At the intersection of science and religion

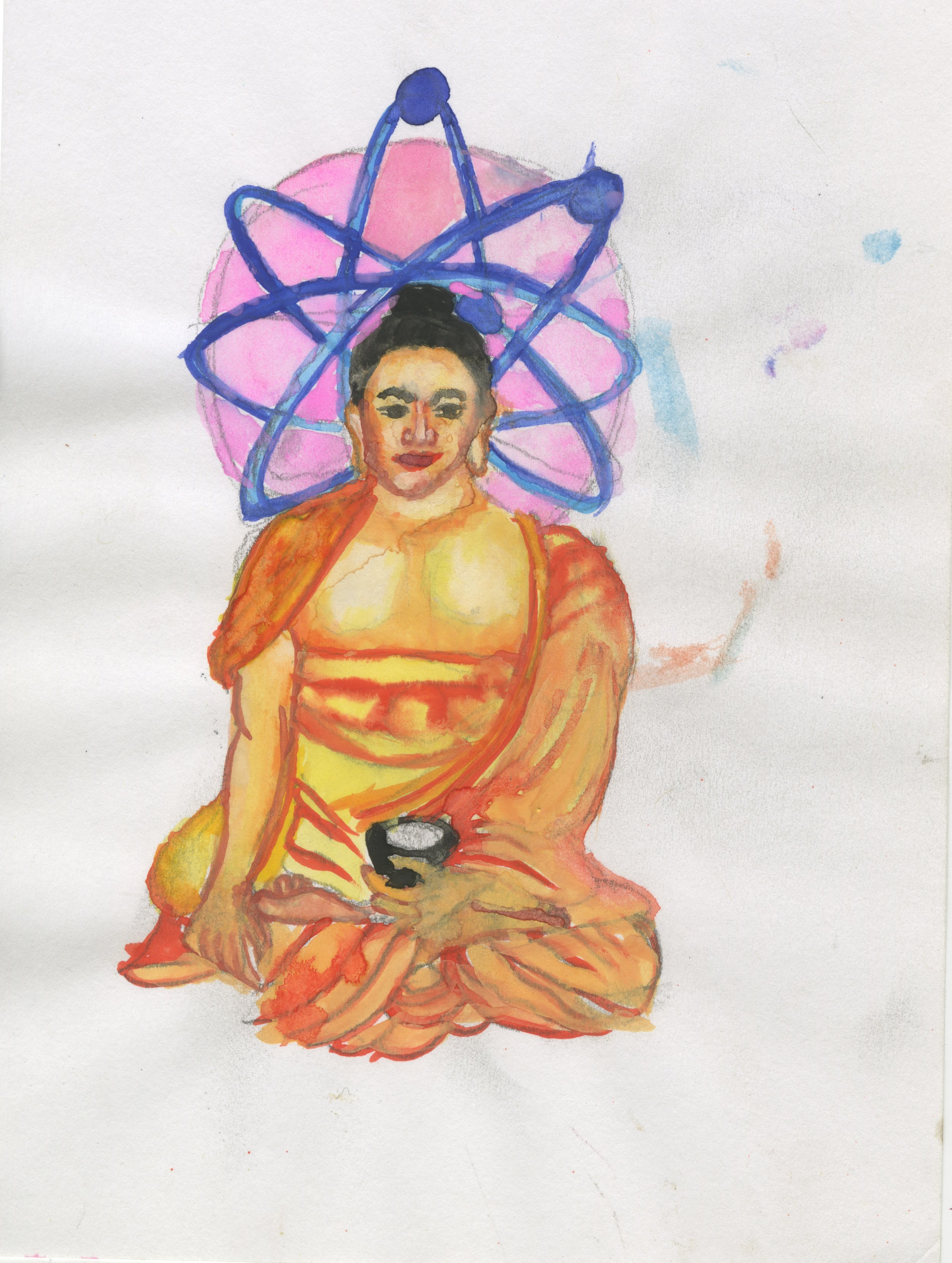

by Isaac Rubinstein, illustration by Abi Censky

I was sitting with my dad, struggling with middle school math homework, when a wave crashed over me. I had an epiphany. I felt the world blossom within me as I learned something new. The revelation provoked me and gave me a taste of things to come. Years later, I can’t remember exactly what the hell I got so excited about, but the feeling stuck with me. I felt myself become a different person. I became self-assured in my way of seeing the world.

This awakening began to fade into memory as new became old, and the once-revelatory knowledge loosened its grip on me. This insight began as an anomaly in my everyday experience, but the knowledge came to be taken for granted and I, for a time, lost the thrill of the intellectual chase. I became complacent and stuck as evidence started to pile up. My worldview became outdated and I began to notice things that didn’t fit. The complicating and confounding nature of these observations threw me into doubt, but doubt is where miracles happen.

Though I didn’t know it at the time, there would be many more epiphanies to follow. Maybe it was my last epiphany concerning the workings of algebra, but I continue to experience sudden, visceral moments of insight. However, I know I will never have a final epiphany in which I come to a complete understanding of the world. Humans create unanswerable questions, questions that have an infinite number of answers. This not-knowing is the spice of life.

There is always a seed of doubt in each revelation that propels further insight. I may feel stagnant in between these experiences of knowledge acquisition, but I am actually working my hardest in these moments of stuckness. I inherit freedom from being stuck.

