Fat shaming and the art of vulnerability

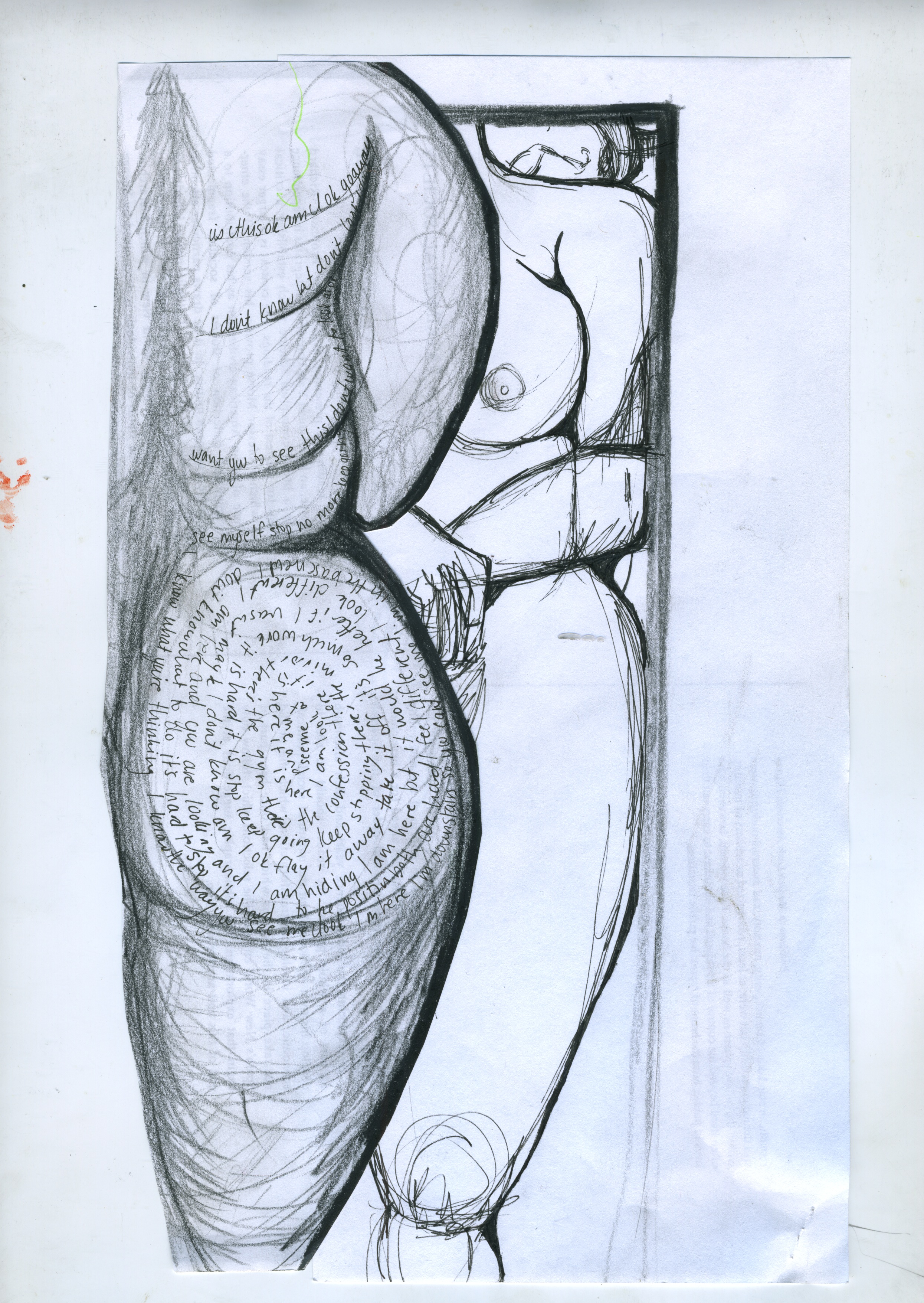

by Nicole Wilkinson; illustrations by Sarah Ross

[Trigger warning: discussion of eating-disordered behavior]

It’s the start of the semester. I’m at the DEB store in the Citadel Mall, looking for some new jeans and shorts to start out the year. My girlfriend occasionally finds something my size and hands it to me over the changing room door.

