Why it might not be a coincidence

by Dana Cronin; illustration by John Jennings

With admissions decisions looming, I sat in my college counselor’s office seeking words of comfort. I had applied early decision to Colorado College, and there was not much else I could think about for those few days than how crushed I would be if I were denied.

“Don’t worry, you’re in,” Mrs. Meineke told me.

I wondered if she was only saying that because she knew my dad went to CC thirty years ago.

But she was right. I got in.

I was so ecstatic when I found out, and my dad was very proud. But a little part of me couldn’t help but wonder if I was only admitted because I was the daughter of a CC alum. Did I really earn my spot?

The tradition of legacy students traces back to the 1920s, when the country was facing an era of anti-immigration sentiment. In his book, “The Chosen: The Hidden History of Admission and Exclusion at Harvard, Yale, and Princeton,” UC Berkeley professor Jerome Karabel tells the story of elite colleges using legacy as a tool to weed out qualified immigrants—mostly Jews hailing from Eastern Europe—from admission. The college’s reasoning was that every foreign student to be admitted took a spot away from another Anglo-Saxon male, “the probable leaders and donors of the future.”

Legacy played a huge role even through the 1950s, particularly at Princeton. In 1958, the legacy admission rate at Princeton was 70 percent. An old pamphlet from the Princeton Alumni Council reads, “No matter how many other boys apply, the Princeton son is judged from an academic standpoint solely on this one question: Can he be expected to graduate? If so, he’s admitted. If not, he’s not admitted. It’s as simple as that.”

Although the legacy hype has been somewhat diminished, it’s still prevalent in the modern admissions system, mostly at Ivy Leagues. In fact, this year Harvard only accepted around 5.8 percent of regular admission students but accepted around 30 percent of legacies. Similarly, Yale accepted 6.7 percent regular admission and between 20 and 25 percent of legacies. At Princeton, it was 8.5 percent versus 33 percent. Keep in mind that all of these numbers are self-reported.

The practice occurs at non-Ivy universities as well. Take the University of Texas at Austin, for example. In 2013, the school’s president, Bill Powers, was accused of admitting unqualified students, allegedly overriding admission decisions for 73 students who had a combined SAT score of less than 1100 and a GPA less than 2.9. The UT system reviewed the situation and found that a lot of these students were sons and daughters of UT alums. However, they also found that the percentage of these under-qualified students was relatively low, and thus didn’t take action.

So why do universities bend the rules for legacies? According to a New York Times op-ed piece by Evan J. Mandery, their incentive lies mainly in fund-raising: a parent is more likely to donate to their alma mater if their kid gets to go there too.

However, this doesn’t happen everywhere. An admissions counselor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Chris Peterson, blogged about his disdain for the whole concept.

“I personally would not work for a college which had legacy admission because I am not interested in simply reproducing a multi-generational lineage of educated elite. And if anyone in our office ever advocated for a mediocre applicant on the basis of their ‘excellent pedigree’ they would be kicked out of the committee room,” he wrote.

Other universities may be cracking down on the practice as well. Take Kristi Murray’s case, for example. Murray is currently a senior here at CC. However, she has an extensive legacy at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; she could practically map out a family tree of UNC alums including her dad, aunts, uncles and great-great grandparents. She applied to UNC four years ago and got in largely, she thinks, thanks to connections she had within the university.

“I had access to so many people, I even got to talk to the dean of the journalism school,” she said.

However, three years later when her younger brother applied, he was rejected.

“I think we’re pretty similar students…I don’t think our applications would’ve been wildly different,” she said.

Both Murray and her brother were good students and were qualified to attend UNC. Though apparent at some top-notch universities, the legacy factor is, for the most part, somewhat arbitrary. In other words, it might help but it’s definitely no guarantee.

In my experience, every other CC student you talk to has a parent who went here. In fact, on my very first day at CC, I walked into my Mathias forced triple packed with the families of my two roommates, and as it turned out, all three dads were CC alums.

But maybe I’m imagining it, because actually only 10% of CC students are legacies. And for the past 10 years, that percentage has stayed relatively the same (no pun intended).

However, the legacy factor definitely does play a role in CC’s admissions process. Remember filling out your CC application? There’s a question on there dedicated solely to listing your relatives who went to school here.

