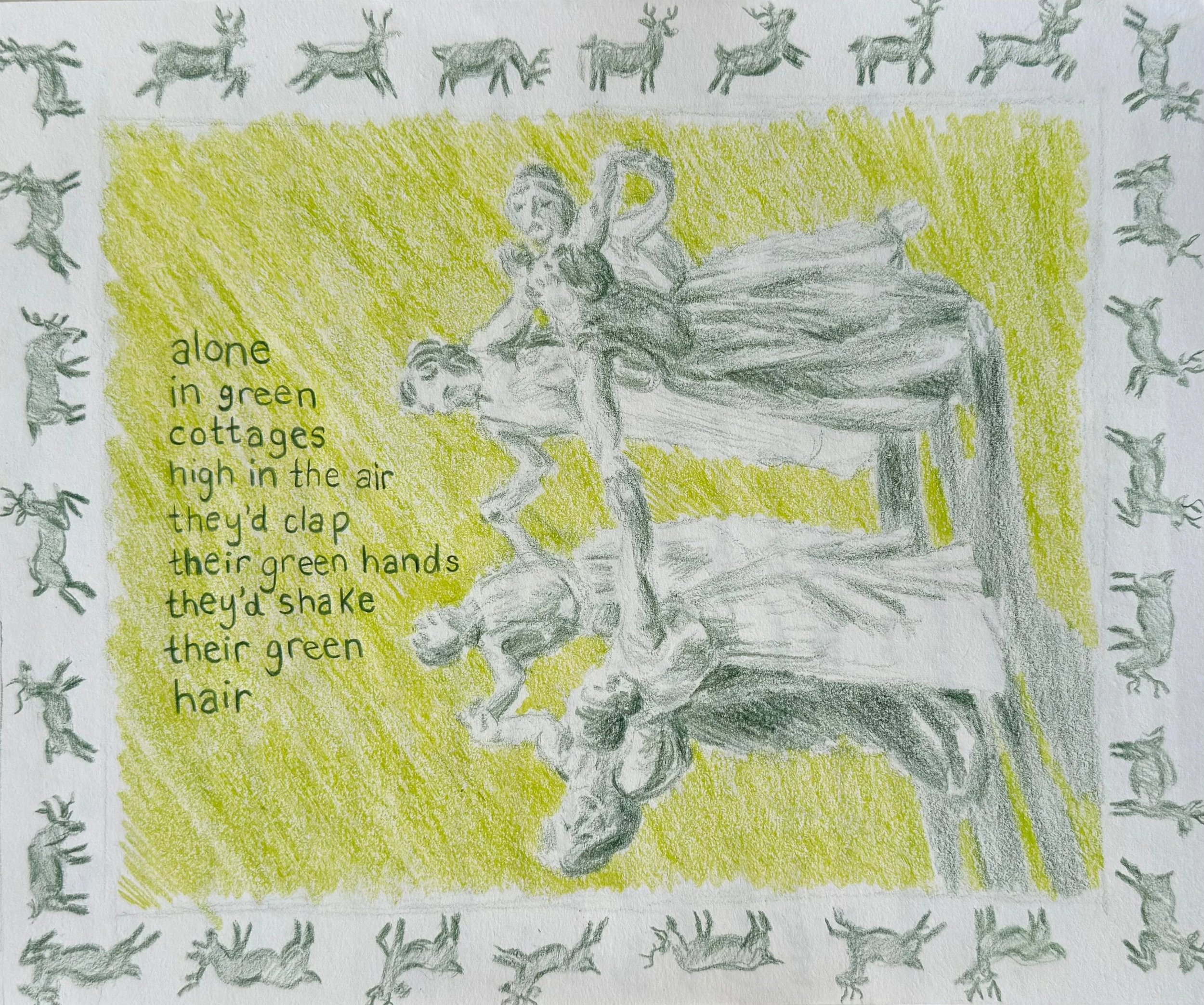

Growing up, I lived in a quaint, storybook neighborhood full of twisting, swerving roads. On each path, I was surrounded by tall pine trees that embraced, surrounded, and wrapped around me. The trees lived alone in green cottages high in the air, and I knew what would happen if I climbed way up — they’d clap their green hands, they’d shake their green hair, they’d welcome me. As if kissing the sun, the harmony of the trees’ breath reached my inner being.

I spent most of my time outside, attempting to preserve my naive mind. In my fairytale of mythical friends, I felt peace, from the bright red dahlias to the moss growing on each rock that I jumped to and from. I would examine the green, spongy, soft forms and rub my hands all over them to feel closer to Mother Nature. One late afternoon after an outburst of temper over some inconsequential offense, I ran out of my house amid my tantrum. Racing through the forest that lay just behind my river’s dwelling, I did not stop until I was sure no others had followed me. I lay back on a tree stump, crying my eyes out, overcome with tears and letting go of all the grief my little heart carried. I stared at the sunbaked dirt and stone roads, and each yard, a field of wild grass. My best friend Evie suddenly appeared beside me. She sat down on a tree stump and sighed. We watched, together, the snowshoe rabbits who ran wild, a tawny doe with a freckled child, and swooping wrens alongside bumble bees.

