Where were you when—?

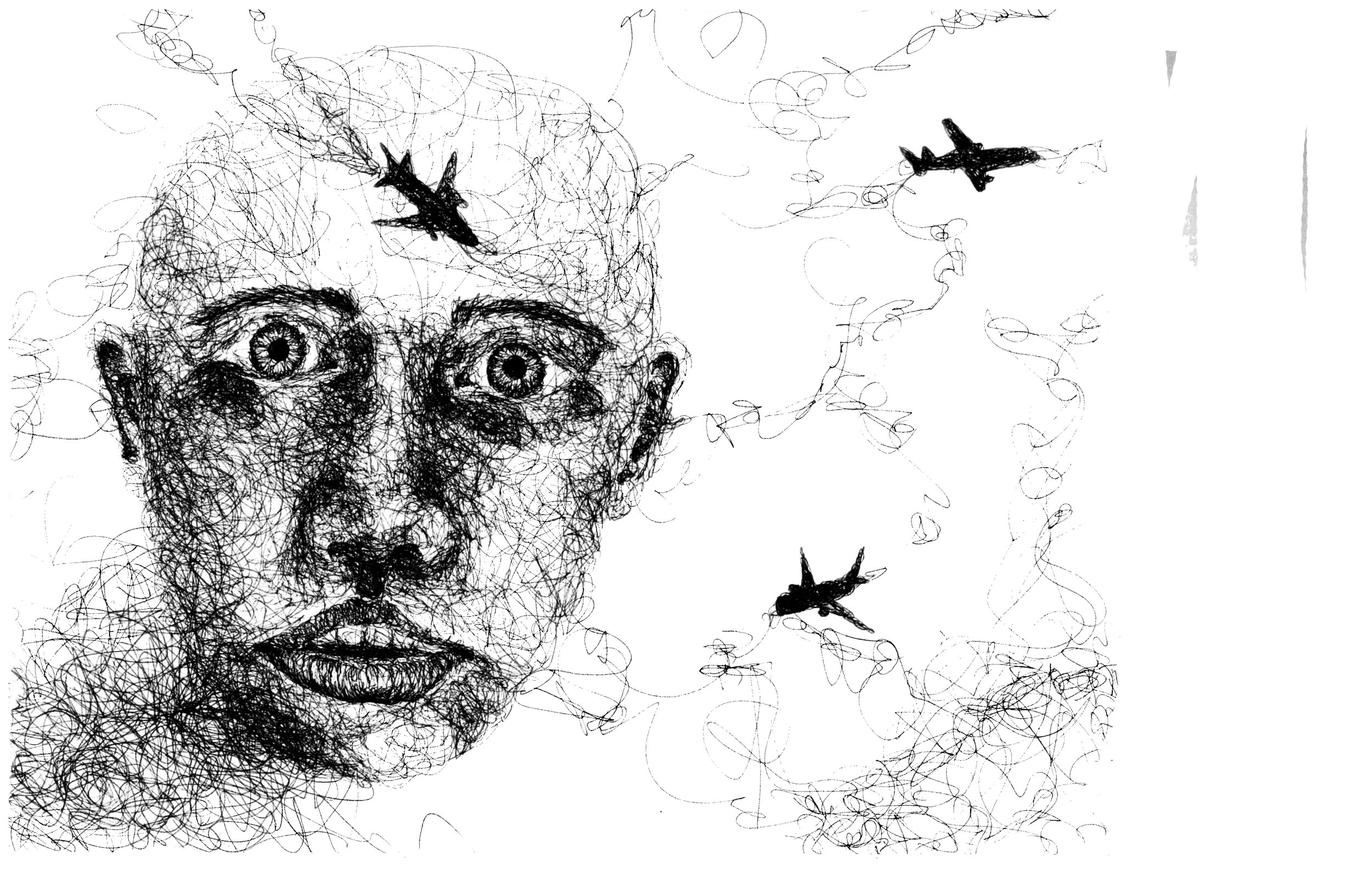

by Thomas Crandall; illustrated by Emma Kerr

"The thing about that day is that it was the most perfect day. There wasn’t a cloud in the sky. It was a beautiful 75; it was gorgeous,” recalls junior Tess Gruenberg. “[There was] this eerie silence… the city is never silent, it’s always bustling, that’s what makes it New York. I remember walking up 5th Avenue because there was no transportation—you couldn’t get taxis obviously and I was holding my dad’s hand…I remember him saying, ‘Don’t look behind you, I know it’s gonna make you want to look but don’t…of course the 6-year-old, 7-year-old that I am looks straight behind me. It was the most terrifying moment because it was this beautiful blue sky that was just being engulfed by this burrowing blackness of smoke…and that moment was the last thing I remembered.”

