Article and Art by Nalani Wood

Some of us had our first sip of alcohol after a successful heist of our parents' not-so-secret stash of aperitifs, those decadent beverages that we were never allowed to try. Maybe it was a bottle of coconut rum sipped straight from the white Malibu bottle. Maybe we got our hands on some wine and strutted around in too-big heels sipping sour grape juice from a wine glass. Maybe it was a sip of whisky at the dinner table, a supervised indulgence meant to prove it didn’t taste good enough to want again. We come into contact with alcohol in the holiest of places, sipping Christ’s blood with your grandma and grandpa in your finest Easter attire. Perhaps you shared a beer with dad, a bonding beverage at the stadium, cheering for your favorite team. Whatever it may be, alcohol often enters our lives innocently. Casual attitudes towards occasional consumption instill a sense of acceptance and trust in a compound that chemically transforms into poison when our bodies digest it.

Everyone has a different relationship with alcohol, a different origin story, a different pattern of indulgence. We partake in plenty of things that aren’t great for us; that doesn’t necessarily make them evil. What’s fucked up is how casually, almost proudly, so many of us drink to get fucked up. We joke about getting wasted, smashed, properly pickled, sauced, hammered, plastered, shitfaced. We tell stories of blacking out like it’s a silly adventure or a badge of honor, rather than a period of amnesia induced by excessive alcohol consumption. Our emotional and physical integrity can easily slip out of our grasp because of a few too many drinks. The “tactical vomit” technique is employed by some to override the nausea our bodies send to us when we have ingested too much poison. While a few fingers shoved down your throat might relieve the nausea, the overproduction of stomach acid caused by irritated stomach lining and subsequent production of toxic byproducts has still occurred.

For many, a few drinks pair well with almost any occasion. Built into so many rituals of life, birthday parties, promotions, heartbreaks, drinking wiggles its way into celebration, grieving, or just a casual Tuesday evening. Crafting a creative cocktail and adding a tasteful shot of some spirit or another isn’t a problem until it is. The issue with drinking, especially for young people, is that it can be such a slippery slope. Getting tipsy often leads to getting drunk, especially in college. People think they need to be drunk to go out, whether for social lubrication or to fend off the cold with a heavy buzz replacing their jacket.

Beyond the broad societal acceptance of overindulgent drinking, alcohol is woven into the fabric of college life in an unfortunate way. It’s how we celebrate, how we flirt, how we decompress and cope. Saying no to a drink is isolating. If you don’t drink, some people will want to know why or convince you to partake, thinking they’re doing you a favor by pulling you into the fun. Social pressure to drink is built into the expectations and realities of most college campuses. College makes drinking feel like a shared ritual of becoming. Choosing to step away from that rhythm is to step outside a strong pulse of campus life. Staying sober isn’t just abstaining; it’s a choice to opt out of the shorthand that so much of college socializing depends on.

Some are drawn to drinking in order to protect their minds from the incessant condition we all share — consciousness. Prehistoric human societies started the substance-induced reality-bending trend, employing psychedelics from ungulate feces in religious rituals. Today, mind-altering substances are not all treated equally within societal circles. For example, MDMA is lauded by some scientists and Molly lovers as a miracle, but is condemned by the FDA as a Schedule 1 substance along with heroin and marijuana. The classification of substances by the FDA, regarding both addiction and health risks, is guided more by prejudice and fear than by scientific evidence. Alcohol is inarguably a kind of mind-altering substance, but is not classified as a controlled substance under FDA regulations. As liberal arts students, we have all discussed how institutional paradigms are influenced by and influence societal paradigms, including the way we approach drinking. When we don’t form relationships with alcohol intentionally, drinking can easily become a shared language of escape and coping, innocently disguised as social bonding.

