Motorcycle culture and one club’s efforts to do things differently

by Nathan Davis; illustrated by Charlie Theobald

On May 17, 2015 a shoot-out in Waco, Texas between rival biker gangs left nine dead, 18 injured and 165 arrested. Inside the bathroom of a Twin Peaks (a “Breastaurant” a la Hooters specializing in “eats, drinks and scenic views”) a scuffle turned to a brawl. The struggle moved from the bathroom onto the floor of the restaurant and, as it escalated, to the parking lot. Eventually, under the noontime sun, around 100 bikers were punching, kicking, clubbing, stabbing and shooting one another.

One witness told the Waco Tribune, “There were maybe 30 guns being fired in the parking lot, maybe 100 rounds.” When law enforcement arrived at the scene, they came under fire and returned shots.

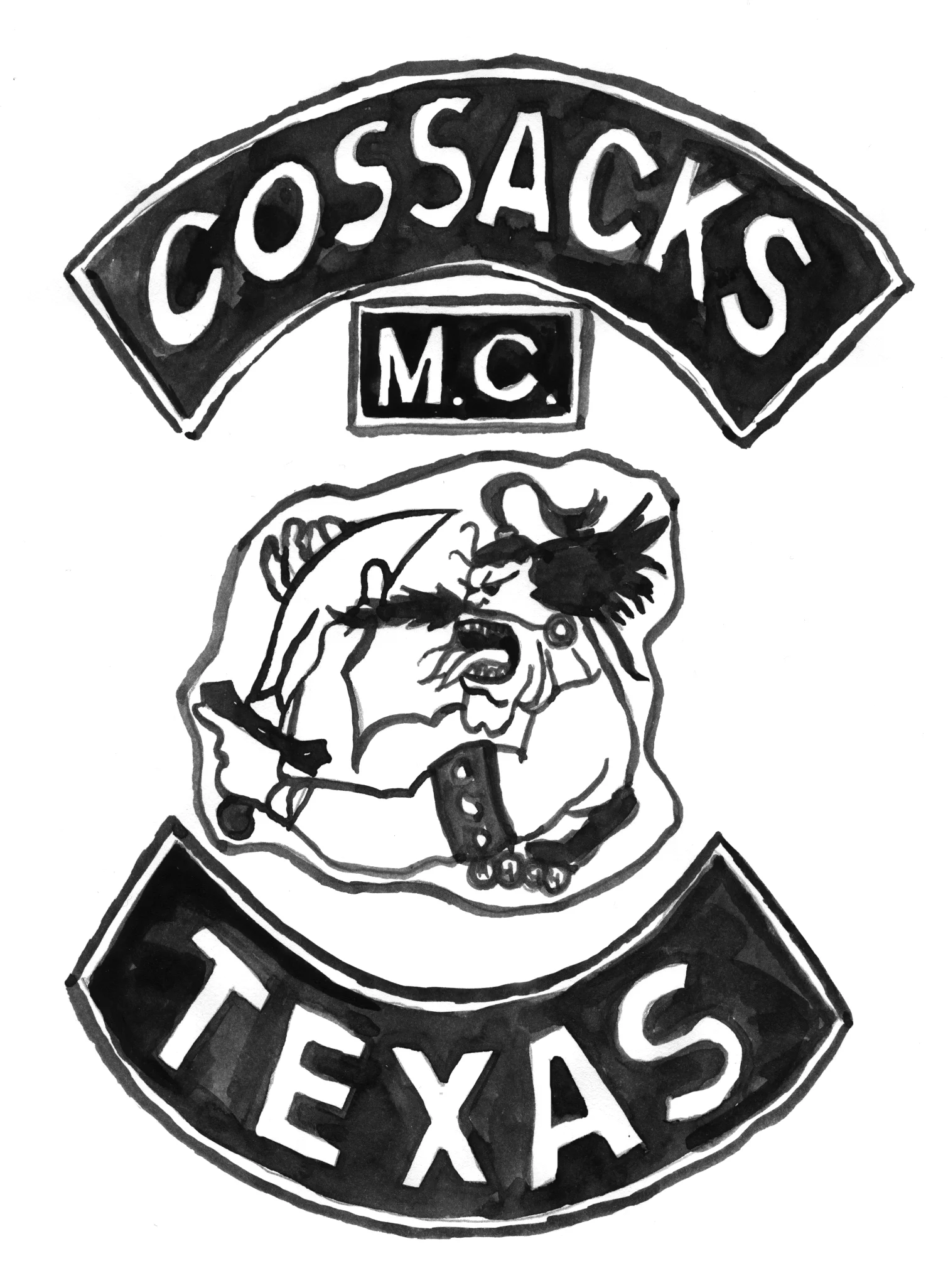

The shoot-out, between the Cossacks and the Bandidos, two gangs haggling over territory and respect, made news several days straight. Shots of a strip mall lot covered in blood, bodies and Harleys fit the front page like a glove.

Aside from the stray rumble of an engine or the rev of a motor, this is likely the last you’ve heard of biker culture.

* * *

“Sensationalism.” In his central Carolina accent, Cgar almost spits the word.

Cgar is the Vice President of the Iron Order Motorcycle Club. He’s been in Iron Order for nine years and has been riding bikes since he was a teen in Fayetteville, North Carolina. He speaks quickly and passionately, often leaving one idea for another mid-sentence. No matter the subject he tries to be upbeat, or at least pragmatic.

But when the conversation turns to the portrayal of bikers in the media, be it Waco or “Sons of Anarchy” (a TV show depicting a fictitious biker gang), he grows slightly more terse, inflecting his words with a touch of frustration, a little resentment even.

“When someone puts in the media ‘Oh yeah, Iron Order, they raised $10,000 for the local homeless shelter,’ y’know, ‘Oh yeah, that’s a great feel good story.’ That’s on page 9 of section C of ‘Living.’ But the thing in Waco, the shooting in Waco, is on page one, front page, in color pictures.”

