The sister cities of Colorado Springs

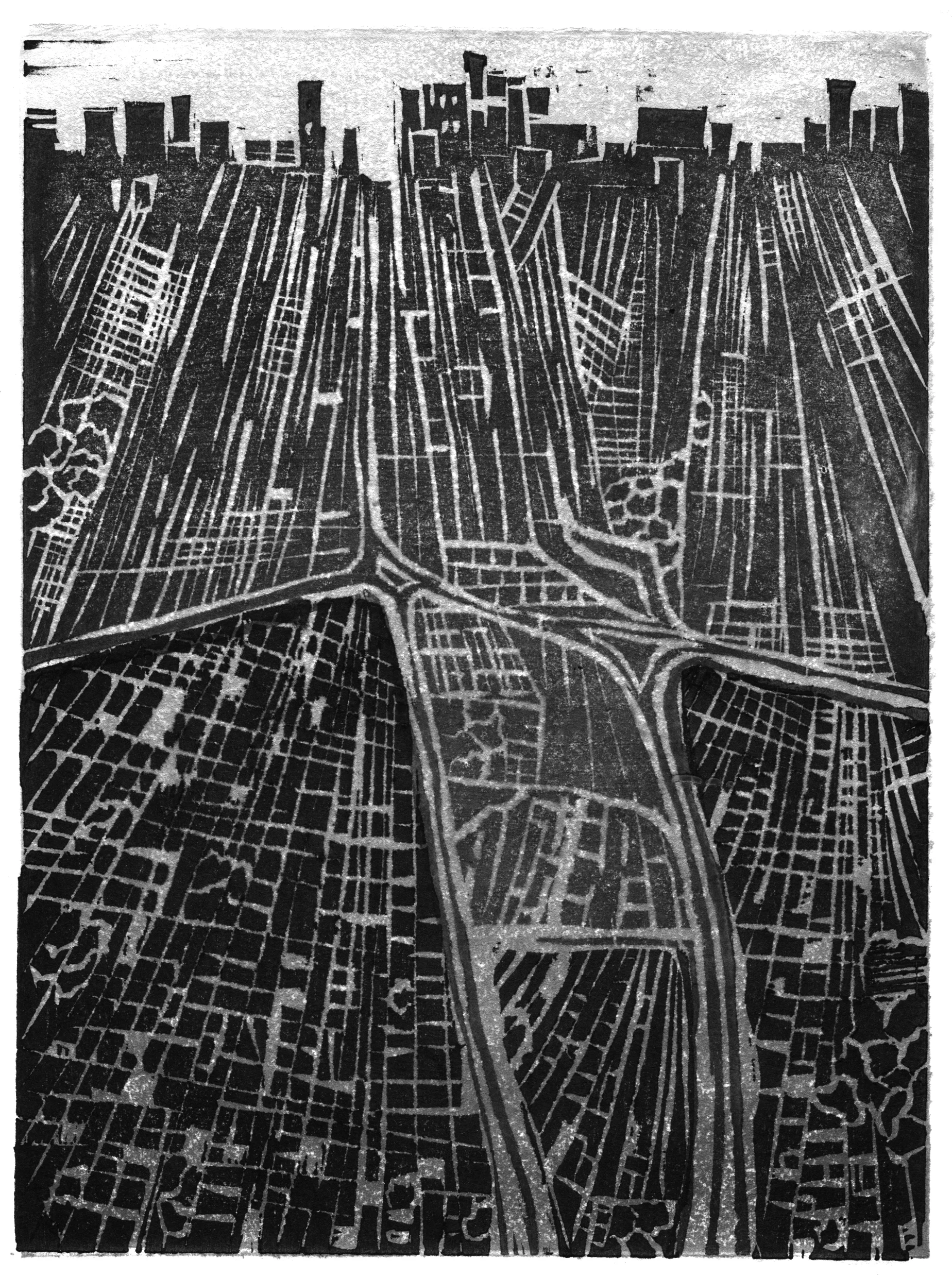

by Jack Queen; illustrated by Anna Kelly

I’m sitting on a patio with Dr. Dan Hannaway, Chair Emeritus of Colorado Springs Sister Cities International. According to the sprightly retiree, “It’s a big title that means I have no responsibilities.”

Hannaway has volunteered for 25 years with Sister Cities International, an organization that facilitates municipal agreements between foreign cities to strengthen cultural and economic ties. The goal is to promote “citizen diplomacy,” which holds that person-to-person interactions—anything from athletics to education to the arts—can promote peace by building trust and mutual understanding between nations.

“People-to-people interactions can probably accomplish more in the long run than formal diplomacy because—and this is my expression—people can really ‘let their hair down,’” Hannaway says with a playful grin. “You can express something as an individual without worrying about what the State Department thinks.”