Drinking is so normalized that people willfully ignore what alcohol is. Classified by the International Agency for Research on Cancer as a group one carcinogen, alcohol is up there with tobacco, asbestos, and radiation. Causes of cancer are numerous and can be difficult to track, given how many other carcinogenic substances are floating around on shelves, in water, and in the air. While cancer research is incomplete, data undoubtedly shows that drinking increases your risk of developing cancer in your mouth, throat, along your digestive tract, and in your esophagus and colon. For those of us blessed with boobs, drinking also increases our risk of breast cancer. Of course, how frequently we drink has an impact on the degree of these risks, and there is inadequate scientific clarity on exact quantities that would be deadly, nor on the contributions of gender and genetics. Some uncertainty surrounding alcohol shouldn’t sway us to minimize the fact that any amount of drinking incrementally increases the risk of deadly health problems. Beyond the cancer risks, alcohol indirectly increases the occurrence of traffic accidents as well.

I grew up on Maui, (pop. 168,307), and knew a lot of people who would combat their angsty teen island syndrome boredom by sneaking out of the house, tapping shoulder in a dark parking lot to acquire some cheap, shitty alcohol to drink in a park. This classic nighttime activity often led to drunk driving. On the North Shore, a few roads are notoriously used as race tracks by drivers making decisions with an undeveloped prefrontal cortex. Smeared on the narrow country roads are mementos of tight turns and drunk drifting. A friend of mine once flipped a car by accidentally driving it up a steep and slippery grass berm. She was going slow enough that the worst of the damage was only to the side of the car that scraped the neighbors rock wall and no one got hurt. The incident also propelled her into delinquent fame. In the small community of high school students on Maui, being the girl who flipped a car will get you some invitations to parties at cliffside pool houses. Not too shabby a consequence for risking your life and the lives of others. She never drove drunk again of course, flipping a car would scare the shit out of anyone, but I remember my younger sister’s squad of giggling sixteen-year-old friends once recounting the story years later with giddy awe and smug teenage respect.

