In search of Joe Bolton

by Charlotte Allyn

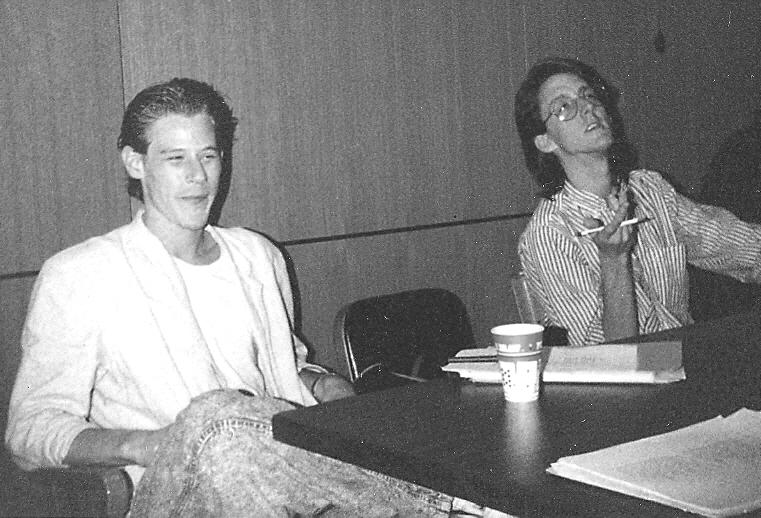

Bolton pictured on left. Photo courtesy of Rhoda Janzen.

There are American flags on every street in Cadiz, Kentucky, a small town in Trigg County. The town is small, with basic stores: a grocery, an antique store, a flower shop, a hardware store, a couple of bars. It is well maintained. I went there in the summer of 2013 to learn more about the poet Joe Bolton, who was born there. I didn’t stay long. There’s not much to see, and I spent more time driving around the surrounding farmlands, dotted with old cemeteries roamed by cows and horses then I did in the town. I was in Kentucky with funding from a Venture Grant to get a sense of the place Joe often wrote about, view a small collection of his work and correspondences at his alma mater, Western Kentucky University, and interview people who knew him.

I was introduced to Joe’s poetry in my Beginning Poetry Writing class when my professor, David Mason, mentioned him. A friend and I checked out his collected poems, “The Last Nostalgia,” from the library that day and I immediately fell in love with his writing: the precise but fluid language, the musicality and rhythm, the stories. In “The Lights at Newport Beach,” Joe writes, “If we were more than the sum of our desire/(But we’re not); if there were a language I/ could find to get beyond the opacity/Of zero. . .But I’m tired of words and all we turn/Away from. I just want to watch it burn.”

I was in love with his words and fascinated by his mysterious life. I thought that maybe if I knew more about who he was, I could tap into how he wrote. His poems were the music of a life I was living and not living—the foreignness of a young Southern man writing about the same beautiful world in which I was trapped, a world so beautiful that it is painful, a world where even the things we have we are already losing.

I did not know exactly where in Cadiz Joe grew up, or how long he lived there. I interviewed the musician and writer Tommy Womack, Joe’s classmate at WKU. He told me, “There would have been nothing intellectually satisfying for Joe in Cadiz. He would have been way too smart and way too sensitive for Cadiz, Kentucky.” Womack grew up in Madisonville, which is about a 35-minute drive north of Cadiz. He felt similarly about his own small town upbringing: “I hated my hometown for years and years. I hated the very buildings. Until you realize, I’m hating a structure. I’m hating an edifice.”

My classmates and I hardly knew anything about Bolton at all. Very little information about him is available in books and on the internet. Many of my classmates also loved “The Last Nostalgia,” and we often we read it both alone and aloud to one another. It was part of the basis for the tight-knit community Dave’s class became. Joe’s poetry is also stylistically admirable. His poems deftly move between form and free verse and are rich with lyrical spirit. We admired his skillfulness and learned from his work. Because his poetry impacted us immensely, he became a larger-than-life figure for us. His poetry is all at once gentle and wild, sorrowful and kind, and together, just like we were in our lives and just like life was with us.

