Faith and love in the virtual age

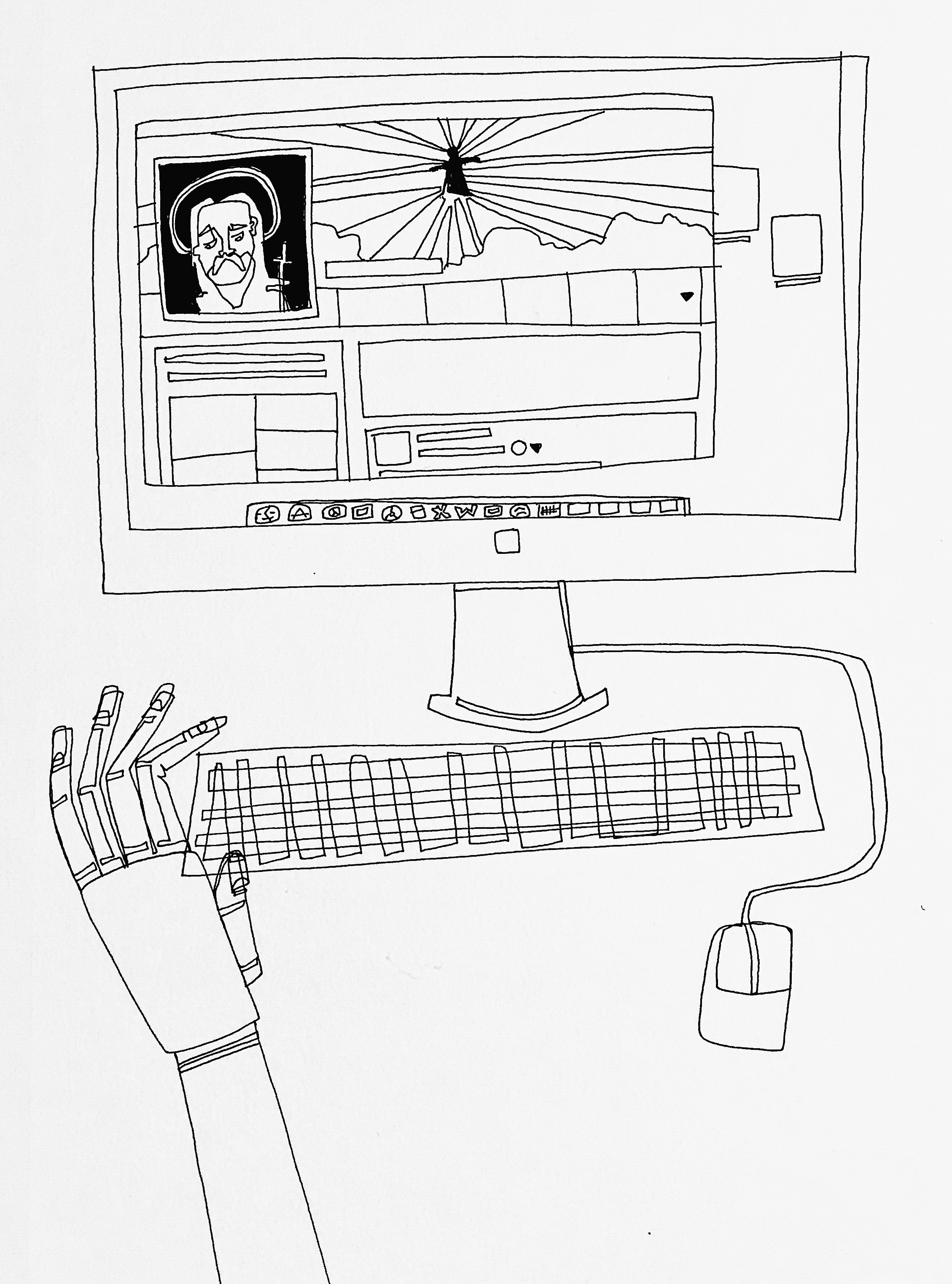

by Tess Gruenberg; illustrations by Morgan Bak

Seemingly out of thin air, a man appeared next to me, “You know you’re sitting in the seat of Hell, right?” Fashioned in all-black everything, his style refined, beat yet intentional. Beneath his feet, a well-loved skateboard. He laughed somewhat maniacally and pointed at my feet, “Look under you. A grate. No heat. Hell—how’s it feel?”

“If this is what hell feels like, count me in,” I replied arrogantly. He reached out his hand, “I’m Billy. Also known as Barry Lohan, also known as Billy Rohan. Call me Billy though.”

