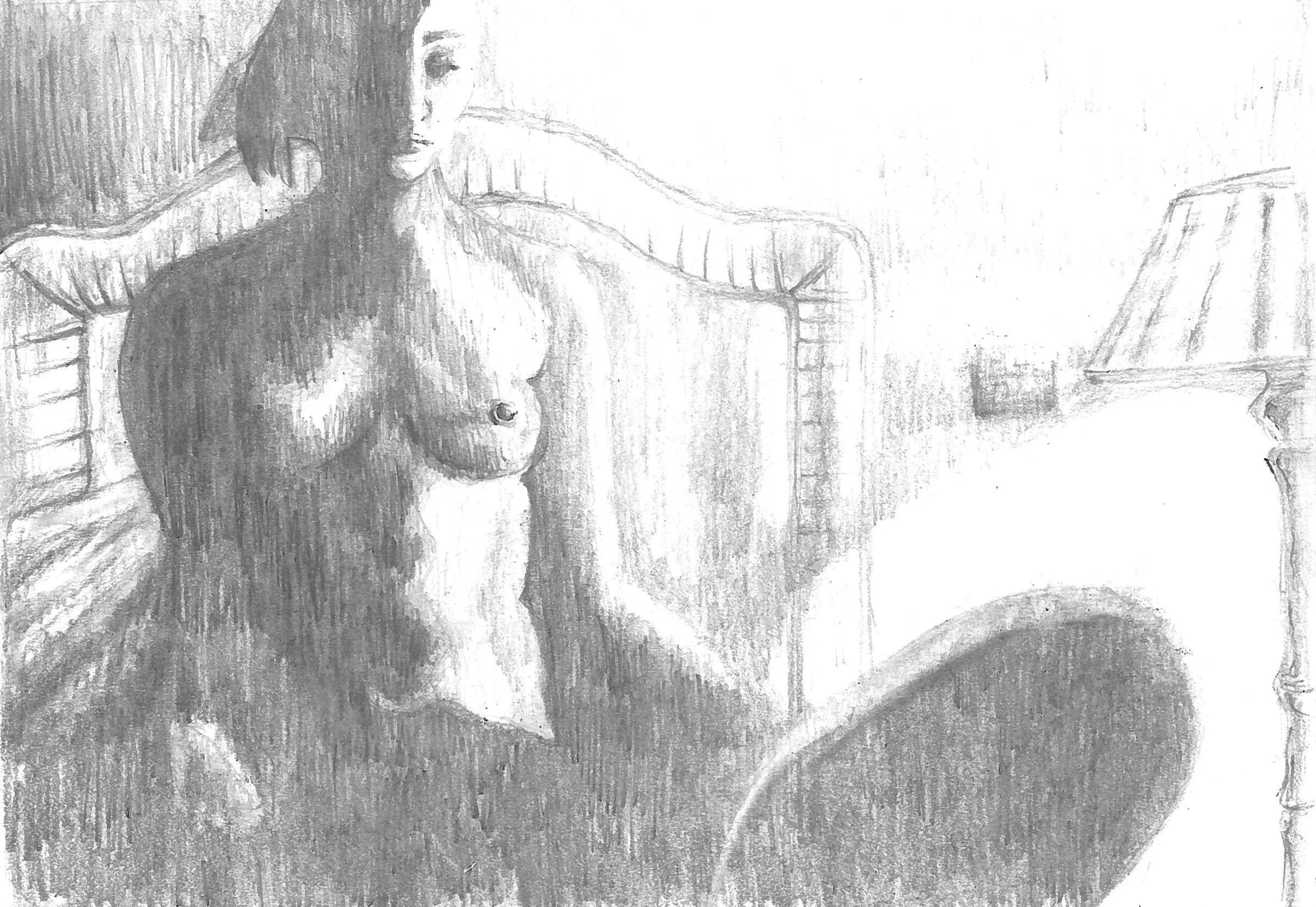

by Maggie O'Brien; illustration by Hannah Seabright

She has long, silver hair. It’s so long it whispers against the ground and it’s so shiny you can see your reflection in it. She has green eyes like leaves and wears a lemon sweater with buttons. She’s strong, and she likes apple cinnamon muffins.

