His name was Leroy

but in their language there was no equivalent.

They asked him its meaning and he told them:

Le Roi: the king

and so they called him Ons Koninkje: Our Little King

Where did you come from? they asked.

I was born in a castle in the sky

above the clouds, but below heaven

every day sunny and warm

every night cool and dark

like the desert.

What did you do for water?

Rivers of clouds flowed around the castle. We gathered them

up and squeezed them like marshmallows

& out came sweet nectar.

What did you do for food?

We collected stardust which fell on the castle grounds

& baked them into cakes.

What happened?

This in-between world turned unstable. Stardust began to fall heavier and of a different sort—metallic, inedible. The cloudwater grew polluted, its sweetness replaced by a dirty taste of rust. Or was it blood? The castle was under constant assault. Huge sections of the marble walls crumbled; falling debris kept injuring people. The inhabitants spent their time huddled inside, scared to venture out. Many died of starvation. The elders made the decision to forsake the castle, plunge into the world below, and take their chances with the earth-walkers.

“But you have no idea what’s below,” Leroy’s grandmother warned his parents. “There are stories that the people down there eat each other. How could you ever live among them? They sent up those terrible things in the sky which rain down on us.”

“We’re no safer here. If we stay, it’s certain death. Besides, what life is this for the child?” his father countered.

“Pshh! We’ve survived this long.” She refused to leave.

Leroy watched the exchange from behind a door, breathing as quietly as he could to keep from being noticed. Of course, he wanted to stay with his grandmother. While his parents spent their days working in the marble factory or rebuilding the walls with the rest of the adults, Leroy’s grandmother watched him. They played Mahjong together with marble chips. And, even though she was old and had pain in her back, she indulged his games of hiding, covering her eyes, counting to 10 and then bending over to look inside cupboards and around corners, or stretching to see if he had folded himself onto the top shelf of a closet. She taught him how to bake cloud cakes and gave him cookies made from distilled cloudstuff which his parents never let him have for fear of spoiling him.

And the stories. His grandmother often let Leroy stay up late, talking to him about grownfolk things, like the history of their people, how she and his grandfather first met, and the previous wars which their people had won. This wasn’t the first and surely it wouldn’t be the last. Their people survived. They always survived, she wanted him to know. He listened, often falling asleep on the rug at her feet.

Their games were often interrupted by aerial bombs or the shaking of the castle as it returned fire. In these instances, his grandmother would take him to the corner of the house and hold him tight until it all passed.

The night they were to depart, Leroy huddled in the same corner. “I’m not going,” he cried. He hoped his parents would relent and leave him to stay with his grandmother. Leroy’s parents couldn’t convince him and his father didn’t want to force him. They pleaded with his grandmother to reason with him. The castle was crumbling and would, any day now, collapse.

Is this what she wanted—for her only grandchild to be buried under the weight of her own stubbornness?

No, of course not. Leroy’s grandmother took a big breath and went to him. She crouched on her bad knees and took Leroy’s hand. She whispered in his ear. Leroy kissed her and gripped her for a moment. He wiped his eyes and joined his parents.

“Are you coming?”

“No, honey. I have a longer past than I do a future. You all have a hard road ahead of you and it’d be even harder with me. You don’t need to worry about me. What did I tell you our people always do?”

“Survive.”

“Exactly.”

Leroy asked his grandmother how he would hear from her—how would she let him know that she was OK? She said that she would send messenger birds when she could, when it was safe for them to travel and when she was sure they would reach him.

———

One by one, his people stood at the edge of the sky,

hungry and afraid. And they jumped through the clouds.

Some, however, remained—

like his grandmother not everyone could (or would)

throw themselves into the unknown.

And so it was that families like Leroy’s were split asunder

during what his people would call the

Great Descent.

———

As he told his story, Leroy watched his audience closely, noting where they gasped in shock or amazement, when they released involuntary sighs or drifted off during the less captivating parts. He modulated his voice, aiming to maximise their young attention spans.

The other children, spellbound by these tales on the playground, went home and told their parents of this magical boy. Sometimes they embellished the story, other times they left things out. Of course, their parents thought this was all ridiculous. They pointed to the map of the country where Leroy came from, explained that he and his family arrived by aeroplane. The parents gave the boy and his kind a name which the children found hard to pronounce. Their parents spoke of things like protectorates, colonies, independence, and shared governments, none of which the children understood or were particularly interested in. They did not like this story from their parents. Not at all. They preferred their little king’s version of events.

Not all of the children, however, were convinced.