“Quantum mechanics reconfigures how we view the world into a map of shifting probabilities. it states that prior to the measurement of the subatomic particle, there are only probabilities—uncertainties—considering the characteristics of the subatomic particle”

When we are stuck we are creative through necessity. Epiphanies are moving, but the hard work of being stuck and striving is of vital importance to us as individuals and as a species. In our modern age, we look to science for “a language to describe and understand the world,” says Shane Burns, a Colorado College physics professor. He was a part of the team that won the 2011 Nobel Prize in Physics for a discovery concerning the accelerating expansion of the universe. Burns helped me understand how he, as a practicing scientist, thinks about his work.

Burns spoke with me for a few minutes—with and without his science cap—only taking it off to say: “What science does, is that it makes models that mimic the way the world works. The theories themselves are creations of the human mind.”

I didn’t see Burns’ need to take off his science cap to say this, as I thought science’s inter-subjective nature was a given. Burns critiqued objectivist views of science and in doing so enriched my understanding of the practice.

“Science really never proves anything. Science is a good way of weeding out theories that don’t work.”

I came to understand science as a creative process in which the models made have to be consistent with observation and have to predict results that could be tested by observation. From observations and back again, science finds itself in an infinite loop of the creation of models that will be added on to, complicated or disproven in the future. Science is already partly correct and partly wrong. “Science is always provisional,” Burns concludes. Science’s ability to be wrong makes it flexible, which has allowed us to grow and learn at an incredible rate over the past millennia. Science has the ability to contradict itself retrospectively. As new data start to contradict old models, old ways of thinking are complicated and declared incorrect by the scientific community. The constantly changing, uncertain, chaotic world of science is exemplified in quantum mechanics.

Physics has undergone major upheaval in recent scientific memory, and quantum mechanics is to blame for much of this shake-up. I will neither explain the last 100 years of the history of physics, nor explain the math behind the conclusions of quantum mechanics, of which I know very little. What I can do is provide a cursory theoretical understanding of quantum mechanics to see why quantum mechanics challenges classical physics and anyone who believes in science’s understanding of the world.

Quantum mechanics reconfigures how we view the world into a map of shifting probabilities. It states that prior to the measurement of the subatomic particle, there are only probabilities—uncertainties—considering the characteristics of the subatomic particle, namely: location, spin, particle and wave. The act of measurement makes the unknowable knowable, but it is only a fleeting moment of clarification in a world of uncertainties. Quantum mechanics sees measurement as the subject affecting the object while the subject simultaneously comes to know the object. So the subject never knows the subject on its own, or in itself—we always know the object in relation to us.

“Entanglement” in quantum mechanics states that a subatomic particle cannot be described independently of others. When particles are entangled with one another but separated in space, there is an immaterial bond that makes the particles act similarly. If we affect one, the other one is also affected. Particles do not act independently of one another. They are in a web of entanglements that create a relatively stable reality from a fundamentally chaotic one.

It struck me that Buddhist thought reflects this understanding of the world. Both identify a groundless and uncertain reality, which is still able to create meaning and stability in a chaotic world.

Just as entanglement theorizes the connectedness of things to each other, the Buddhist teaching of “dependent arising” states that all things are dependent on other things. “Dependent arising” in Buddhism is often paired with the Buddhist understanding of emptiness as the foundationlessness of reality. Emptiness as the ultimate truth or reality in Buddhism is comparable to the chaos described by quantum mechanics because both view the world as lacking a foundation or any inherent quality. The lack of an essence can throw us into a nihilistic spiral, or it can allow our creativity to fill the world with meaning.

To think more about how science and Buddhism intersect I talked to David Gardiner, the well-loved CC Buddhism professor. Even though we at CC pride ourselves on our open minds and hearts, we too still have dogmatic tendencies. As Gardiner says, “those that say we shouldn’t have dogmas in religious or scientific communities are still working through those natural dogmatic tendencies. There is something in the brain of many people that finds it easier to hold onto a truth because it gives us an anchor for identity.”

To avoid dogmatism, Buddhism uses the word shraddha, which translates into faith or trustful-confidence. The difference between blind faith and the trustful confidence is doubt. In trustful confidence, there is still the seed of doubt. In blind faith, the land is inhospitable for a seed of doubt to take root.

Doubt is the creative spark. Doubt is epiphany and doubt is in our blood. Doubt exists because at some times, we have gone through a private, emotional epiphany or a cultural, scientific, religious epiphany in which we proved ourselves wrong and contradicted ourselves to grow. With doubt we are able to look at texts with critical intensity. Because of doubt we devise a more efficient way. Doubt makes us vulnerable. We know that getting close is a risk. Doubt is why we are vulnerable and not simply open. And doubt owes its existence to our ability to be wrong. We try things not to succeed, but to fail. Our intuition tells us we want to succeed, but failing is learning. Failing is the being stuck that precipitates and necessitates growth.

Gardiner, a practicing Buddhist, asserted that “chaos does not mean meaninglessness, we still have the capacity to make meaning within the chaos.” Quantum mechanics asks the scientific community to grapple with an uncertain, chaotic, foundationless world, while Buddhism has been asking us to do this for centuries. The scientific method and Buddhism both allow us to create and destroy our own truths, so long as we are honest to our observations.