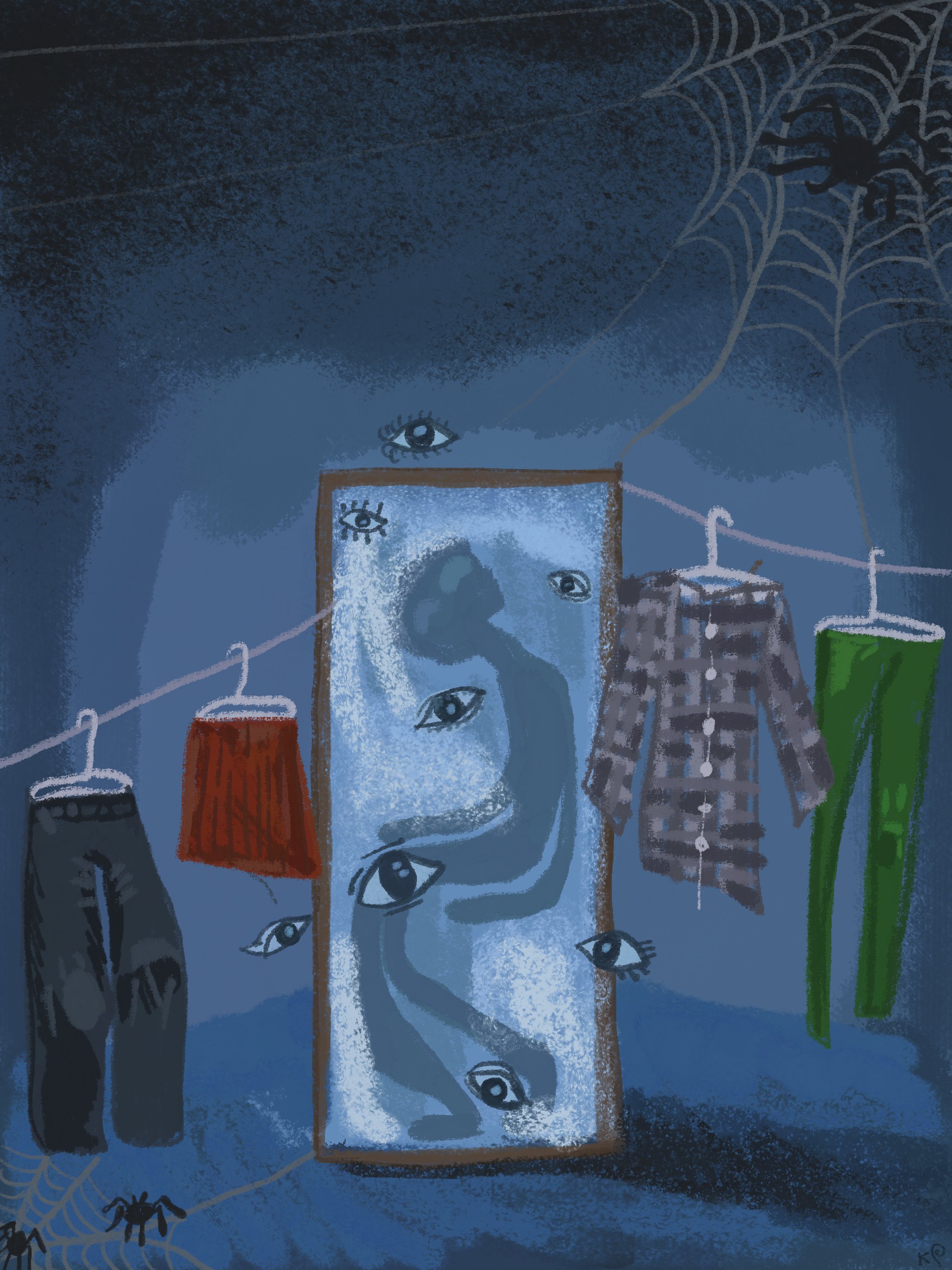

Evie lived right across the street from me in a modest brown house with creaky stairs leading up to the front door, on which I often grated my bare feet. I ran over, without my mother’s knowledge, to dance to Mamma Mia songs and play dress up. We designed our own clothes, often wrapping Evie’s mother’s scarves across our chests, and blankets from our waist to feet to look like Ariel. Or grabbing knives from the kitchen, cutting a small piece of paper to place over one eye, with a hat made from newspaper to play pirate.

