Natural birth and obstetric violence

by Holly Pretsky

My first day in Valparaíso, Chile I passed this poster on the outside of a building while walking to school. It showed a pregnant woman, a chain extending from her nipple to the earth that is her womb, a colonizer on her shoulder, a dollar bill plastered to her breast. “Nuestro mundo está embarazada con otro.” Our world is pregnant with another. I haven’t been able to rid myself of that image.

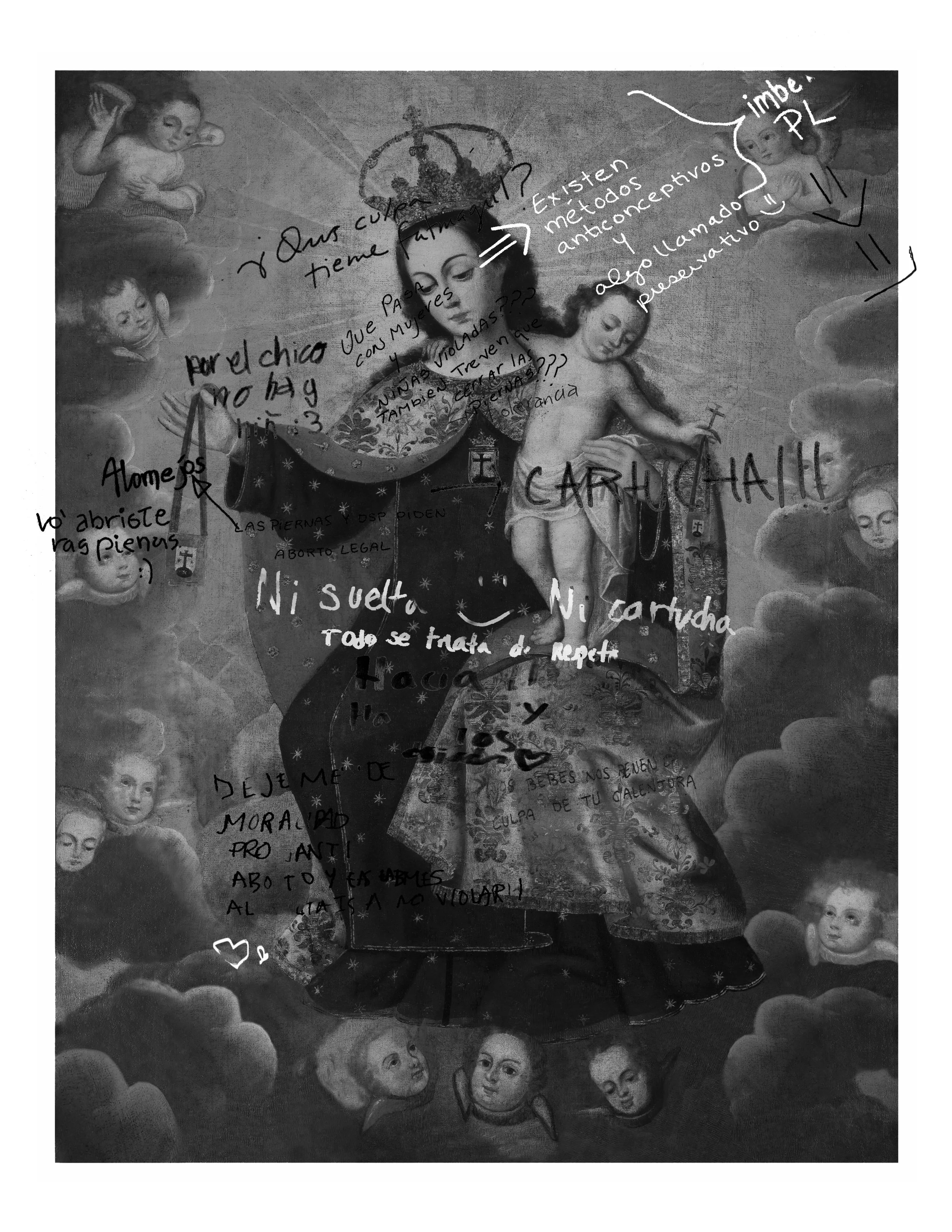

Chile is obsessed with pregnancy. The Virgin Mary, the archetype of baffling fertility in Western culture, presides in some form or another over almost every city, town and village in the country. “Legend has it that the Virgen de la Merced appeared in the river here in this village,” a vineyard worker in Isla Maipu relates as we tour the vineyard chapel. “She’s been our protector ever since.” It’s a rigidly Catholic country where abortion is totally illegal, including in cases of rape, incest and when a woman’s life is in danger. In 1989, the government of Augusto Pinochet, a military dictator who ruled Chile from 1973 to 1990, prohibited abortion and made it punishable by up to five years in prison. Engraved in stone on a wall outside La Catedral de Valparaíso is a tribute giving voice to aborted children. “They tore us apart,” it says, “they strangled us, they poisoned us with the indifference of an executioner. For our death, they pay money.”