His frustration is understandable. Iron Order tries very hard to walk a fine line in the biker world, to navigate a sea of stereotypes that confound a lot of motorcycle clubs (MCs). They want to maintain the ethos of a biker club—Cgar waxes poetic on “the thrill of riding, the wind in your face,” and you can feel the cool aluminum when he talks about cracking a can of beer—but at the same time, they want to be the good guys. They work tirelessly to remove themselves from the criminal reputation tied to biker culture, to live the outlaw lifestyle of a biker within the confines of the law.

Iron Order members are prohibited from using drugs. All chapters are required to host at least one community service event per year, and many host more. Gazoo, the Vice President of Iron Order’s Colorado Springs chapter, even says that from time to time the police will wave at Iron Order members as they pass by. He even goes as far as to say, “We work closely with law enforcement.”

They still have a good time (Cgar: “Now you come to our parties and you’ll think ‘oh my god, these guys are nuts’…We got women who run on the bar naked. At midnight you’ll see three or four bras hangin from the fuckin’ ceiling fan”). And they still live like bikers (He adds: “I’m not a golfer, y’know. I don’t play golf. I smoke cigars and I drink Crown Royal and I got tatoos up and down my arms, y’know, and I ride Harleys and I drive a pick-up truck”). They just follow the law while doing it.

By the estimation of all the Iron Order members I talk to, most clubs in the MC world are law-abiding. Gang activity applies only to a select few clubs, and even among those, they say, crime is usually confined to a even fewer chapters.

Even so, no matter how many fundraisers they host or how many police wave as the guys whip past, Gazoo recognizes that stepping out in public wearing leathers turns heads and draws unfriendly glances. “They stereotype us — there’s no ands, ifs or buts about it.”

It makes sense. To a non-indoctrinated onlooker, the distinction between peaceful motorcycle clubs and violent biker gangs can be hard to catch. Aesthetically, it often comes down to as little as a patch on the back of a jacket. If you aren’t a part of the biker world, the leathers on Gazoo’s back look a hell of a lot like the leathers on the back of a Cossack, a Bandido or any other club.

Cgar puts it bluntly: “When you see a big burly biker dude, what’re you gonna think?”

“I don’t get offended by it. I understand…People are just ignorant, and I mean ignorant in the way — not of not being intelligent, but ignorant in that they just don’t know. You don’t know what you don’t know, and they just, they don’t know.”