One such child was Thijs, an older boy at the primary school, whose nature was to be skeptical to the point of heresy. At the dinner table he would follow his parents’ conversation and nod with a solemnity belying his actual age. If his father made an assertion which Thijs doubted or (and this was more likely) an assertion which Thijs knew to be categorically incorrect, he would interject: “But, dear papa, you are mistaken.” Thijs was the first child in his school to stop believing in Sinterklaas.

Before Leroy, it was Thijs who had commanded the attention of the other children, regaling them with demonstrations of science, like his award-winning volcano which mimicked the smell of burning sulphur with eggs and vinegar. Since Leroy had arrived, however, the children (and even the teachers) had lost interest in Thijs. He watched irate as the rest of the school fawned over their newest addition. Even at Thijs’ home, Leroy and his family were stars.

“I ran into one of them at the grocery store,” Thijs’ mother said at dinner one night, drinking a glass of wine.

“Oh?” His father’s interest piqued enough to make him look up from the newspaper.

“Fascinating story. Tragic, actually,” she said.

“I can imagine.”

“We have one in our class. He’s always telling lies, stupid made up stories about where he came from that don’t make any sense, like out of a fairytale,” interrupted Thijs.

“It’s probably a coping mechanism. I’m sure he’s just traumatised,” said his mother.

“He’s full of shit.”

“Thijs Bartolemeus Mattias,” she said, employing his full Catholic name to effect. “I don’t care what you think, you be nice to that poor child. We should invite him and his parents over for dinner.”

“God, please no!”

“Honey, what a marvellous idea. We can introduce them to some of our food and way of life.” Thijs’ mother instructed Thijs to invite Leroy and his parents to dinner.

It was settled. The next day at recess, Thijs walked over to Leroy and with reluctance extended the invitation.

“Should we bring anything?” asked Leroy.

“Ugh. I don’t care. Just be there at six.”

Leroy beamed for the rest of the day. At home, he didn’t relay the invitation to his parents. Though he had never met Thijs’ family or seen his house, he knew from the boy’s clothes and from his shiny new bike that he was rich. He didn’t want Thijs to meet his parents, to see how they dressed, to have another weapon to use against him in their playground war.

A week later, Thijs, his parents, and Leroy sat around the table.

“My parents send their apologies, they have to work tonight.”

“That’s OK. We can do this again another time, with them, Thijs’ mother offered brightly. “Did you like the food?”

“It was all delicious. They’ll be sad they missed it. Next time you can come to ours. We can cook for you,” Leroy offered.

“Your food has too much spice for me,” said Thijs’ father. Leroy didn’t mention how the dishes had been either flavourless or over-salted.

“Had you ever had potatoes before, Leroy?” asked the mother.

“Once or twice,” he replied, failing to mention they ate them almost daily. In fact, the potato originated from his home country and had been, through a circuitous and bloody route, introduced here. Leroy’s father often ranted about how everything in this “Old World” was stolen from the New. Though, of course, that wasn’t something to be discussed now.

“Why don’t you ask him about where he’s from,” Thijs said loudly.

Everyone looked at Leroy. Unsure of what this audience required, he tried to read them. He knew where Thijs stood, but his parents were different, unfamiliar. Their faces, set and closed, revealed nothing. Leroy moved his mouth to speak, but a cough escaped instead.

“Oh, honey. You don’t have to talk about it. Not if you don’t want to. Here, have some more cake,” said Thijs' mother, almost in tears.

“Thijs, why don’t you take Leroy upstairs and play for a bit,” commanded his father. Thijs groaned in response. “And remember what I told you.”

Thijs walked begrudgingly upstairs with Leroy following. The house was bigger than it had looked from the outside. The dining room opened into a large living room, at the end of which loomed a staircase leading to the second floor. Leroy and his parents lived closer to the town centre in an apartment building with narrow, steep stairs.

It was impossible to pass someone on those stairs, meaning if two people were walking in the opposite direction, one had to retreat to the landing to give way to the other. Still, Leroy loved playing in the building’s angles and corners. He imagined the small crevices were secret passageways to unknown worlds waiting for his discovery. His parents spent their days working at a ship factory and came home tired, listless ,and silent. The move had been difficult for them, especially his mother whom he often heard crying late at night.