Billy exploded onto the table next to mine with a pack of cards, crazy glue, Marlboro’s, rolling cigarettes, paperclips and a tiny bottle of Hennessy. As soon as I could blink, he was dealing me into a game of blackjack with a dollar on the table, yelling out to people passing by. Saying: “Cool is the new currency, you heard?” and “You can’t buy swagger like that!” He was brilliantly post-modern. A professional skateboarder turned librarian. The man was a caricature of himself.

For about an hour we sat together under the red glow of the heat lamps and exchanged stories of moments well-spent. We spoke of the beautiful evils of astrology, the unrelenting power of a compliment and what Billy believed to be the four cornerstones of life: women, water, air and wisdom.

At the end of the hour, he fashioned me a ring out of the dollar bill that I won in our blackjack game, and when he gave it to me, he looked me directly in the eyes and said with all the conviction in the world, “We are our own kings and queens, our own masters.” His piercing light blue eyes wide and alive, “You, Tess, are your own God.” To which I replied, “No, Billy, I am not my own God. I do have faith something bigger than myself exists.” Billy shook his head back and forth, his grin cracked wide. I continued, “Though I’m not sure what that something is.” Billy chuckled, looked up from his skateboard and said, “That sounds like a copout to me.” And with that, he rode off into the night.

†

† †

I am not religious, but I do have faith. My faith is not a cop-out, but is attuned to the movement of my generation. For many Millennials, God is a murky word. According to Pew research, Millennials are the least religious of any generation, but also consider themselves just as spiritual as past generations. “Spirituality” has become the umbrella term for Millennials who have faith in something without engaging in religious practice. Like all generations, we feel the necessity to believe in something bigger than ourselves. We just want to practice faith in our own way.

We’ve all heard the generational mantra: “Yeah, I’m spiritual but not religious.” For Millennials, ‘spirituality’ is a term used to escape the rigidity of religion while maintaining the seemingly blissful state of faith. We understand the word ‘religious’ as dogmatic and oppressive, in opposition to spirituality. “I was shocked when I got onto campus,” said Emma Brachtenbach, a senior sociology major. “Watching the hostility towards people with faith. Just writing people off because they hold principles.” We tend to be contemptuous of any form of categorization, even though spirituality has come to be a narrow categorization itself. “People that identify with spirituality are de-categorizing their religiousness. But really, it just constitutes a different category for Millennials,” said Greg Smith, senior comparative literature major.

It is a categorization of a different kind—an ultimate refusal to be bound by any belief system at all. Spirituality is seen as free of systematic thought, and only has one only rule: to construct your own ideas of faith, to create your own God.

Millennials are known as the “Me” generation in part because we have the arrogance to create our own rules. But this so-called narcissism is not invented—it’s learned. The Millennial generation is the ultimate consequence of the goal of modernity, which is, in the words of sociologist Zygmunt Bauman, “to bring the world under our own management.”

“Now, we are at the helm, not nature, not God,” Bauman says.

Bringing the world under our own supervision meant creating our own truths. Whereas before, God was responsible for revealing truth to humanity, in modernity, humanity became responsible for finding the truth. Throughout the 20th century, the possibility of the truth (a singular truth) was challenged so thoroughly that the responsibility shifted to particular individuals to create their own realities.

This was essentially a move toward individualism, and it was a move that required the death of God. For it is now you - the subject - the master, who is at the center of the world. It is up to you to create your own truth. This progression ultimately led to us, the Millennials.

The advent of the Internet and personalized technology only compounded this sentiment of individualism. Digital technology has become the mediating force with which we live out our own truths. We all hold personal devices loaded with information tailored to users’ particular needs: to self-reflect, to be followed, to be rewarded for every action. We are individuals, self-affirming among a sea of other individuals, all connected.

The world is now a network—a network dictated by social media platforms that are a particular type of refuge, echo chambers that affirm our beliefs and validate our fears. We spend so much of our time in this network that it no longer seems relevant to delineate between the “real” world and the Internet. What we call the virtual is no longer a fake or illusionary reality, but is now considered a ‘productive’ mode of being, one that gives free rein to creative processes. “Originally, creativity was reserved exclusively for God, and the right to it was extended only to people who were endowed with a kind of divine ingenuity,” said Wolfgang Ullrich. Now, these virtual spaces allow us to create and fantasize our own gods. So it’s not necessarily true that we are our own gods, but that we have the power to dictate who and what our gods look like.