For Cgar, the stereotypes are just facts, not discouragement. “The stereotype is removed when you say ‘Yes ma’am’ and ‘No ma’am’ at the restaurants. Or you open the door up for the little lady comin’ out. Y’know, you go to Cracker Barrel, or whatever restaurant, and you’re walkin’ in and the lady’s walking out, a little blue-haired lady, and you open the door for them, and she says, ‘Thank you’ and you say ‘You’re welcome, ma’am’…Granted, the perception or stereotype is out there, but if you act like an animal then of course you’re gonna keep that perception up. But if you don’t act like an animal and you act like a human being then slowly but surely you can whittle away that perception.”

Cgar’s optimism is as contagious as it is surprising. When he talks, it’s not hard not to get the impression that for every biker opening fire in a Twin Peaks parking lot, there are two more at a Cracker Barrel opening the door for a little blue-haired lady.

On Thursdays, the Colorado Springs chapter of Iron Order (the ‘High Altitude Crew’) get together at a bar on the north end of town for Guys’ Night. The bar, Good Company, is nothing if not conventional: wall-to-wall TVs playing the Ravens/Steelers game, an offshoot room for pool and darts, a four corner bar in the center. The waitresses are cute, but it’s no breastraunt. Twelve bikes sit outside in the strip mall lot, unnoticed.

The Iron Order guys occupy the back half of the bar and some of the patio. There’s no question they’re bikers: leathers, chains, beards, tattoos. Gazoo, easily in his 60s, rocks a goatee that drops at least six inches off his chin before flaring out to both sides. His head is covered by a jet black Iron Order do-rag.

They’re loud and they’re rowdy, but no more than being at a bar warrants. Other than appearances, they’re 12 guys at a bar eating pizzas and nachos, drinking beers and sodas, talking bikes and girls. For two or three hours the beer flows cold, the love runs deep and that’s about it.

Most of the night is spent heckling one another. “Her thighs were as big as my waist!” Gazoo jeers at Rawr, a younger guy with a scruffy blonde beard and a backwards white flat-brim, apparently known for taking home bigger girls. At least 15 minutes are devoted to stories of escapades involving Jameson and tasers (who drunkenly sat on their taser, who got duped into trying to tase a lightbulb, the time Gazoo ordered shots for anyone who tased Rawr on his ass). Kapooyah, the club President, lets everyone know about his four-year-old daughter putting on his old Batman costume and chasing their dogs around the house. Skid constantly takes heat for riding a “crotch rocket” (a sport bike). They fall into a rhythm: chat, taunt, collective belly-laugh, repeat.

A few minutes are dedicated to chapter business.

“Brothers!” bellows Gazoo, and the guys assemble around his table.

They vote to send $300 to the family of a brother from Nebraska who died in a wreck. An 85-year-old women rear-ended him on the highway. The mood turns somber for a few moments, but before too long the guys are deciding whether they want to have a bonfire tomorrow night or go to a different bar and do ‘‘Family Night.’’ Family night it is. Page 9, Section C, ‘‘Living.’’

The guys excitedly tell me about all the meals they prepare for school kids in underserved districts every Christmas or the “Cancer Camp” benefit they hold. More than anything, their chests swell and their eyes glow when they tell me about the brotherhood. “These guys really are my family,” says Rawr, who, aside from Iron Order only has a mother as far as family goes. Gazoo, who has a wife and 10 dogs, says the same. At least half the brothers at Guys Night this particular evening are current or former military. For a lot of the ex-military guys, a motorcycle club provides the bond that the military once did.

* * *

Biker culture follows a stringent hierarchy. Each state is controlled by a dominant “One Percenter Club.” One Percenter is the biker terminology for outlaw motorcycle clubs, clubs that aren’t registered with the American Motorcycle Association. The title “One Percenter” comes from a comment purportedly issued by the AMA that “99 percent of motorcycle clubs are law abiding. It’s just the one percent that are outlaws.”

Hells Angels is a One Percenter club, as are the Bandidos. Not all One Percenters are criminal organizations, though many are on some kind of FBI or ATF watch list. Publicly, most One Percenter clubs maintain that they are law abiding, with only select chapters surreptitiously involved in criminal activity.