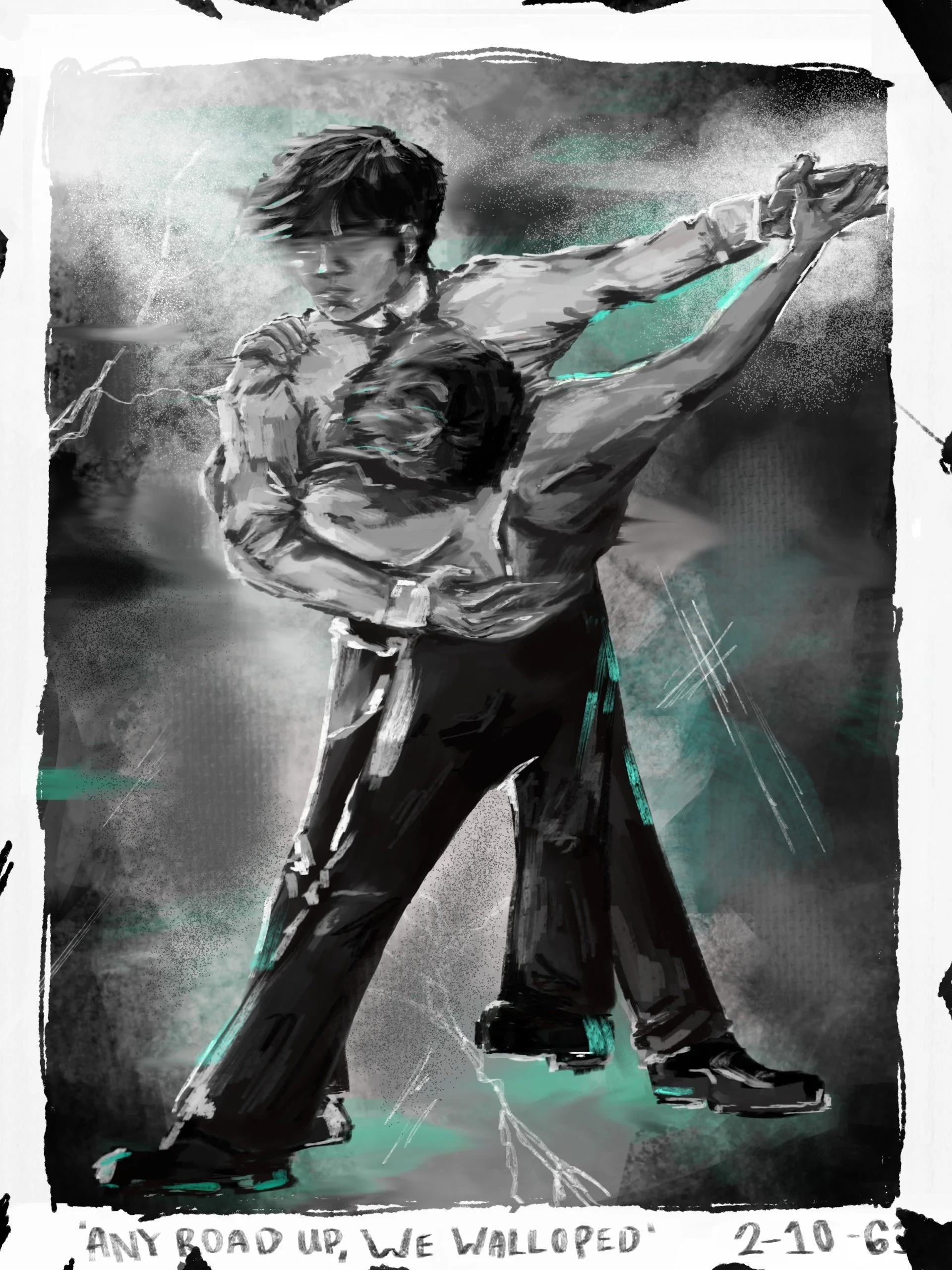

In those formative years, I spent a lot of time running through my neighborhood causing mischief. Evie and I would race outside to bike and jump over rocks and try mysterious berries. Our mothers told us that while the deer that leaped through our neighborhood, never wary of moving vehicles, easily ate the berries that populated our bushes, they were poisonous to humans. Little did they know that we were children and not obliged to the same rules as adults. So we chewed and spat out the enticing, intensely red berries, imagining that the poisonous fruit contained hallucinatory elements. We fantasized we were deer, galloping on our feet and jumping in front of cars, giggling and smiling at one another the whole time.

Some days, Evie and I assembled a group of mischievous kids who lived in our community. We all biked to our neighborhood’s beach and playground to jump on the water trampolines and glide on the zipline or play on the swingset until our legs got tired. Other times, we knocked on doors and then fled, twisting our ankles and pushing one another to avoid being the one who got caught. Evie and I occasionally escaped the wrath of the boys and the idiocracy, the roguish lack of maturity of the group, to plan our own schemes in our own impish ways.