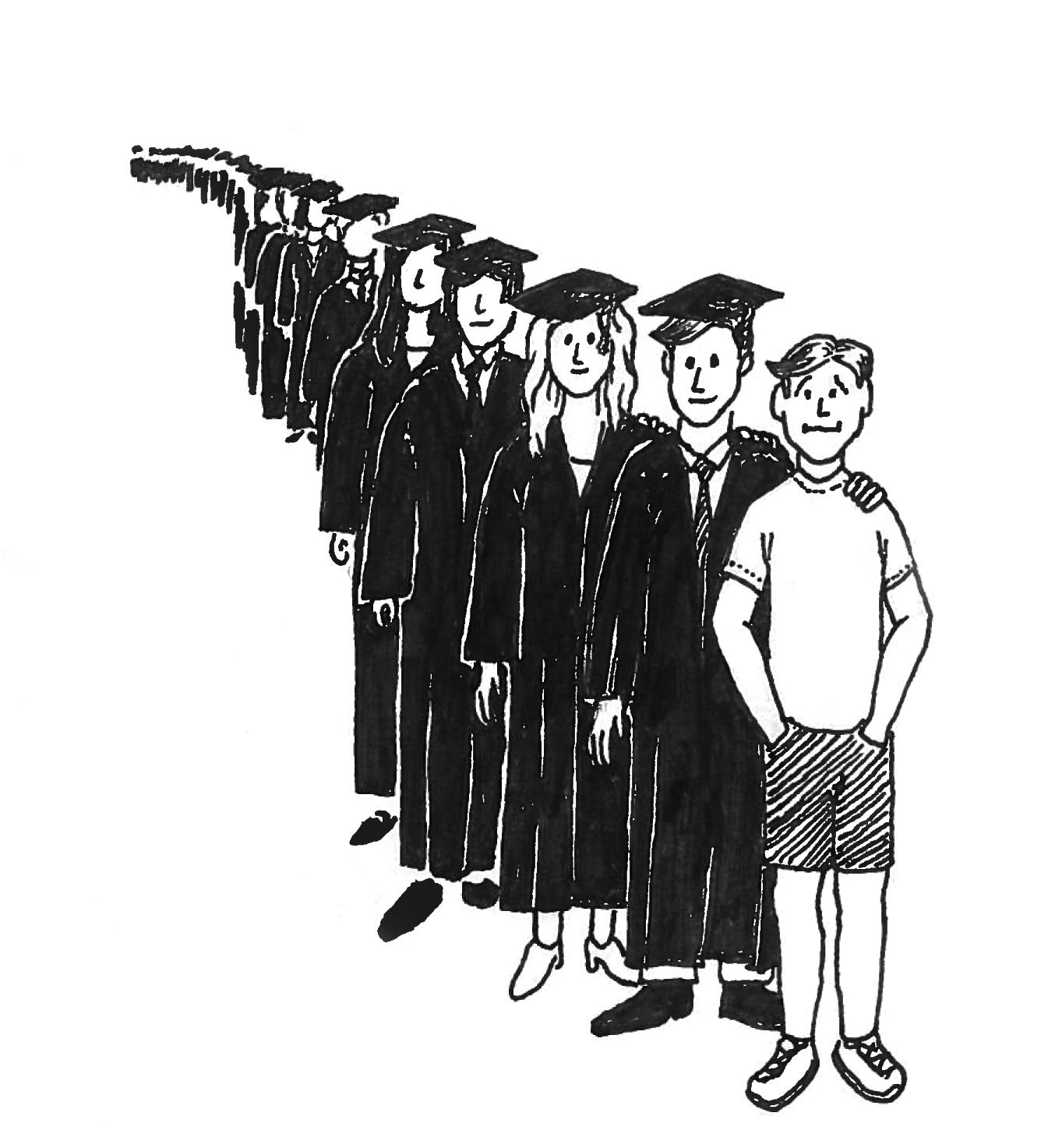

Here’s how it works: After the admissions staff weeds out students they know they want to accept, as well as students they know they can’t, they’re left with a big chunk of contenders in a middle category referred to as “the bubble.” These are the students that staff members feel would be successful at CC but that they can’t accept without some deliberation.

In order to filter through the bubble, admissions officers apply 55 admission targets, criteria based on ideals they set forth each year for creating a model CC class. These mostly include factors like race, geography and socio-economic level. And although legacy isn’t one of the 55 targets, it is part of the conversation.

“I would include that fact in the discussion,” said Carlos Jimenez, Director of Admission for Outreach and Recruitment. However, he says, “There’s so much other stuff we would weight more than that characteristic.”

It’s hard to get into CC, he says. It doesn’t matter who you are.

With an acceptance rate around 8-9 percent this year, he’s right—it is very hard to get in. In fact, as of a couple years ago, the parents of legacy applicants now receive a special letter in the mail while they’re waiting for the release of decisions. The letter recognizes their son or daughter’s legacy, but goes on to say that their admittance isn’t guaranteed.

However, it’s no secret that having legacy does give an applicant an extra leg up—however small—that regular students just don’t have.

So why does CC look at this at all? To put it gently, CC alumni aren’t the most generous with their checkbooks. While they have a lot of love for their alma mater, said Kerry Brooke Steere, the Director of Annual Giving, they aren’t the best at “articulating that love in terms of philanthropy.”

Monetary incentive aside, perhaps CC has other interests in taking an applicant’s family tree into account.

“It’s incredibly gratifying to know that alumni want the same experience for their sons and daughters, or grandsons and granddaughters,” wrote Vice President for Enrollment Mark Hatch in a post on the CC Bulletin. “We pay careful attention to these applicants, particularly because many legacies are better prepared for what CC will bring, given their familiarity with the college.”

Along those lines, Carlos Jimenez says legacy students are perhaps better prepared for the CC environment.

“We would expect a legacy applicant to have good insight and know why this place would be good for them,” he said.

He says they also value fostering connections with their alumni.

“The community here hopefully extends beyond your four years here as a student,” he said.

The controversy surrounding legacy is, understandably, a big one. It has even been negatively compared to affirmative action in that it unfairly promotes certain student groups above others. Its history as a tool of discrimination isn’t pretty, either. The fact that CC brings legacy into the discussion at all is, in this light, surprising. However, admissions officers are transparent in their motives and claim it plays a very minor role during admissions season. They just value their alumni, and, in a way, this is their way of giving back.