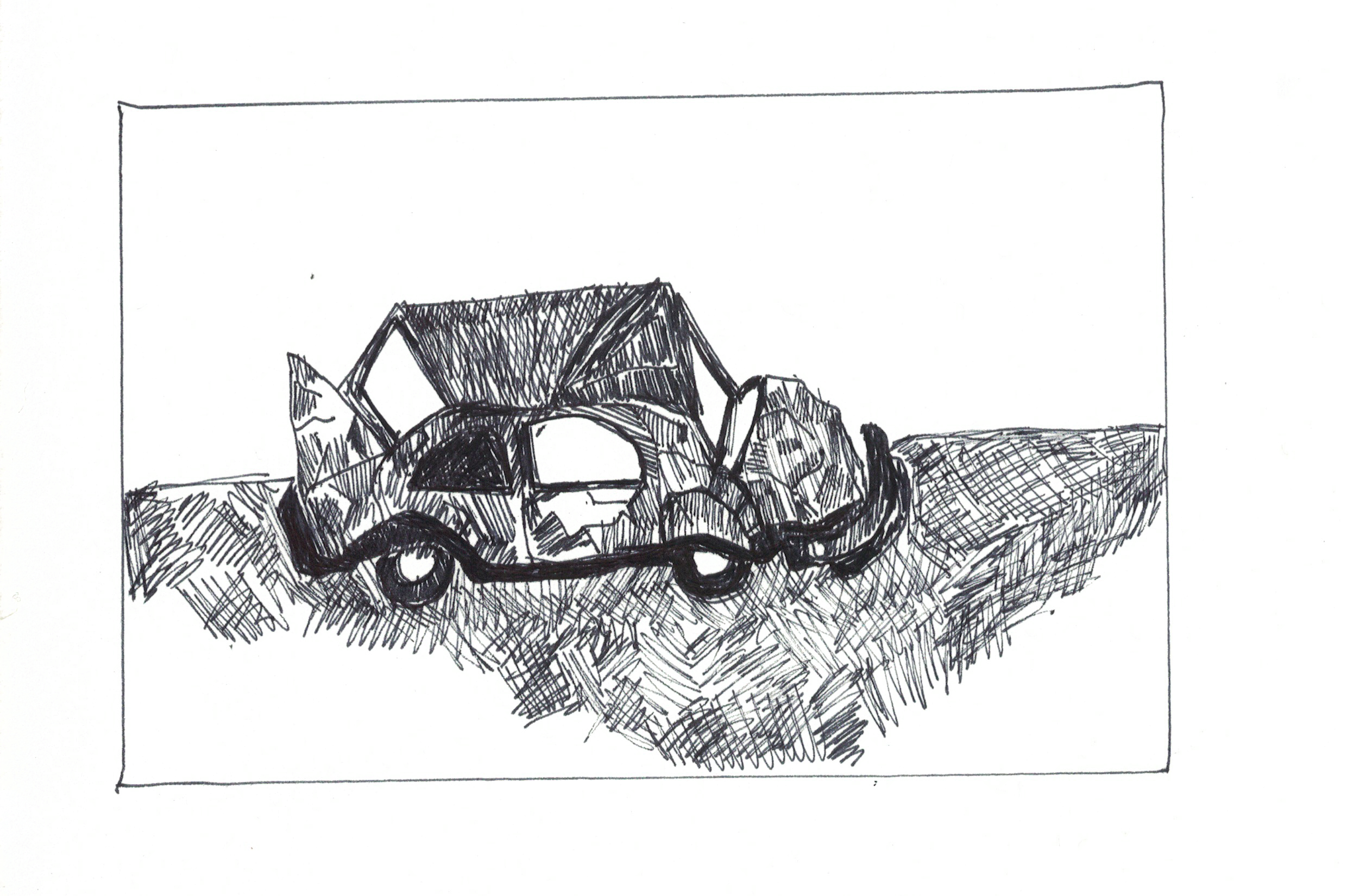

Upstairs, Thijs' room was as large as Leroy’s family’s entire apartment. Thijs showed Leroy his model train and car racing set. “Here,” Thijs said as he thrust a broken car into Leroy’s hand.

“What’s this?”

“A toy. Jesus, don’t you know anything? My mother said I had to give you something. She didn’t say it had to be nice.”

“What happened to it?”

“My dad ran over it with his car.”

“Sure, whatever. Thanks,” Leroy said, pocketing the car. He surveyed the piles of clothes on the floor, the books haphazardly stacked in a corner, the dusty stereo and the walls covered with posters of pop stars and comic book heroes. “You know, I don’t get why you’re so miserable if you have all this stuff,” he said before turning and running down the stairs.

It was getting late and Leroy had to get back to his parents. He had told them he was working on school project with a classmate. Leroy thanked his hosts for their hospitality, kissing Thijs' mother three times and offering his father a firm handshake.