While Colorado Springs is hardly an international hub, it boasts seven sister relationships: Ancient Olympia, Greece; Bankstown, Australia; Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan; Fujiyoshida, Japan; Kaohsiung, Taiwan; Nuevo Casas Grandes, Mexico and Smolensk, Russia.

It’s an eclectic mix, and with the exception of Ancient Olympia (Colorado Springs is home of the US Olympic Committee), I initially failed to see what beyond some signed papers makes these cities our “sisters.” It almost seems like someone threw darts at a world map to cobble together this little family.

Hannaway is quick to dispel my ignorance. Bankstown, it turns out, served as headquarters for the U.S. Olympic team during the 2000 games in Sydney.

“And Fujiyoshida sits at the base of Mount Fuji,” Hannaway says, gesturing to our slightly less impressive Pikes Peak, visible through the trees of his backyard. This similarity was enough to inspire a tourist from Colorado to initiate the Springs’ first sister city arrangement in 1962.

Other relations are a bit more tenuous. “Kyrgyzstan has some similarities with the mountains—it’s a very picturesque country,” says Hannaway.

The growth of Sister Cities has also loosely traced the contours of geopolitics since the program’s inception. Initially, it focused on mending fences with post-World War II Germany and Japan. (Those two countries still have the most U.S. sister cities). As the Cold War intensified so did the profusion of sister cities, and eight years after Nixon’s opening to China in 1972, San Francisco paired with Shanghai to form one of the first links between the US and a previously hermetic People’s Republic.

This new sibling relationship between the U.S. and China alarmed Taiwan.

“The people of Taiwan thought, ‘We are being left out because the U.S. has recognized mainland China,’” says Hannaway. “So they did an all-out shotgun attack on the U.S. trying to establish sister cities with a lot of cities in the United States, including Colorado Springs.”

When the Iron Curtain fell, a group of Colorado Springs residents, including Hannaway, sought to gain a sister city in Russia. They settled on Smolensk, one of Russia’s oldest cities, which stood square in the path of both Hitler’s and Napoleon’s invasions.

A newly independent Kyrgyzstan was soon to follow after one of its diplomats visited the Sister Cities national office in search of a suitable match. They settled on Colorado Springs in 1994.

It’s a damp Wednesday evening, and a throng of students mill about Armstrong Hall awaiting the screening of Reel Rock 10, an annually-produced climbing movie. I edge past them and head upstairs for a very different viewing experience and a taste of “citizen diplomacy” in action: a screening of the Russian film “The Cuckoo,” jointly organized by the Colorado College Russian Department and Colorado Springs Sister Cities. (The sacrifices we make for you, dear reader.) Each of the seven Sister Cities programs in Colorado Springs is headed by a director with a broad mandate to pursue the organization’s mission—the promotion of friendship, world peace, cultural understanding and mutual economic reward—as they see fit. This includes anything from the annual visits of Fujiyoshida high school students to a recent Kyrgyzstani delegation that came to Colorado Springs to learn about water conservation methods.

I stroll into Max Kade Theater on the third floor and am greeted by Natalia Khan, a professor of Russian with a delightful accent and animating grin. As we exchange pleasantries, I fear I’ll be the only one to show up, but soon Dr. Hannaway arrives with a small retinue of foreign friends. More people trickle in as I sit awkwardly amid the light hum of Russian that fills the room.

The film is set in occupied Finland during World War II and centers on a trilingual love triangle in which none of the participants understand a lick of the other’s native tongue. It makes for a comedy of errors that nearly ends in tragedy.

The film’s celebration of our common humanity—even in the midst of industrialized carnage—seems fitting for a Sister Cities event. In the movie, it’s person-to-person interaction that keeps the Soviet solider from killing the Finnish Nazi conscript and gets the Finn laid by the native Lapp girl they shelter with. It also forges strong bonds between the three and, in the end, the apprehension, even contempt of their first meeting has given way to an unspoken respect and kinship. The divisions between them—wartime allegiances, culture and language in particular—are not enough to keep them apart.

After the credits roll, I meet Stephanie Shakhirev, the chair of the Smolensk program and President of Colorado Springs Sister Cities. She’s a big believer in the power of ordinary citizens to maintain peace between nations.

“People-to-people diplomacy is recognized around the world as one of the best ways to reduce tensions,” she says. “It allows you to laser through all the BS you hear from politicians and world leaders.”

Which isn’t to say world leaders are totally divorced from these relationships. Last month, Chinese president Xi Jingping began his first official state visit to the U.S. in Tacoma, Washington,of all places. It turns out that particular suburb of Seattle is a sister city of Fuzhou, China, where Xi first cut his teeth in politics as a member of the Municipal People’s Congress. And a childhood visit to another sister city, Muscatine, Iowa, left such an impression on Xi that he returned there in 2012 to personally facilitate the largest Chinese purchase of U.S. soybeans in history.

Shakhirev, however, isn’t trying to peddle beans. Her goal is to make Sister Cities a “vanguard of international affairs for Colorado Springs.”