I started my journey to find out more about Joe because the community in that class became such a significant part of my life. I wanted to learn more about this poet who, at an age not much older than my classmates and I were at the time, so accurately captured in his writing what it feels like to be alive and writing poetry. In “Song to Be Spoken, Not Sung,” he writes:

Say snow drifting through some small town at dusk,

And listen to the syllables die in your bare room

Like snow drifting through some small town at dusk.

Say Fall, rain! as the rain falls down on you

But know it would have fallen anyway.

Say this world and let it be enough, for once.

My classmates and I knew he was a student of Donald Justice, who helped edit “The Last Nostalgia.” We knew Joe started his graduate work for a master’s in Creative Writing at the University of Houston, then transferred to the University of Florida and nearly finished his master’s at the University of Arizona before he died. He published prolifically for his age, but died so young that he did not have time to mature creatively. As a result, he is not very well known. Michael Cox, now a professor at the University of Pittsburgh Johnstown, was a classmate of Joe’s at the University of Florida. He told me that once a visiting professor asked “who the professor Joe Bolton was.” The students laughed when they told him Joe was a student. The visitor was shocked that a graduate student had managed to get so many poems published in so many journals.

Joe submitted his thesis days before his death. We knew he killed himself, but we didn’t know how. A couple of students in the class wrote poems imagining different scenarios in which Joe died. In one version, he hanged himself from a tree.

I went to Kentucky with my parents. We made a road trip out of it—Kentucky to Nashville, Nashville back home to New York. In Kentucky we stayed in a bed-and-breakfast with blue floral wallpaper and a yard full of horses. The air smelled sweet and the humidity wasn’t as bad as I expected. We went to Keeneland in the early morning and watched the horses exercise on the track. In Nashville we went to the Country Music Hall of Fame and later met with the writer and musician Jeff Zentner. He didn’t know Joe but we met anyway; I learned about his passion for Joe’s work through social media. We ate barbecue at a picnic table. His wife and son came along too. She told me it was funny timing when I reached out to them because just days earlier someone had sent them a photo of Joe, the first one they’d ever seen. I knew exactly what picture they were talking about and since that time have only ever seen one other. Jeff told me, “[For] people who love Joe Bolton, it’s not a casual thing…it’s immediately. You feel evangelistic when you read his stuff…you have to share it.” When we got to WKU we walked around campus, quiet because it was summertime. At WKU’s library I asked to see the Joe Bolton Collection. The librarian brought it out—a gray box about the size of two shoeboxes, full of printed-out emails and handwritten letters. “This is it,” she said.

Joe started his undergraduate degree on a baseball scholarship, I later learned, at the University of Mississippi, I later learned, on a baseball scholarship, then transferred to WKU. When I met with Womack in a Mexican restaurant in a Lexington strip mall, he said Joe “looked kind of rock ‘n roll. That was how I defined people’s looks: prep, rock ’n roll and then the red necks, who were their own category. But Joe looked rock ’n roll. I had only experienced brilliance in the form of rock ’n roll artists. Joe was one of the first artists outside of rock ’n roll or comedy that I experienced brilliance in.”

Tommy’s description of Joe reminded me of how I felt about him—a rock star because he wrote poems with content that was familiar, relatable and sometimes identical to my own experiences and feelings. I felt like his poems accurately represented the joys and complications of both romantic and non-romantic relationships. He perfectly captured my constant nostalgia for a childhood that wasn’t yet over. He begins the poem “Adult Situations”: “These moves we make/To do and un-/Do each other/Must be lovely/From a distance.”

Many people I talked to described Joe as always wearing a leather jacket. Womack said it was black; the author Rhoda Janzen, who was Joe’s classmate at University of Florida, said it was tan. I also heard he wore Hawaiian shirts. Most recall that he gelled his hair and all agreed he wore glasses. He smoked. He had a deep voice. Michael Cox told me, “He kept a lot to himself,” but was also “very quietly likable.” The two played basketball together, although Joe “wanted badly to get me on a baseball field instead, where he excelled.” He was a romantic as well. I learned Joe married while in college and divorced before he graduated. He remarried soon after but then divorced for a second time. Womack said, “None of us were married, but he was. I never even thought of him as having an age.”