A 1999 raid of Sons of Silence, the dominant One Percenter club in Colorado, turned up 24 machine guns, four pipe bombs, four hand grenades and 10 pounds of methamphetamine. This raid, the result of a lengthy undercover operation, targeted two clubhouses, one in Commerce City, the other in Colorado Springs. The Colorado Springs clubhouse was less than two and a half miles from the Colorado College campus.

To found a club, a biker first has to receive the blessing of the dominant One Percenter (the “Dom”) in that state. This is the club which controls all MC activity in a state, legal or criminal.

In some instances, non-One Percenter clubs in a state are required to pay dues to the Dom. Most states have a system of ‘support clubs’ devoted entirely to the assistance of the dominant One Percenter of that state. Dominant One Percenter is a position typically won by force, be it intimidation or violence directed at other clubs in the state.

The primary function of the One Percenter system is to enforce a strict code of respect. This can mean anything from resolving disputes between clubs to punishing those who step out of line. Stepping out of line might be engaging in activity in territory under the purview of a One Percenter without consulting them first or disrespecting a One Percenter member or club. They administer justice, but do so more swiftly and emphatically than police would be permitted to.

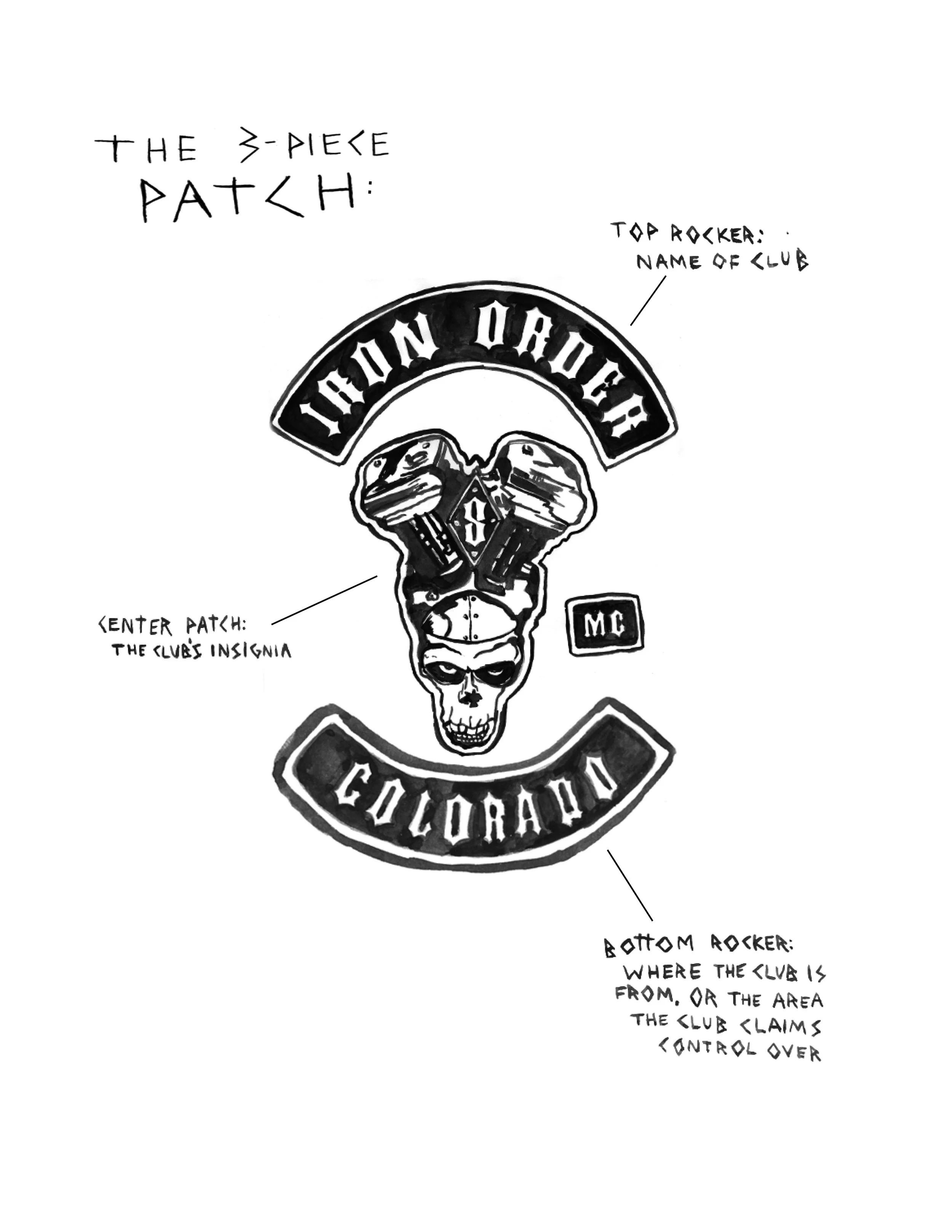

One Percenter clubs are identifiable by a diamond shaped “1%er” patch on the front of their leathers. All one-percenters, and a few other clubs granted permission by the Dom, wear a “three-piece patch” on the back. The three-piece patch consists of a downturned crescent patch declaring the club’s name at the top of the jacket, an upturned crescent at the bottom (the ‘state rocker’) declaring the area over which they are dominant and a patch in the middle with the clubs insignia. It’s a family crest.

More than a fashion statement, the three-piece patch is a sign of respect for tradition. It means that your club has agreed to abide by the protocols established by the dominant One Percenter of that state. Clubs take serious offense when another club wears a patch featuring a state rocker which they have not been permitted to wear. Wearing a patch without permission is a sign of disdain for the pre-established order, an order many clubs take very seriously.

One Cossack claimed that the Waco shoot-out, rather than a spontaneous eruption of violence, was premeditated by the Bandidos, who were angry over the Cossacks’ adoption of a Texas state rocker (the Bandidos are the Dom in Texas). Nine dead and 18 injured over some jackets.

* * *