When we talk about feminism in the United States, when we talk about “A Woman’s Right to Choose,” we’re frequently talking about abortion: access, affordability, dignity. To be a feminist is—at least partially—to support a woman’s right to terminate a pregnancy if she elects to do so, to recognize that pregnancy (and subsequent motherhood) is not an obligation, that a woman is not an incubator. But assuming a woman wants to be pregnant, there are other choices that manifest, about which feminism, in my experience, has been somewhat less ardent. What about a woman’s right to choose how she wants to go about her pregnancy? What about her right to choose the way she wants to give birth?

In a country where abortion is illegal, giving birth is required. In a country where giving birth is required, pregnancy has become somewhat of a business. According to Carlos Artemtchonque, a Brazilian gynecologist who has worked in a public hospital in Chile for the past eleven years, Chile has one of the highest rates of Cesarean sections in the world. According to an article in La Tercera, a Chilean newspaper based in Santiago, 40.4 percent of births in public hospitals, and close to 70 percent of private hospital births, in 2013 in Chile were Cesarean section surgeries. In the last 50 years, Chile has made changes in public health policies surrounding birth, requiring more tests and medical exams, significantly lowering the death rate for infants before, during and after birth. The Chilean government actually encourages vaginal birth, which is partially why Cesarean sections occur less in public hospitals. They continue to be so popular, Artemtchonque says, because they usually take less than a half hour, they are painless, they don’t alter the woman’s body (think vaginal tearing) and they can be scheduled beforehand. Women are frequently pressured by private gynecologists into a Cesarean section, according to Artemtchonque, because the process is controllable, and there is less risk of complication during the actual surgery. In Chile, gynecologists are sued more frequently than any other type of health professional. According to Artemchonque, this pressure leads them to encourage a woman into a medicated or surgical birth that is completely under their control.

While Artemchonque is concerned about the rise in Cesarean sections, he has no qualms when it comes to reducing labor pains. He recommends a vaginal birth, usually, and supports a woman’s choice to use some form of anesthesia. In his mind, no woman should have to suffer giving birth. With modern technology, it isn’t necessary. Artemchonque has been a gynecologist for more than 30 years, in two different countries. “I’m a feminist,” he tells me. “Here in Chile they are very machistas. It’s a reality here that the husband doesn’t want for his wife to spend much time out of the house.”

One way of communicating “to give birth” in Spanish, albeit a bit formal, is dar la luz, to give light. In the midst of this trend toward medicated, surgical birth, a small but tenacious resistance is taking root. Despite the challenges they face in a country where birth is so heavily supervised, more and more Chilean women are electing to have a natural birth within their own home. “The woman cultivates an awareness of her body, eating well, doing exercises to get to know her vagina, to know her uterus, to understand how it works,” Daniela Rojo Robles, a Chilean midwife with wild curly hair and a septum piercing, tells me. Rojo Robles studied obstetrics at the University of Valparaíso and now works to guide women through natural birth in their homes.

According to Daniela, this is a new movement, a product of the last four years or so. “The majority of women prefer to use anesthesia. But with homebirth, women can really know what they are capable of, understand what the body is capable of enduring. Sometimes labor can last three days, after which the woman is exhausted, but has the satisfaction that she was able to endure labor without anesthesia.” I ask Dr. Artemchonque about home birth. He doesn’t recommend it, believing only hospitals are equipped to respond to the various risks that come with giving birth. “Generally, birth is simple,” he says, “but when it’s not, the complications can be very grave.”

Daniela invited me to a meeting of her feminist group “Círculo de Lilith” one Thursday night in the hills of Valparaíso. The topic: obstetric violence. One woman gave testimony about her C-section, describing how the doctors barely talked to her, choosing instead to discuss a recent football match as they went about preparing her for the surgery. After the baby was born, she had to wait four hours to hold it. A YouTube search will bring up many more stories like this one, not just concerning Cesarean sections, but hospital birth in general. Women feel exposed, vulnerable and unimportant while going through a process during which they should feel indomitable.