Or maybe her hair spirals from her head like a halo. She’s all curves and confidence. She struts down the street in a crisp pantsuit and smiles at everyone she passes. She’s a woman who knows where she’s going. She’s a woman who glows.

Or maybe she’s everything else: short, round, tall, pink hair, dark skin, pale skin, freckles like constellations, small breasts, breasts that wiggle, naked, colorfully clothed, a single mother, never a mother, a businesswoman, a teacher. Maybe she’s in love: with herself and with the world.

What if God was a woman?

The Abrahamic religions, specifically Christianity, are gendered. The Bible reverts to the male pronouns He/Him/His when referencing God. In the Book of Genesis, we read: “God created mankind in his own image.” The Bible, the most read book in the entire world, set a precedent for other important documents to use male pronouns and male-centric terminology. In the Declaration of Independence, our Founding Fathers wrote: “All men are created equal.” In the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights, written in 1948: “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.” Although these were written as secular documents, they reflect the legacy of Christianity—the most practiced religion in the United States—and its characteristics ingrained within our society. Even our national anthem and Constitution reference God.

This language is limiting. Words such as “men,” “brotherhood,” and “mankind” fail to represent the entire population. Even the words “women” and “female” can be deconstructed as sexist. These documents created to grant equality—if interpreted literally—only grant equality to men. People are raised, all over the world, believing that the Head of the Universe, the Creator, the King of the Sky—is a man. Because of this, religion sanctifies and perpetuates patriarchal values within our society.

“He walked her down the aisle of their sanctuary, right to the base of the stairs and told her a story: Eve, the very first woman of the Bible, caused man to fall.”

Rev. Dr. Ahriana Platten, the minister of Unity Spiritual Center in Colorado Springs, was twelve years old when she discovered she couldn’t be an altar girl. When she asked a priest why, he walked her down the aisle of their sanctuary, right to the base of the stairs and told her a story: Eve, the very first woman of the Bible, caused man to fall. She picked an apple from the tree in the Garden of Eden and ate it. The priest told her that because of Eve’s sin, women could not serve God. Ahriana could not be an altar girl. Nor, he explained, would she ever be allowed on the altar unless she “was getting married or if it was [her] turn to clean.” Ahriana went home and told her mom she wasn’t Catholic anymore.

Ahriana’s experience is not isolated—there are many other religious institutions that regard gender within the Bible seriously and literally. Colorado Springs is a breeding ground for these groups, such as the evangelical organization called Focus on the Family, which condemns abortion and same-sex marriage and promotes abstinence and traditional gender roles. Their website is inundated with pamphlets, articles and advice columns. If you search “gender,” hundreds of responses pop up, including an article titled “How Gender Distinctions Affect Parenting.” The article explains how men and women have opposite dispositions and, therefore, contribute to parenting differently depending on their gender. A man’s job is to “deliver the goods” and he “tends to be active, aggressive, competitive and dominant.” A woman, in contrast, “seeks security and prizes modesty” and “desires equity and submission in relationships.” While Focus on the Family’s stance on gender appears extremely traditional and conservative, it’s not that far-flung. The Bible establishes separate gender spheres and patriarchal values within its first few pages.

In one version of the Christian telling, the creation of man and woman was sequential. First came God. From God came Adam. And from Adam’s ribcage emerged Eve. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, the renowned suffragist, explains how “woman was made after man, of man, and for man, an inferior being, subject to man.” The very order of creation places men before women.