Iron Order is an independent, non-affiliated club, meaning they found chapters without asking the blessing of the dominant One Percenter club. Though they don’t represent a competing interest to One Percenter clubs in terms of territory (or business, where applicable), this is a profound sign of disrespect for many bikers. To make matters worse, they wear a three-piece patch featuring a state rocker (to indicate where they are from, not where they control).

Even more than the perceived signs of disrespect, they ignore the conventions of the biker world. Law enforcement officers are permitted in the club. They won’t hesitate to call the police or communicate with them if need be. (“Silence is golden” is the rule for almost all other clubs.) They aren’t American-made bike exclusive. They permit anyone in their club, regardless of race. At one point, Cgar proudly proclaimed, “We got a couple guys who are Muslim in our club! We had one guy who’s cool as shit. He’s from Iran. He’d come roll up on his bike listenin’ to his Iranian music, singin’ and dancin’ and we’d be like ‘You silly-ass fucker.’ So we’d pick on him, but he’s a cool guy.”

This defiance of the biker code engenders a sense of pride in Iron Order members, especially the decision to adopt the three-piece patch.

“I’ve been Army since 1988. I’ve been to five different foreign countries, three different conflicts, y’know. I mean, I enjoy ridin’ motorcycles, but I also enjoy my freedom, and I don’t think anybody should be able to tell me what I can wear and what I can’t wear on my back,” says Cgar, his voice rising. “The U.S. Constitution gives me that freedom. The Bill of Rights gives me that freedom. The federal, state and local laws tell me what I can and cannot do, not another man.”

“It’s the man that makes the patch, not the patch that makes the man,” says Gazoo.

For the Iron Order guys, wearing a three-piece patch means emulating the nonconformity of the nascent motorcycle culture of the 40s and 50s. Except returning World War II vets were trying to free themselves from the complex of rules and customs of society, whereas Iron Order is choosing to free themselves from the complex of rules and customs of motorcycle culture itself. They exist within a paradox: outcast from an outcast society, defying those who stake their reputation on defiance.

It hasn’t always been pretty.

“Oh yeah, we’ve had issues. We’ve had members get in fights, get punched. We’ve had members get stabbed. We’ve had members get shot…Just for who we are. Because we’re Iron Order. Because we wear a state rocker,” says Cgar. He pauses to give it more thought. “I mean, there are so many ‘because-reasons’ why. Y’know?”

Gazoo, ever the no nonsense foil to Cgar’s romanticism, puts it plainly. “We’re not liked by the other motorcycle clubs. They get in our face every once in a while. They just flat don’t like us. Not at all. We’re pretty much hated… And we don’t care. We just don’t care.”