I’ve been working out all summer, going to the gym every day, eating healthier and feeling great about my body and what it can do. The jeans I'm trying on are the same size as the ones I’ve been wearing for the last few months—surely, these will fit after all of my hard work.

But pair after pair doesn’t quite work—these won’t button, these are too tight in the thighs, these are uncomfortable. Each pair that doesn’t fit is a new failure, but I finally find a pair that fits and is comfortable.

I scowl at myself in the mirror—I can’t tell if I don’t like the jeans or just what’s in them. But they’re all I’ve got, so I begrudgingly pull the pair off my legs and go to the counter to buy them, my mind racing all the while. Am I a size bigger now? I’ve been doing what I’m supposed to. I’ve been working out. I’ve been eating better. How is this possible? I feel so much healthier, I shouldn’t be bigger than I was.

After checking out, I find my girlfriend. I imagine telling her, “If I’m actually a size bigger after all that work, I’ll kill myself.” I think of saying these words like I would say a joke. But I don’t, because we’d both know it isn’t.

I didn’t always hate myself.

Perhaps hate is a little strong—I didn’t always view my self worth as inseparable from my body.

There were a few years of my life in which I managed to view myself as a being that existed outside an aesthetic system of value, and while I can’t remember the exact moment this changed, I do have a memory of the turning point: I’m about 7, maybe 8. I have horseback riding lessons that morning. My mom makes me breakfast, and before I can start digging in, she says something to me, something about my body. She walks away, and after a moment’s pause, I declare I’m not actually hungry. I say it proudly, like, maybe if I show her I don’t want food, I will be worth more to her. We leave for horseback riding, my stomach growling the entire way there.

At the lesson, I’m riding my horse around the barrels with the other kids. My stomach is churning from the combination of heat and hunger. And then I feel it. I struggle to get off my horse and run across the dusty field. I get as far as I can but not far enough. The others get an eyeful of me grabbing on to a wooden post and vomiting into the dust. The instructor sighs, rolls his eyes and calls my mother to come pick me up. I hold on to the post to keep from falling over until she drives up and hauls me into the minivan. As I’m driven away, I can see the kids watching me.

This is my first memory of viewing my body as more valuable empty than full.

It’s not long before I see eating as an act of making myself worthless in the eyes of others. So I figure: if people don’t see me eat, then they won’t know how worthless I am.

I try to eat only when no eyes are on me. I start waiting for my family to sleep or leave the house. Middle and high school are defined by baggie hoodies. Loose shirts. I want to keep things secret, hips that bloom during puberty, breasts and thighs that touch, the human need for food.

There’s food stored in the basement. I start spending my nights there. I eat when I’m not hungry, because even when my stomach is not hungry, there is always something I desire that I can’t have. I eat until I’m sick—it’s the closest I can get to happiness, but that isn’t saying much. It takes me years to put a name to this behavior—binge eating, and to put a name to the condition: binge eating disorder.

At night, I dream of taking a knife and flaying away the layers of skin, fat, muscle, bone. I wonder if it’s possible—if I could just cut away some of the fat on my body. I can’t quit eating cold turkey (though God knows plenty of us try) but I wonder if there was some way to reverse the damage of eating. The Internet provided the tools I wanted.

There are communities online that promote eating disorders as a lifestyle, and most people are aware of them. Pro-ana (anorexia) and pro-mia (bulimia) forums run rampant across social media, despite the ban many websites have placed on content that promotes eating disorders.

I wrote for my high school newspaper, and upon learning about these groups, I figured I’d write an article on them. I started my research with an attitude of disbelief. I scrolled through the pages of body shaming, “thinspiration” and advice to suppress hunger and activate gag reflex. Who would be stupid enough to call eating disorders a way of life?

A month after I started my research, I started purging.

There were plenty of tips online: what to eat to make it less painful, how to position the body to make the food come up easier, how to hide the smell, mess, whatever’s left.

The first time I purge, I’m the only one at home. I get out of the shower and see my body in the mirror. When I bend over the toilet, it hurts. I have to probe and push at the back of my throat again and again. My mind is filled with insults I’d never say to another human being. Once I’m done, I tell myself it won’t happen again, but it does. Again and again.