On the way home, Leroy decided to take a longer route so he could cycle next to a canal—he could always say he got lost if his parents asked why he was late. The neighbourhood was relaxed at this twilight hour. Leroy’s father complained that it was too quiet in this country. But Leroy didn’t agree. There were sounds, but of a different sort than those from home—cicadas, the buzz of lawnmowers, echoes of clanking dinner dishes, slow and easy radio music. And the birds! Never had he seen so many and such variety: hawfinches, black-tailed godwits, greedy herring gulls, and his favourites—the herons. He memorised the charts at school and did his own reading on their eating, mating, and migratory habits.

Large elms stood tall and straight on the canal banks, as if standing in line at the store; their branches performed a languid dance over the wide waterway. In the distance Leroy could see cranes adding new buildings to the skyline. He learned at school that the entire city had been destroyed during a war that had ripped the continent apart, but he couldn’t believe it, not from how it looked now.

He heard the sound of an approaching bicycle behind him. He moved to the left to let the rider pass. The rider rang the bell furiously, nonetheless.

“That’s not how it works!” the cyclist yelled.

Ting-ting-ting!

Leroy veered to right to let the bike pass, but the cyclist kept ringing the bell. He looked leftward and back to see what was happening. A boy a few years older than Thijs but with bright red hair gave him the middle finger. The cyclist grinned, nasty and lupine. Leroy turned forward to watch the road. The front wheel of the cyclist’s bike grazed against Leroy’s leg and then braked, causing Leroy to swerve again. The cyclist sped up and cut him off. Leroy braked hard and lost control of the bike, falling over onto the path. A crow watched from the top of a street lamp, blinked its eyes once the scene was over, and flew away.

Leroy’s pants were ripped, his knees were skinned, and his wrist was twisted. Stunned he looked ahead at the cyclist, who turned around to let out a red-faced, throaty laugh. “Go back to your own country if you can’t figure out how to ride a bike!”

Leroy told his parents what happened later that night. His father smashed a plate and stormed off to the small balcony to smoke a cigarette.

The next week, Leroy was in the middle of one his lunchtime sessions with an audience of rapt classmates when Thijs came up to him.

“Stop this ridiculousness,” Thijs demanded. Fists clenched like miniature cannons ready to fire, Thijs towered over Leroy and in his rage looked ready to strike.

“What do you want?”

“Admit you’re lying.”

“But I’m not.”

“He’s not!” the other children protested on Leroy’s behalf.

“Prove it then. Every event has some proof it happened.”

Leroy turned his back to Thijs as he addressed the gathered group. During the Great Descent not everyone landed safely, he explained. In fact, many were hurt, including Leroy. As his family jumped, Leroy tried to hold his father’s hand tight, but their grip loosened and Leroy fell hard to the ground. He pulled up the leg of his pants to show the scratches. “And my grandmother gave me this before I left. It was crushed when I fell.” He produced the toy car Thijs had given him.

“I gave him that car! He got it at my house,” Thijs said from behind himself. But he had already lost—the other children were disinterested in his protestations. They pulled Leroy over to them and walked him to a picnic table. Before him they had laid out what they had been able to spare from their lunches or surreptitiously steal from home. Leroy surveyed the array of orange juice, chocolate chip cookies, cheese sandwiches, and apples laid out before him—stacks of food piled higher than he was tall—and it was thus, when he realised where a king’s true power lay.

As they sat, a little bearded reedling hopped on the pavement near the picnic tables. Leroy recalled how he had told the other children of his grandmother languishing on the other side of the atmosphere with no way to reach him except through the deployment of trained birds.

He watched the reedling and threw a bit of bread to it. It sang something in response. A teacher gathered the kids to go back into class. The bird flew up to the picnic table and hopped toward Leroy. It continued chirping, but now faster and with determination. It chirped and chirped, straining its voice to reach a louder volume. Leroy tossed more bread, but it ignored the food and continued toward him.

“Now, please, Leroy,” called the teacher. Leroy stood up and headed towards the door.

The bird remained—its chirps now a histrionic screeching. It jumped furiously up and down on the table.

“You shouldn’t feed the birds,” the teacher admonished.

Leroy looked back at the bird jumping furiously, beside itself, almost screaming—it was as if its or someone else’s life depended on delivering message which he didn’t, couldn’t understand.

Written by Lloyd Miner

Art by Dakota Peterson

Lloyd Miner is a writer currently living in Amsterdam. Originally from the U.S., he has degree in Film Studies from Columbia University. He writes prose and poetry and sometimes a combination of the two.