Everyone talked about that voice; how deep it was, how absorbing. Janzen said, “There was something about the gravelly voice, the crazy charm, the sheer brio, that disposed us toward him.” Womack called his voice “rumbling and deep.” An ex-girlfriend from WKU, Dr. Rebecca Flannagan said over the phone, “He had this incredibly deep voice and whenever he spoke it was as if it was the last word. And he knew that. He was always very aware of his presence and what his presence did to people.” She continued, “He told me that’s how he seduced women, by reading his poems aloud.”

Most people I talked to agreed that he was brilliant. Womack told me, “I was 19, I didn’t know much about humanity or the world or anything deep at all. I can’t say I got all of his poetry, but I can say when he spoke it there was brilliance. The whole class knew it. It wasn’t just that he was the number one guy in the class. There was no number two. There wasn’t any comparison.” Joe’s professor at WKU, Dr. Frank Steele, described him as “brilliant and original, spontaneous, full of life, just a really vital kind of guy. He was also tremendously idealistic and stubborn.” Steele relaxed the first time he met Joe in his office. Joe came in with a copy of “The Waste Land” and wanted to talk about T.S. Eliot. They talked about everything from that moment on, Steele said, whether it was movies or politics or literature. The poet Edward Hirsch, who taught Joe at the University of Houston, said, “I thought he was very special. And we’ve had some really talented poets, but I thought he was really, really something.”

Joe left a lot of places, and he looked back at the places he left. One of Joe’s ex-wives, in a letter to Justice, wrote, “I seem to remember a party at your house when you walked us to the door, made sure that I was driving, and told Joe that he was the oldest man you knew. That struck me then as very true.”

Yet Joe was only 28 when he died in Arizona in 1990. From letters and emails in the WKU collection I learned that people were shocked and but unsurprised by Joe’s death. A friend of Joe’s told Justice that, when she asked Joe what he dreamed of, he replied, “I dream, as always, of my death.” Around that time, I emailed a woman whose name I had repeatedly seen in emails to Justice and who, I realized, was dating Joe at the time of his death. I asked her if she would talk to me about Joe. She told me Joe woke her up one night and told her to watch. Then he put a gun to his head and shot. She did not reply to any of my emails again.

Joe was an alcoholic and, according to Steele, Joe’s father had been an alcoholic as well. Still, Joe kept up frequent correspondence with many of the people I interviewed—former professors, classmates and friends. He was a prolific letter writer, but many of his relationships were complicated. Janzen noted there was a “tragic beauty in Joe’s fierce reinterpretation of reality as romance.” Steele said that Joe seemed to be a guy who valued his poetry more than his life. This was a theme that many people reiterated. Flannagan said, “Everything was in for his writing.” Flannagan believes that for Joe, “Nothing was as good as the past, ever. Even when he was in the middle of something.” She continued, “He was negotiating behind my back when I was living with him. But he wrote sweet poems about me when we were broken up. He was trying to get back to something he had or had ruined. I almost believe that he screwed things up just to write about that.”

After hearing Flannagan and others talk about Joe, I started reading his poems a little differently. I started thinking about why he wrote them and what had inspired them. In doing so, I lost the clarity and distance that is necessary for a reader. When, in the second stanza of “Black Water,” Joe writes, “It is a Tuesday, and early June/And 1985/And it would be your wedding day/Were it three years ago/And it would be your anniversary/Had she not left you…/But it is simply a Tuesday, in June/In 1985/And you have woken up alone/To the life you live alone…” I no longer read it just as a reader. I started wondering who the “you” was and if this “you” really had left. I started having trouble separating the narrator from Joe himself.

Flannagan recounted other stories of living with Joe, like the time he tore apart entire bookshelves and dressers when he drank too much, or how he punched walls. Sometimes he painted then ripped the canvases apart. I heard a couple versions of a story where he tried to burn the beginning pages of a novel he had started. But he was apparently also enigmatic and fun to be around. He liked to play pool and guitar and talk late into the night. He had “this sort of James Dean method of lighting. He could scrape a match on his fingernail.” Flannagan said his parents paid his rent directly to the landlord so he would not buy booze with the money. He tried not to drink until 2 p.m., which was when class ended. She drove him most places because he was usually drunk. She said, “When his attention was on you, it was on you. And when it wasn’t, it wasn’t. You could never depend on him to do what he was supposed to do, be where he was supposed to be… but every other time he was great. He was always in situations where things were breaking. There was always breakage involved.” Before we hung up, Flannagan added, “I’m not sure he really loved anybody.”