The term flashbulb memory, coined by psychologists Roger Brown and James Kulik, “is a memory that’s encoded during an emotionally dramatic event, something that’s highly significant…even if it’s [understood] after the fact,” says Lori Driscoll, a professor in the psychology department. “The context is encoded in much more detail than with regular memories.” During an emotional or traumatic event, the brain releases high amounts of dopamine, acetylcholine, norepinephrine and serotonin simultaneously. Acting in synchrony, these neurotransmitters act as amplifiers in the brain’s cerebral cortex, helping to encode the most contextual detail during that event as possible. The brain then creates a cohesive storyline of the experience, shipping the memory to another part of the brain for consolidation, similar to consolidating a picture into a JPEG file.

In their 1977 study on subjects’ memory of traumatic events such as the Kennedy assassination, Brown and Kulik found most subjects remembered where they were, who they were with and when they found out in detail. Unlike an actual flash photograph, not everything was fully preserved. Most perceive normal events like what we eat for breakfast as routine, and thus not as important to encode thoroughly.

Despite the brain’s vast ability to form and store memories, the process of retrieving memories, or recall, becomes complicated. Each time you recall a memory, the hippocampus needs to reconsolidate that memory, and with each recall the memory’s narrative becomes more malleable and plastic. These flashbulb memories are usually the memories we are asked to share the most, and recalling that story more often can potentially alter the memory. The National Memory Study of 9/11, which conducted surveys one week, one year and three years after the attack, found that between the first and second surveys, only 63 percent of details (with the over 3,000 subjects across seven US cities) remained consistent.

One of the most iconic events of our generation was September 11th. Violent and visceral, 9/11 seared itself into the minds of all citizens, especially Americans who had family or friends affected. Yet current Colorado College students were very young at the time, and just beginning to form autobiographical memories.

“I was in third or fourth grade, and [our teachers] made a conscious decision…to not tell the elementary school students,” recalls senior Sam Huestis, who grew up in Pennsylvania. “So the whole day went on normal…then they bussed us home. I hopped off the bus and my young neighbor, Ellie Pikle…like four at the time, she’s like, ‘Oh, a plane crashed into a building and it fell,’ and I’m like, ‘What is she talking about?’ And then I walked inside and my parents were at the television and they were just like, ‘You gotta come over here.’ I didn’t even realize…what it meant.” Huestis remembers going to the high school’s football game on Friday, and being mad that his birthday party got cancelled the next day. He admits most of the details are hazy except “this one memory of [Ellie], this little girl running up to me and babbling incoherently about a plane crashing.”

During a particularly emotional experience, the brain tends to focus directly on the thing triggering that emotion, allowing us to remember that trigger in detail, but at the expense of other contextual information. “My mom came and picked me up…and I just remember her saying that where Dad worked had been hit,” remembers senior Siena Faughnan, originally from New Jersey. “First thing, I was like, ‘Are we going to be homeless, are we going to live in a box?’ and I was very excited about that because it seemed like a fun adventure.” Faughnan remembers being brought to the principal’s office after lunch, and her mom crying, but after that the memory fades. “I remember walking home… but I don’t really remember anything else…[or] what we said on the walk home,” she confesses. Others, like senior David Mulcahy, from outside of Boston, remember vivid snapshot images, such as the color of his teacher’s hair. “[I was] sitting on the ground because my perspective was an up angle…my teacher’s name was Abigail, principal’s name was Marsha,” recounts Mulcahy, “I just have this visual of white hair versus her blonde hair…it’s one of the things that I can pair with the memory, but after that it kind of…not stops, but my direct memories versus family stories…overlap.”

Despite sensing a lack of accuracy, most students still felt confident in their memory’s validity. Senior neuroscience major Will Cohn, from the Chicago suburbs, although consciously skeptical of his memory of that day, distinctly recalls seeing a postcard with firefighters on it at his friend’s house.

“I don’t remember specifically what we were doing in class, but for some reason I needed postcards…so I went over to my friend’s house before school,” recounts Cohn, “I remember there was this one postcard, and who knows if this is accurate at all, but it was literally a postcard of firemen putting out a burning building.” He admits, “I’m a neuro major so I’ve questioned this memory, like, ‘Is this real?…Who knows, but what I remember, that is what’s true to me.”

Confidence in details of a normal event memory usually indicates accuracy, yet because flashbulb memories are highly emotional, confidence and accuracy tend to separate. “Even though we’re soaking up a lot of the context, we’re not actually encoding things faithfully,” Driscoll said, “so when we’re asked to recall a flashbulb memory, we may have a lot of information…but it’s not really great information necessarily.” Surveys suggest that where people were when they heard about 9/11 remained the most accurate detail, with 89 percent accuracy after a year and 83 percent accuracy after three years. The least accurate detail was emotional reaction; after a year, subjects’ accounts retained only 40 percent accuracy. Most students said they felt confused when they found out but distinctly remember their moment of recognition.