On a particularly dull day, Evie suggested we go into Jean’s, our neighbors', attic, to rummage through her things. I never had a basement or attic, so I was afraid of what happened in there. Especially Jean's. She seemed aloof, unsightly, and perhaps cruel. I never had a liking for older women; they reminded me of when childhood comes to an end, and a plain, ugly life begins. I would be grumpy, too, if I couldn’t play with grass and dandelions with my friends, and instead had to take care of the kids who played … with the grass and dandelions. I imagined her attic to be dark, dirty, daunting. What was she hiding from us?

Evie had told me there was a ghost in Jean’s attic. She announced it quite casually as we were skipping and throwing rocks at passing cars. “You don’t have to worry, Ray,” she reassured me, “we can capture them as pets; they can help us fight off boys and grown-ups.” I smiled to humor my dear friend Evie, but I never walked past Jean’s house normally after that. Whenever I’d go by on my pink shimmering bike, I was convinced I had caught sight of something in the corner of my eye that made everything shadowy, weird, distorted. I felt I was being watched as the sparkles flickered in the sun and then reflected into a dark abyss. I’d cycle away as fast as I could, looking behind me in terror. The possibility of a ghost, even benign, freaked me out completely. I thought I was a strong girl that could combat any enemy, but after all, I was still scared of spiders. From all my antics, I knew karma would find me one day.

We whispered on Fridays and Saturdays, when our parents were too oblivious as they drank and sulked in their grown-up obligations, to finalize plans for our delinquent exertions. It was summer; the air was still, and it hadn’t rained since school was out. The brief breezes smelled rotten and forbidden as if the wind blew from some faraway breath of life. Our short legs were covered in beads of salty, sweet sweat — saved by the youth of nonexistent B.O.. We specifically picked a day that made even the shadows wet and mucky. A day so hot that Jean wouldn’t dare be in a home that made her ghosts melt under the oppressive heat.

We knocked passionately on the grand, antique lime green door, leaving my knuckles red and scraped with splinters. With no answer, I turned the knob slowly — its coldness shocking my sticky skin. Her living room slowly came into view as the door creaked open. Immediately, when we stepped in, I let out a loud sneeze — the warm air having intensified the piles of dust that layered her floor. Evie’s older sister, who had been in before to watch a dog, told us exactly where to go: “Find the closet in the big bedroom, the trap door is in the back.”

Our instincts led us to the attic quickly and quietly. We climbed up the attic stairs slowly — each tip-toe softer than the next. Once we reached the top, we nervously darted our flashlights around, searching for the spirit. I pulled out a clown doll from a box and was laughing with Evie when suddenly a presence filled the room. Our mouths were agape. There she was with her black, long hair back in a bun. Her long flowing cotton dress covered with a dark gray apron, and on her feet were laced-up boots. She had Italian features with tanned skin and appeared middle-aged, waiting for the wrinkles to approach. I don’t remember what happened after that. There is a version in my mind where we reached for her, but she disappeared. We ran out, unsatisfied with our findings.

A year ago, I attempted to return to the river, carefully avoiding the sight of Jean’s house. Once I got closer and closer to the river, I shook from nostalgia as tears formed and leaked down my face. I felt alone. I didn't hear any squealing children, I didn’t see any spilled wine from drunk, chatty moms, I didn’t see any footprints from the tawny does. The sun was going down. It was getting late and dark.

I suddenly stumbled and tripped. I fell off a hill I hadn't recalled was there prior and rolled down at a swift speed. My body came to a stop as it hit a rock with a loud thump, soon overtaken by a weak, calming sound.

“My dear, why don’t you let me ease your pain?” inquired the soothing voice.

I looked up from where I was on the ground and saw an old woman with a kind face. I felt at ease and at peace with her smiling reassurance. Behind her, there were a dozen women of her age, dancing and giggling around a fire. Their hands were intertwined, some were cheering each other on, others were laughing so hard their heads fell back. It was easy to miss at first, but something about them was different. They were well-aged with long gray hair that seemed so dull it almost looked like it was fading into the moon’s radiant beams. They had white wax paper-like skin so delicate, a simple breeze might turn each of them into dust. There was a transparency about these women that seemed like a blur. I could almost look beyond them and see the woods.

“You have gotten so old, and so have I.”

I looked myself up and down, and then I looked at her up and down, stopping at her wrinkled forehead. I felt envious of her humble, sagacious self-confidence. I looked behind her once again to cherish the sight of the bond among those women. Maybe childhood does vanish, but womanhood — womanhood lasts forever.

She interrupted my silence, “There’s someone out there waiting for you.”

I understood it was the eerie, fleeting ghost of Jean’s attic. I ran away to find the trees.