But still, she’s glad she knew him. “It was bad by relationship standards, but it wasn’t bad; it didn’t ruin me, it inspired me to work at poetry, to see it more as a craft.” She was not angry with him, but I was. I felt like this person who had captured life so astoundingly, so delicately, had lied to me through his poems about the experiences of this world. Was it really the same world we were both in, if Joe spent most of his time looking back to the past? If he had never really loved anybody? If he had left his favorite professor with guilt and a girlfriend with a violent memory? When I asked Rhoda Janzen about Joe’s literary influences, she replied, “If you want to talk about Joe’s primary influences, I’d guess that the spirit of the intellectual age had less an effect on him than the spirit of alcohol.” What did it mean for me, as a reader, to read a poet whose life was not separate from his poetry, who maybe, I wondered, ruined things to write about ruin? Could I think of his work the same as I had before I knew about his life?

I understood that Joe suffered deeply from alcoholism and what was likely manic depression. I knew that a poet’s voice is not the poet. But I still felt a deep distrust of the truth of his poems after learning more about Joe. I stopped reading his poetry completely. I did not compile my interviews into a book, as I had planned.

A couple months ago, almost two years after I started the project, a friend of mine returned a Joe Bolton collection that I had lent him before I began the interviews and exploration. He had forgotten about it and found it in a stack of his own books. I reread “Black Water.” I reread “The Party.” I read “The Lights at Newport Beach” aloud and realized I no longer knew it by heart. But I liked reading the poems again; they did not make me feel sad or uncomfortable. I appreciated them for the first time in many, many months.

Joe’s poems reflect his genius. Sometimes I wish I had never started my journey to learn about Joe, but sometimes I am glad that I did. I’ve begun work to finish the project. I now think what I learned about Joe did not alter the truth in his poems, but the truth of the world as I knew it two years ago. A truth where you had to lose things a certain way or love things a certain way to write about them the way he did. Where he was not a larger-than-life figure but, instead, a very real person.

I learned that Joe didn’t actually grow up in Cadiz. Apparently his parents were from Cadiz but he was really from Benton. In the end, I decided, what difference does it make? I saw Cadiz. I believed it was the small town Joe spoke of. And, in a way, it was. In “American Tragedy,” Joe writes, “Kentucky, midsummer, sun going down—/Day like an empty shotgun shell, still warm,/Fragrant with dog shit and honeysuckle…” I experienced Kentucky how Joe described it, even though I was in Cadiz, not Benton. Knowing that there is still deep truth in Joe’s poems is like this; I read them differently now than I did before I knew about Joe, but that does not detract from their beauty. I’m just a different reader now.

What really made me uncomfortable about how Joe lived had more to do with who I am as a writer than who I am as a reader. I was startled to recognize my fear that the root of Joe’s brilliance was his inexorable suffering. If Joe’s life was his poetry then does this mean some sort of sacrifice is necessary in the life of a poet? Even though I knew it wasn’t true, I wondered if his depression and struggles allowed him to write the way he did. I knew what writing poetry felt like. But I was only in college and living the life of a college student. I didn’t know what it was to be a writer and live a writer’s life. Each year of college I became more and more serious about my writing. I began to realize that Joe was a talented poet, and his talent had nothing to do with his depression and his alcoholism. He was a very talented poet with a very real disease. I now think it’s more likely that being a poet was the one thing that kept him alive for his short 28 years.

Last week I talked to the poet Art Smith, who knew Joe when he was at Houston. I asked Art about the question of sacrifice. He simply said, “Poetry helps me live my life better.” I realized, after talking to him, that writers don’t suffer for the sake of their writing. They don’t need to make sacrifices for the sake of their writing. They write to make sense of the abundant suffering already in the world, and to make it less painful. In an email about Joe, he wrote, “It’s odd but I think about him frequently. I think partly because of what he did not accomplish. He did not have the time to mature that wonderful voice and rhythm that was always so evident in his work.”

Joe left some poems behind, but he also took with him the words he did not yet write. I, too, think about what he would have later accomplished. But I still believe poetry makes lives better and suffering bearable. I know this because in my Beginning Poetry Writing class, his poetry did that for me.