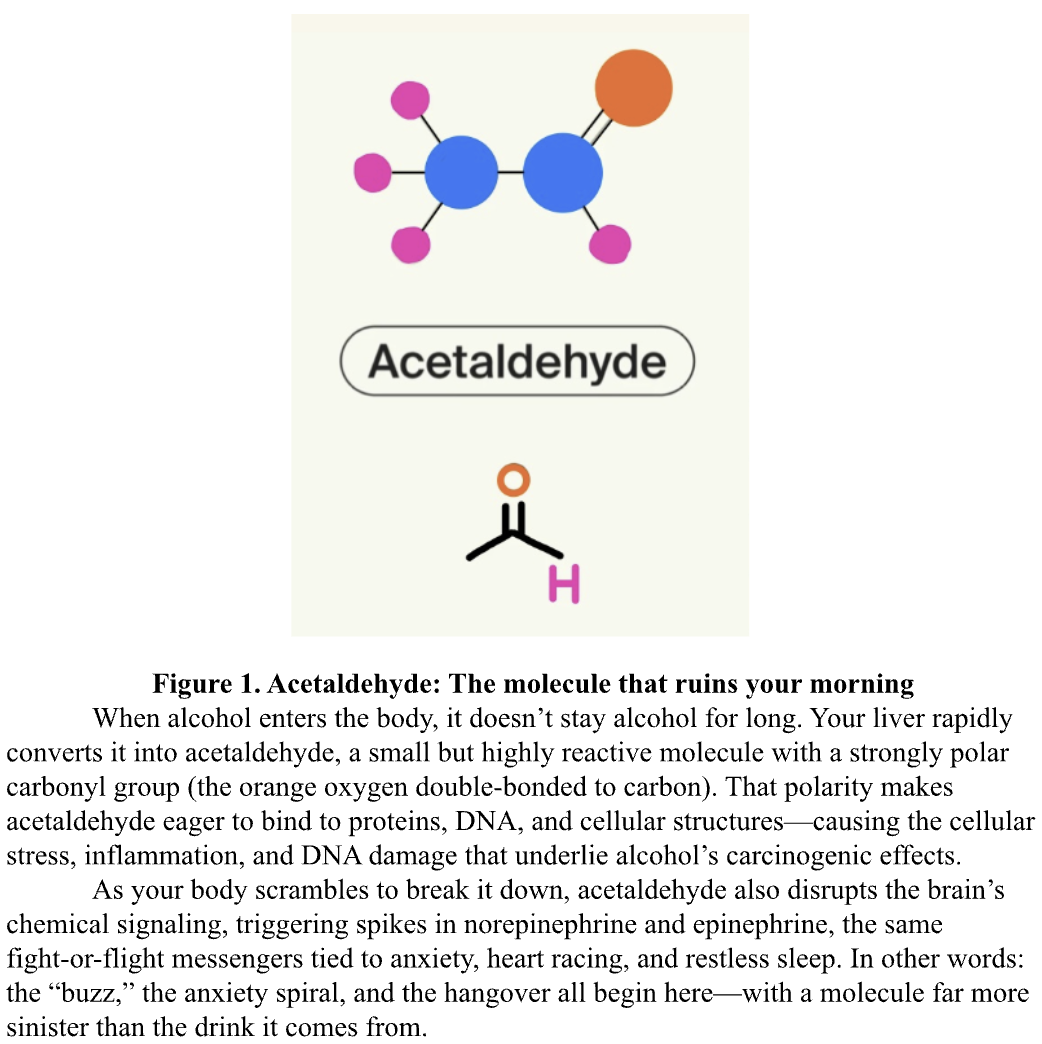

When you’re young, forbidden fruits are alluring simply because of the natural draw to have what one cannot have. Once the clock strikes your legal drinking age however, society’s misguided perception of drinking takes hold and perpetuates our collective drinking problem. Cigarettes had their moment of reckoning. Visceral depictions of discolored lungs and mandatory warnings on any purchase of tobacco don’t make it harder to find a pack of cigarettes, but succeed sometimes in dissuading the choice to keep buying that pack. Societal rebranding has not hampered smokers who smoke despite the cognitive dissonance between addiction and cancer. Arguably, the nicotine conversation shouldn’t be over, considering all the yummy vape flavors that target the young before their brains develop enough to understand the risks. Alcohol is still somehow at large, like a certain elected official whose undisputed criminal record logically should impact his political station, but it just doesn't seem to matter. An undercover poison. A wolf adorned in sheep's wool. A ticking bomb with a fancy label and an expensive-looking gold muselet. An unassuming liquid until it metabolizes into acetaldehyde (see Fig. 1), wreaking havoc on DNA and building up in the body. Different alcohol metabolism, diverse gut microphones, and the efficiency of the enzyme aldehyde dehydrogenase (ADL2) impact how effectively the body can break down acetaldehyde. I personally can’t tell how well my body breaks down the metabolic byproducts of alcohol, but I can tell when I have a hangover. A hangover is an indication that your body was not able to break down acetaldehyde quickly enough after its introduction into your system. Any hangovers we have woken up with in our lives are evidence that our bodies were overwhelmed by poison. It’s not like a long run that leaves you sore for a bit but ultimately results in better lung capacity and endurance. Drinking isn’t a sport. It will never make you stronger because it is poison. It will steal your gains after a workout, will dehydrate your body, and make you sleep poorly. We don’t talk enough about how bad alcohol is for us.

We talk about the liver. We talk about how strong and heroic our liver is after a Feisty Floko Friday. We might even talk about a headache and drink electrolytes to counteract our body’s desperate screams for help. But what about the complex signaling of our brains, working hard to regulate our moods, build our memories, and chemically orchestrate our decision making, derailed by even moderate alcohol consumption? I’m not arguing that we should consign ourselves to a life without ever having a drink again. I just feel that we should choose how much we want to drink taking into consideration the full scope of what we are doing to our bodies and our minds.