By the time I get to Colorado College, I’m in recovery. About a block in to my first year at CC, I relapse. Maybe it’s stress. Maybe it’s the fact that when I walk around, hardly anyone looks like me. Maybe it’s the fact that I feel like I can’t eat without being watched. Either way, I end up back in therapy and eventually back in recovery.

This cycle repeats the next year—I’m feeling good, healthy and happy over the summer. I’m back in Denver, and when I walk down the street, I see bodies of all kinds, people smiling and laughing with those who love them, being beautiful in a way I forget people can be when they aren’t thin.

I go back to CC. First block and I relapse again. Now, CC Confessions is in the mix.

A college confessions page is never going to have anything good on it. It’s people posting opinions that are unpopular for a reason. It’s people trying to get a reaction and upset others. However, I think there’s an edge to a confessions page at a school as small as this one. Despite the (poorly enforced) “no personal information or names in negative confessions” rule, it is still easy to target one person or a small group of people. For instance, CC Confessions has lately taken to focusing on trans* people and fat people on campus. Count how many people you know who belong to each group. It’s not many. So, when there’s a confession like “Dear fat girl in the gym, you’re embarrassing yourself,” this confession can feel very intentional.

There have been multiple confessions to this effect, as well as confessions suggesting that fat people are used as thinspiration for others. There’s a reason I drive 15 minutes to go to 24 Hour Fitness. There, I’ve always encountered politeness and a wide array of bodies. Everyone is supportive, non-judgmental and perhaps most importantly, everyone’s a stranger. I don’t want to sit next to someone in class who, just the other day, used my body as a reason to go that extra mile on the treadmill.

This year, thus far, I haven’t relapsed. No binging, no purging, despite the thoughts of occasional, creeping self-hatred I can’t always get rid of. One way to quiet those self-hating thoughts is to surround myself with positivity—which is where the dreaded fat positivity movement comes in. Hounded as a glorification of unhealthy eating, the fat positivity movement has met a lot of scorn. Critics would argue that an unhealthy body should not be a loved body.

Plenty of healthy bodies go unloved because of the unrealistic expectations set for how we are told we ought to look. I know this because when I look back at my pictures from middle and high school, I don’t see a fat girl looking at me from my computer screen. I see a girl with a body type I wish I had now, athletic from years of basketball, skiing and of course, horseback riding. Thin, beautiful—I can’t make the connection between how I thought I looked then and the truth of how I actually looked. It’s like looking at a stranger and being told it’s yourself. I can’t help but sit there and think, Why did I hate myself so much? I can’t help but think that maybe if someone would have told me I could be worth something, no matter how I looked, I’d be in a better place today.

Nowadays, I am actually fat. Every day is still a struggle to tell myself that this adjective does not hold a negative value, it’s just a description. Every day is a struggle to look in the mirror and like what I see. This struggle doesn’t really come from how I view myself, but rather how I am told people see me.

I know this distinction because when I am in my apartment naked (as I often am) and I see myself in the mirror, when I see my girlfriend come up behind me and wrap her arms around my waist, when I hear her call me beautiful, I can feel myself get one step closer to believing it, even when I’m alone.

Despite the fact that I am currently at the highest weight I’ve ever been, I have never been able to look at my body with as much love as I do today. It is because of that love that I can eat without purging, without hiding, without hate. It is because of that love that I feel excited to go to the local 24 Hour Fitness every other day. It is because of that love for myself, the whole picture, that I can look in the mirror without immediately wanting to go spill my guts down a drain. These days, I do a gut-spilling of a different nature.

As a performance poet, I’ve had to master the art of vulnerability, this act of telling everyone the truth of who I am, how I am, how I’ve binged, how I’ve purged, how I’ve hated, how I’ve loved. I do this all for one purpose: Maybe, if someone is struggling like I did, and they get to hear what I wish I heard back then, maybe they’ll be okay in a way I never was. It can be a bit of a stretch to hope I can make that significant a difference, but on my least hopeful days, I try to picture myself at 10 years old. She’s sitting in the front row. I imagine every word coming from my mouth to be just for her, to be one more iteration of the words: I love you. I love you. I love you. Please, understand that you are worth so much. Please, understand that you are loved.