When Eve plucks the glistening apple from a tree in the Garden of Eden, God punishes her. Eve’s curiosity and desire for knowledge—which some scholars believe to be an inspiring act of female willpower—is labeled and taught as the first “sin.” In the Book of Genesis, God says to Eve, “I will greatly multiply thy sorrow and thy conception; in sorrow thou shalt bring forth children: and thy desire shall be to thy husband, and he shall rule over thee.” In essence, giving birth will be painful, and women must be subservient to their husbands. While the Bible can be interpreted in a myriad of ways, there is little wiggle room in the line: “He shall rule over thee.” Many Christians will not take this literally, but some will—like Focus on the Family and Ahriana’s childhood Catholic church. But these messages also exist outside of those institutions: we see it in the predominance of male CEOs, in the slurs and catcalls men make to women as they walk down the street, in the astounding reality that the United States has had 43 presidents and none of them have been women. Religious values seep under the skin of our secular nation.

Even Kate Holbrook, the Chaplain of Colorado College, acknowledges her own struggle of being a female spiritual leader. She explains how over 2000 years of religious practice created a desire for men to hold leadership positions. Because of this, many people (including women) find comfort in a male God and male religious figures. As a woman defying the ingrained system, Kate sometimes finds it hard to hold authority.

And there are so few women within the Bible who offer an alternative image of what womanhood means. Take a look at the Virgin Mary, another female Christian protagonist. She gives birth to Jesus, the son of God, by—like her name suggests—abstaining from sex. She’s famous because she’s a virgin who produces a powerful, important man. Carol P. Christ, a feminist theologian, describes Mary as a “perpetual virgin that transcends the carnal sexuality attributed to most women [in the Bible].” Eve and Mary offer two options for women: either be condemned for your curiosity or be valued for your virginity. Can a woman find validation for her sexuality or her power within the Bible when so few positive role models exist?

***

So what if God was a woman—how different would our world be if a strong, powerful woman, glowed on the panels of stained glass windows inside of churches? What if, when a woman prayed, she prayed to a God who looked like her? What if men devoted their lives to believing in and respecting a woman who created the world?

“So what if God was a woman—how different would our world be if a strong, powerful woman glowed on the panels of stained glass windows inside of churches? What if, when a woman prayed, she prayed to a God who looked like her?”

From a hypothetical standpoint, the world would most likely be different. But in reality, it’s a lot more complicated. It’s unlikely that the authors of the Bible would describe God as female due to notions of gender at the time the Bible was written. Kate wonders, if Jesus had been a woman, “would [she] have been listened to?” While we can’t easily answer that question, we can look to other cultures that worship goddesses. The Ancient Greeks, for example, believed in both male and female deities. We see a similar structure within Hinduism and many indigenous faiths. However, these religions are polytheistic and difficult to compare to a religion such as Christianity that believes in a singular God. And in both Greek mythology and Hinduism, there is still a supreme male god: Zeus and Vishnu, respectively. Rosemary Radford Ruether, another feminist theologian, writes within her book “Sexism and God-Talk,” that we must “question the assumption that the highest symbol of divine sovereignty still remains exclusively male” (61). If God—or Vishnu, or Zeus—still holds the highest throne, women will always be beneath him. Like Ruether, many women have dedicated their careers to “questioning” this hierarchy within religion. But like most things, an answer isn’t easily found.

***

After being denied the position of altar girl, Ahriana Platten questioned her faith. Her mother left her no choice: she had to remain Catholic until she left the house. Years later, though, Ahriana stumbled across a faith that granted her ownership of her femininity and allowed her to reclaim some of the power stripped from her as a young girl: Goddess spirituality, a pagan movement led mainly by western women that incorporates goddesses of different cultures to provide a “feminine face” of the divine. Ahriana studied it for twenty years.