She believes, rightly in my opinion, that an international quality is what elevates cities to the top-tier; it is a mark of prestige when foreigners are attracted to a city, and their presence adds a cultural richness that distinguishes a place from the bland homogeneity you often find in Middle America. I ask her if she really thinks that these small-scale cultural exchanges are that effective.

“Yes, I do,” she replies emphatically. “The presence of internationals enlightens a community. It creates tension, in a good way, and challenges people’s perceptions.”

She agrees, however, that Sister Cities’ influence in the Springs has waned significantly from its zenith some 15 years ago. The organization has very little funding and receives no direct financial support from taxpayers. While it solicits corporate sponsorships and individual donations, the group’s total operating budget barely flirts with $10,000 annually. (To put that in perspective, the Carnivore Club’s budget last year was around $12,000.) In addition to covering CSSC’s dues to the Sister Cities International in D.C., the city provides a few in-kind services—offices and administrative staffing—but the organization’s mandate is severely constricted by lack of funding. It occupies a “unique but nebulous place within the city structure.” This problem was immediately apparent to Shakhirev when she came on as president a year ago.

“It took me five minutes to realize we didn’t have the numbers we needed,” she says. “There wasn’t anything going on.”

Sister Cities’ lack of financial support in the Springs stems from a weakness in the fourth component of its mission: economic benefit. Simply put, the lack of demonstrable increases in trade reduces the incentive to invest. While no concrete plans have been made to stimulate trade between sister cities, Shakhirev considers this her main priority, and strategic planning talks are underway with the El Pomar Foundation to reimagine this aspect of the program.

One part of the program that has enjoyed a lot of (figurative) buy-in from the city is the recent partnership with Ancient Olympia, Greece. Spearheaded by Harris Kalofonos, a native Greek who works in Team USA’s wrestling department, the agreement includes the Young Champion Ambassadors initiative, which is holding an essay competition among local high school students to select an ambassador to the 2016 Olympic torch-lighting ceremony in Ancient Olympia. The winner will be one of the first to carry the torch on its tour around the world to inaugurate the games.

The importance of informal relationships in shaping world events should not be understated, however rose-tinted the notion may be. A classic case of informal diplomacy comes from an era when the doomsday clock was four minutes to midnight and peace seemed uncertain as ever. Samantha Smith was 10 years old in 1982 when she wrote a letter to Yury Andropov, the newly-appointed head of the USSR’s formidable secret police. After congratulating Andropov on the new job, she sought reassurance that the Soviet Union would not attack the U.S. and reminded him that “God made the world for us to live together in peace and not to fight.”

The steely Andropov was touched by the letter and responded personally, inviting Smith to visit the USSR. This led to more exchanges of “goodwill ambassadors” and was perhaps one of the first tiny cracks in the Iron Curtain.

The episode was an example of “soft power,” or the use of cultural and economic influence rather than tanks and bullets to advance U.S. interests abroad. Its effectiveness is contested—Donald Rumsfeld, unsurprisingly, was not a fan—but fostering cultural exchange with cities around the world seems like a no-lose proposition. And it certainly wouldn’t hurt at a time of rising global tensions and a general erosion of U.S. legitimacy around the world. If more people are exposed to Russian culture, for instance, it stands to reason they would see the common humanity in our latter-day archrivals and temper their mistrust. In a time of mounting U.S.-Russia confrontation over Ukraine and Syria, it’s as important as ever for people to feel at least some solidarity with the Slavic “Other.”

Our global interconnectedness makes it unprecedentedly easy to connect with foreign culture. In this light, groups like Sister Cities may seem archaic. But without this institution, it’s doubtful that many residents of Colorado Springs would feel inclined to seek out Russian or Kyrgyzstani culture on their own. There is also a much deeper connection at play here, namely the physical act of visiting and hosting foreigners.

The presumed benefits are, of course, impossible to quantify. How can we really know if the U.S.’s vast network of sister cities—now over 2,000 strong and covering 145 countries—has contributed in any meaningful way to the past six decades of relative peace? I suspect it pales in comparison to the spillover effects of globalization, namely the ease and affordability of international travel and the diffusion of U.S. popular culture across the world; blue jeans may have chipped away at the Iron Curtain more than starry-eyed Samantha Smith’s visits across it. Xi Jingping’s boyhood travels to America were clearly important to him, but in the context of growing confrontation between the U.S. and China, could his nostalgia for Iowa cornfields really affect his strategy? And while citizen diplomats don’t have to worry about what the State Department thinks, they aren’t the ones who determine our foreign policy.

Even if Sister Cities provides no meaningful benefits, it can’t be said that it does anything bad—or that it imposes a direct burden on taxpayers. And giving a local high school student the chance to carry the Olympic torch is pretty damn cool. Will that result in world peace? I think it’s safe to say, unequivocally, no. But there isn’t any harm in taking a baby step toward it.