Cgar emphasizes that this is not the result of any aggression or proactivity on the part of Iron Order. “We’re not…we’re not the club of ‘Oh, if you do something to us, we’ll go back and do it to you.’ No. We’re a defensive posture club. If you confront us, we have the right to stand there and defend ourselves—and we will. And we have. We have. We’ve had fights. And we’ve fought back just as good as we’ve got it. Other people got hurt just as much as our guys got hurt. Some guys got hurt more than we did. I mean, I’m sorry. It sucks. I mean, we say ‘leave us alone,’ y’know. We don’t bother nobody.”

No matter. Poking around online, it only takes a few minutes to see the level of vitriol some other bikers will level at Iron Order. They get called out for claiming to be law abiding or for allowing law enforcement to join. “Posers,” “Fags,” “Pigs.” More than anything, the Facebook pages, message boards and blogs take the strongest offense at their use of a state rocker.

It’s equal parts incredible and bizarre to read as an outsider. Iron Order seems to be taking a stand against a system of deference and autocracy that pervades the world of motorcycle clubs. They represent an alternative to the rigidity of motorcycle culture, a refusal to abide by the contradictions of a culture which was founded in ignoring custom and is now as shrouded in custom as the Masons.

The strong sentiment that other clubs have against them feels inconsistent. Isn’t there a sense of pride in flouting the rules?

I’ve heard all the reasons they could give for why the community castigates them and still find myself asking “Why?” They stay out of the way of other clubs as much as possible. “The beer is just as cold at the bar down the street. It is. If we go in [to one of their bars], then we’re pokin’ a bear in the eye. We’re instigatin’ shit, y’know. Why? There’s no need for it,” explains Cgar. “Say you’re sellin’ bread and I’m sellin’ beer. I’m not gonna care what you do. Our club is not in competition with any other club.”

So what’s left? They lack respect, they ignore tradition: Isn’t that the point?

Iron Order is far from the only law-abiding club. Even if the bad-boy image is an important part of biking, the criminal activity it implies is only taken up by a sliver of the community. Waco might have been shocking, but it is largely unrepresentative and anomalous.

Still, the antagonism of Iron Order by the larger motorcycle world indicates a culture that is intolerant of anyone operating outside its hierarchical system which puts the most intimidating clubs, the clubs most capable of domination— and thus the most capable of turning criminal —on top. The tendency to vilify a club that’s minding its own business, a club that doesn’t pose a threat to the existing order is a product of such a culture. Gangs like the Bandidos and Hell’s Angels—the sliver—maintain their status for the same reason clubs like Iron Order are marginalized. 99 percent of motorcycle clubs may be law abiding, but, taken together, the tacit support they give the other one percent is empowering. So empowering, in fact, that there isn’t space for a club that says “let everyone else sell bread, we’ll sell beer.”

* * *

And on Thursdays, at Guys Night, it’s clear that’s all they’re doing.

Before I head out, the conversation turns to the annual Halloween party, which, after the Fouth of July, is the biggest party that the High Altitude crew holds each year. The guys chat excitedly about parties of years past: who got the drunkest, who had the best costume. Kapooyah expresses a little disappointment that he can’t be the Joker this year because it would mean shaving his beard, a compromise he is unwilling to make. Still, he lets everyone know that in general, the prices at Zeezo’s, a costume store on Tejon St., are only a little higher if you buy a costume instead of renting it. A few brothers behind us are having each other smell the e-juice for their vape pens and guess the flavor. “Vanilla ice cream?” one guesses.

If Iron Order wasn’t independent, neutral and non-affiliated, if they asked the blessing of Colorado’s dominant One Percenter, they would be under the yoke of Sons of Silence, whose Colorado Springs clubhouse, at the time of the ‘99 raid, featured a shrine to Adolf Hitler. Would they drink at Twin Peaks instead of Good Company? Trade their pens for pipes? Talk guns rather than costumes?

What is certain is that they’d have to retire their three-piece patch. The downturned Iron Order crescent would remain at the top, the logo of a skull with a motor coming out of its head would remain in the middle, but the upturned crescent featuring “Colorado,” that would have to go. It would take a few minutes at most. It would save them a lot of trouble on the road, in the bars and on the web. Regardless, they have no intention of doing so.