Goddess spirituality embodies the belief that women are powerful, creative and independent beings—notions that resist typical depictions of women within Christianity. In her article titled, “Why Women Need the Goddess,” Carol P. Christ explains, “The Goddess is a divine female…a symbol of the life, death and rebirth energy in nature and culture, in personal and communal life...the Goddess is symbol of the affirmation of the legitimacy and beauty of female power.” Ahriana explains how goddess spirituality provides many “faces” or “archetypes” of femininity. She wrote an article about one of them, a goddess named “Yemaya,” or “Sea Goddess,” of the Yoruba religion. Ahriana describes Yemaya as: “the ocean, the essence of motherhood, a protector of children and, as goddesses go, [she] is powerful.” For Ahriana, Yemaya’s presence is healing.

But even though faith in these goddesses, such as Ahriana’s, provides women with a divine being that may resemble themselves more closely than a male God, they don’t completely disestablish gender norms. Ahriana believes there are certain inherent masculine and feminine traits. For example, men are more “linear” and “oriented towards intellect” while women have “nurturing mothering, [and] birthing” inclinations as seen in Yemaya. Ahriana used her studies of goddesses to help her redefine and “heal” her relationship with a male Christian God, and now identifies with a God that represents both a feminine and masculine face. Her messages were somewhat conflicting. Although it seems goddess spirituality grants women empowerment and perhaps reshapes the identity of a Christian God, it still limits men and women to specific gender roles. In “Sexism and God-Talk,” Ruether argues that defining God as both male and female (written as: “god/ess”) still labels God as the powerful father and Goddess as the nurturing mother—which further promotes stereotypes of each gender.

Other feminists and theologians take a different route. Elizabeth Cady Stanton decided, against the disapproval of many, to rewrite the entire Bible—in 1898. She titled it “The Women’s Bible” and deconstructed each passage to identify sexist language and explain the misrepresentation of women. She even mentions the use of male pronouns and questions whether a “dual pronoun” of “they” would make more sense. While Stanton’s work is both enlightening and progressive, the clergy denounced “The Women’s Bible” right after she wrote it, preventing it from having any immediate impact on religious teachings at the time. While some ministries may preach with gender-neutral language, the Bible of today does not look like Stanton’s: it still uses the male pronoun and limits women to narrow gender roles.

Although women like Ahriana Platten, Rosemary Ruether, Carol P. Christ and other feminist theologians found alternatives to the male-dominated Christian faith, their views are not widely publicized. While Goddess spirituality may offer empowerment to women deprived of equality within their religions, it’s not completely accessible to the general population—because how many people know about it or have the chance to study it for twenty years? For the most part, people grow up believing there’s just one God—and he’s a man. There is, across the country and world, a desert of female role models within religion. There’s this empty, sandy, dust-ridden place stretching across the globe and breathing within the hollow of many women’s bodies—a silent place, a questioning place. A place where women are looking for someone to believe in, someone who represents who they are and who they strive to be.

Just last month, a series of “love letters” were addressed to First Lady Michelle Obama by various acclaimed authors. One of them, written by Nigerian novelist and feminist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie in response to Obama’s speech condemning Donald Trump said, “All over America, black women were still, their eyes watching a form of God, because she represented their image writ large in the world.” Obama is a woman who reclaims the word “female” and allows woman to grasp it, hold onto it and believe in it, too. This inclination for the idolatry of public figures and stars goes beyond Obama—countless other women fill the role, whether it’s Beyoncé or Emma Watson or Malala Yousifazi. These women are, in many aspects, “a form of God.” They do not fill the desert, but they are oases.

When Holbrook was asked what the world would be like if God was a woman, she said: “[women would] have the notion that you hold the world, that you’re valued.”

There are so many ways for women to be valued—so many ways we can change. Maybe you imagine God as a woman who wears a pantsuit and likes apple cinnamon muffins. Maybe churches use gender-neutral language when addressing God. Maybe we rewrite our documents to use inclusive words. Maybe you study goddesses, or listen to Michelle Obama or any other woman who empowers you, or maybe you begin with yourself. Allow yourself to hold the world. Plant a seed within your desert and allow it to grow.