“I have two older sisters and they were sitting on the ground, and I was on a bouncy medicine ball, and my mom explained what happened. And I remember I stopped bouncing. I can’t remember what she said, but I stopped bouncing and I slid off the ball at one point,” recalls junior Caroline Dodson. “I was so shocked by it…and I know when I fell off it wasn’t because I was upset, it was because I was surprised.”

Others, when asked to interview, didn’t think they remembered the day clearly until, as they retold the story, moments surfaced.

As freshman Julia Greene began talking about her class that day, she suddenly remembered a specific moment. “Actually, I think there’s one moment I do remember, which was crossing the room to go to the bathroom and seeing the TV on in the teachers’ lounge, and the teachers all kind of looking so concerned and desolate,” Greene said. “I just remember adults looking concerned, and that as a 5-year-old is something you can’t pick up on the details of…but you know that something big is going down.”

Depending on the circumstances under which we recall a memory, we may include or omit certain details depending on our audience. “Recall is interesting because it requires us to pull that thing out of memory, but then also to process that memory in the areas of the brain where we used to encode the memory in the first place,” Driscoll said, “so as you’re hearing people talk about the event, you’re recalling your original memory of the event, which was separate, but it’s now being experienced at the same time.” Because you use the same cortices to experience and to store a memory, you remember its details as if the memory were happening for the first time, and outside stimuli in the moment may become incorporated into the original file. Driscoll describes, “When you’re recalling something…you have to consolidate it into the hippocampus again, [and] all the other things that come up that are new sometimes get tied in as if they were part of the original reality.” After recall, the memory returns through the hippocampus back into storage, so that “It runs through that same machinery…in its altered state,” like a backup system that overwrites old files.

Caroline Dodson’s older sister Rachel, 10 at the time, remembers the day quite differently. “My dad was on a business trip, so I know it was just my mom who sat me in the living room to tell me… I think she told all three of us at once,” Rachel said, “but I don’t really remember the conversation where we were actually told.” Both Caroline and Rachel remember their dad was away, but here the sisters’ memories diverge. Caroline distinctly remembers their nanny Beatrice consoling her by placing a hand on her shoulder, while Rachel doesn’t remember Beatrice being in the room at all. After asking Rachel directly if Beatrice was in the room, Rachel says, “[it’s] vague… maybe Hannah and Caroline [were] on the couch with my mom in front of us, and my babysitter on the left.” Rachel also doesn’t remember Caroline falling off the ball. “I don’t remember any of that, and I actually doubt that she is remembering that correctly.”

In addition to memories being subject to alteration during recall, an emotional event like 9/11 can also be subject to certain biases. “When you recall the memory, you realize how important it is… and so it may be vulnerable to bias or to elaboration in such a way that people are wanting details from you, something that is emotionally poignant for example, [and] you might add that in when it really wasn’t all that poignant at the time,” says Driscoll. On 9/11, she recalls that she was in upstate New York about to teach a class on Ethics and Biotechnology. After sending her students home, she remembers her husband, an EMT, going to the city to work. Yet because so many of those affected either passed away or survived mostly unhurt, his role as an EMT was actually limited. When recalling her 9/11 story, Driscoll even admits she is subject to elaboration. “Sometimes I recall it like, ‘Oh my god, these students of mine had family members that were affected by this and some of them didn’t show up because they were freaking out,’” confesses Driscoll. “I just think about how close I was, could I see the smoke?…It’s so vulnerable to your over-elaboration.”

Huestis, recalling the memory to himself the night before coming in to interview, actually misremembered who told him the planes had crashed. “I had been remembering that it was not Ellie Pikle who told me but Ellie’s younger brother, Cole Pikle,” Huestis admits, “until I did the math and realized it was not Cole, [that] he was only one at the time.”

Whether or not our memories of 9/11 are accurate, we recall that day no less vividly. The dilemma with flashbulb memories lies precisely in that the details we remember are so genuine, there exists a social pressure to share these details as poignantly as possible.Yet, every time we re-experience something, we modify its narrative. “Every time you recall a memory…when you put it back in it’s altered in some way,” reiterates Driscoll. “It’s like a very precious and fragile book – you love it, you want to explore it, but every time you touch it you damage it.” Driscoll suggests recording your reaction to an event immediately after it happens to preserve a memory’s accuracy, but even video or journaling doesn’t minimize the unspoken pressure to overelaborate. Flashbulb memories aren’t disingenuous; ironically, it’s the overwhelming expectation of authenticity that threatens these most genuine, emotional experiences.