“In public hospitals, there are a lot of people examining: there’s the midwife, there’s the doctor, there’s students, so the woman feels very observed,” Daniela tells me. “When you go to the hospital, you have to be naked there for a while so that different people can put their hands in your vagina. Obviously this produces a rejection response in the woman. I don’t think anyone likes that.” This isn’t just an issue of comfort. The feeling of exposure and undue stress has chemical consequences. Daniela describes oxytocin, a hormone released during labor, that eventually helps the woman to breastfeed. When she is under a lot of stress, levels of oxytocin are affected, which causes complications with lactation down the road.

While in the south of Chile, I had the opportunity to speak with a Mapuche woman, Benita Pengilef, about her experience giving birth in her home. The Mapuche are the indigenous group that once occupied most of modern day Chile. Due to violent colonization that continues today, now mostly live further south, below the Bío Bío River, but some have returned in great numbers to Santiago. We sit down at the giant handmade dining table in her family home. Her husband, Alejandro, is the lonko, or leader of their community close to Curarrehue. Señora Benita has given birth to six children, four girls and two boys, all in her own home. She was accompanied by a puñuñalchefe, a Mapuche ritual midwife, for each birth. The Mapuche believe that the puñuñalchefes are endowed by the gods with the ability to help women give birth.

“God gives them the intelligence to do it, no more.” Puñuñalchefes would spend days with the mother in labor, guiding her through rituals, providing herbs to calm her and giving her massages. I ask Señora Benita if there is a puñuñalchefe in the community today. Her face becomes stony. There is not. The puñuñalchefes were threatened and even killed under Pinochet’s dictatorship, and now it is illegal to have a baby outside the hospital. I find that idea somewhat appalling. “But how could they know?” I asked, “How could they know whether people are pregnant at all?” Every year, according to Señora Benita, government officials pass through all of the villages to conduct a census, and women are required by law to disclose their pregnancies. Señora Benita believes that the government forces the women in her community to give birth in the hospital as a strategy for control. The women have to pay for hospital services. She looks at me frankly, not breaking eye contact. “It’s a government law to make money, no more.”

I asked Daniela if, given the requirements for testing and exams, there are laws in Chile that specifically prohibit natural birth. “The government doesn’t entertain the possibility of giving birth at home,” she responds, “There’s a legal void.” Although homebirth is not specifically prohibited, women who want to do it have to be careful who they talk to. “I’ll give you an example,” Daniela says, “There’s a woman, Anna, who wants to give birth at home, and Anna tells her mother, who disagrees with her decision. Her mother could then go to the closest doctor’s office and report that her daughter wants to give birth at home. And then social agents can go to her house, do an investigation and ultimately take the child. Because she wanted to give birth at home, she won’t be a good mother.” It’s starting to seem ironic to me, that women who insist on giving birth naturally, who refuse to surrender this process to an institution, are the ones who risk losing the right of motherhood. “They do everything in contradiction to what society demands. They are doubted women, doubted in the sense that society criticizes them for not being worried about the child. But all of the women I have met, all they want is for the baby to be born with all the love possible. They want to prepare physically, prepare mentally, prepare spiritually to give birth.”

Chile may be rigid when it comes to so many things, but I’ve found its people to be indefatigable in their pursuit of change. During the Círculo de Lilith meeting, we sit in a circle around a coffee table laden with cake, dried fruit, bread, tomatoes, avocado and tea. We’re discussing an upcoming workshop the Lilith women will present on natural birth, abortion (myths and fears and how to get one) and obstetric violence. The women divide up tasks, each responsible for teaching one or two topics. There’s a moment of quiet when no one volunteers, and one of the women nods at my friend and me. “What about you two?” She asks, “You in?”

A memorial for aborted children on a wall outside the La Catedral de Valparaíso

The engraved text reads:

"To the memory of children killed before birth. They killed us because they said we were too much, like Herod thought that Jesus was excess. No one could defend us. Everything was in the silence of our mother's wombs. They tore us apart, they strangled us, they poisoned us with the coldness of an executioner. For our death, they paid money. They threw in the trash pieces of our little bodies. They burned us in an incinerator."