†

† †

I was once asked a question I never thought I’d answer truthfully:

“What is the most important thing you’ve learned in college?”

Upon attempting to pick one of my favorite philosophical theories, I froze. My face reddened with fear. A white wall emerged from some corner in my mind. Checkered with drawers full of blank pages, it consumed me. A deep breath spurred a spontaneous response that I had never even considered, “I learned that I must always be in love with something, whether that be a person, a concept, or an object.” I paused for a moment as the enquirer raised his eyebrows. I grinned, “But mostly a person.”

The evidence are these intimate, at times heart-wrenching, experiences of love. Love that, more often than not, turns into an unrelenting carving of humans into God-like figures. As Yiannis Ritsos, a modern Greek poet, once said, “my place is in the rocking—the superb swoon,” and I cannot help but attest that this superb swoon, this rocking, is awfully beautiful. Beautiful in the ways in which the swoon makes me come alive. Awful in that the compulsion for idolization can be toxic. I have little choice in the matter. I deify human beings because I don’t believe in a traditional notion of God. I fall in love because I need faith.

It is a dangerous game, though—intoxicatingly dangerous. It is to carve an idol out of a fear and call it God. To love a person into an idea. The person transforms into a virtual character in the narrative of my life. They become ripe for fantasy, their being a collection of impossibly vibrant vignettes. To deify a human is to kill the truth of their own reality. To deny them their mortality. To deprive them of a reality outside the abstraction I’ve created. An amalgamation formed out of my insecurities and securities alike.

The relationship becomes addicting, a seductive ride of constant analysis. One can never be bored: every pointed finger a hint, cracked grins pulses of ecstasy, every conservation a game of cherry-picking their words and sucking them dry. The idea that you can never un-hear something is wrong. You can. But eventually, the actual people become too different from the gods we’ve created. The illusion collapses under its own weight and the pain strikes just as intensely as the elation.

Still, I do have faith in the “superb swoon,” in believing other human beings can exist in ways that I cannot. And I don’t think the illusion always collapses. There’s a way in which you have to create an abstraction of someone to be to love with them, or even to know them.

But something strange has occurred in the past decade. The virtual spaces of social media take this act of abstraction to an exponentially higher degree. Personal technology has made it incredibly easy for us to worship ourselves and others. We have been given virtual mirrors onto which we can project perfect images of ourselves: profiles manufactured and maintained with constant care. Like Narcissus, we have mirrors that reflect precisely what we want to see. Virtual spaces allow us to invent in ourselves that which we worship in others.

We deify humans all of the time online. Kanye as Yeezus, Beyoncé as Queen B. We create our gods in these virtual spaces and then stalk them. And when we’re not spending hours scrolling through bits of insignificant information on the notoriously famous, we’re making each other into celebrities.

“Facebook is insane,” Greg said, his hands firmly on his head, as he shook it back and forth. “You start to deify other people’s profiles instead of that person. You look at their profile so much so that when you see them in real life, you see their profile and their content, not them.”

We all know how fun that is. The compulsive click-next, the right arrow, your best friend, searching for some distant tagged photo. But what you are really searching for is the embodiment of your idea of them. It’s a hell of a lot easier to fall in love with your idea of someone than it is to fall in love with the actual person. And what you’re really doing is falling in love with your fantasy. It is a self-affirming act.

Facebook functions by way of algorithms that are tailored to the user. The content is not random; it is organized, and it is for you. And the more you use the network, the better it gets at curating the content you love and the content you love to hate. And who you love and who you love to hate.

If you make someone into a god on Facebook, it knows. It knows, so it lets you see precisely what you love about that profile everywhere you look. In the virtual, then, the abstractions we create of others are unlikely to collapse because they are always being reified by social media. Whereas in person we are eventually forced to reconcile our abstractions with the physical reality of the individual, the internet keeps feeding us constructed versions of each other—versions that are custom-made to seduce.

Maybe this is why it’s so hard to disconnect. These social media platforms act as a substitute for the emotional retreat of religious communities. This is the reality of a world turned network, the result of the Facebook sanctuary. We need our screens to be the structure others long found in religion. They allow us to turn each other into the gods we are otherwise lacking. They give us virtual churches to replace the physical one.

Maybe Billy Rohan is right, if not in the way he intended. When we use social media, we are putting our faith into algorithms designed to reflect our own desires and fantasies. So, maybe we are our own gods. For in those moments, all we are doing is worshipping ourselves.

Part of the Toxic issue