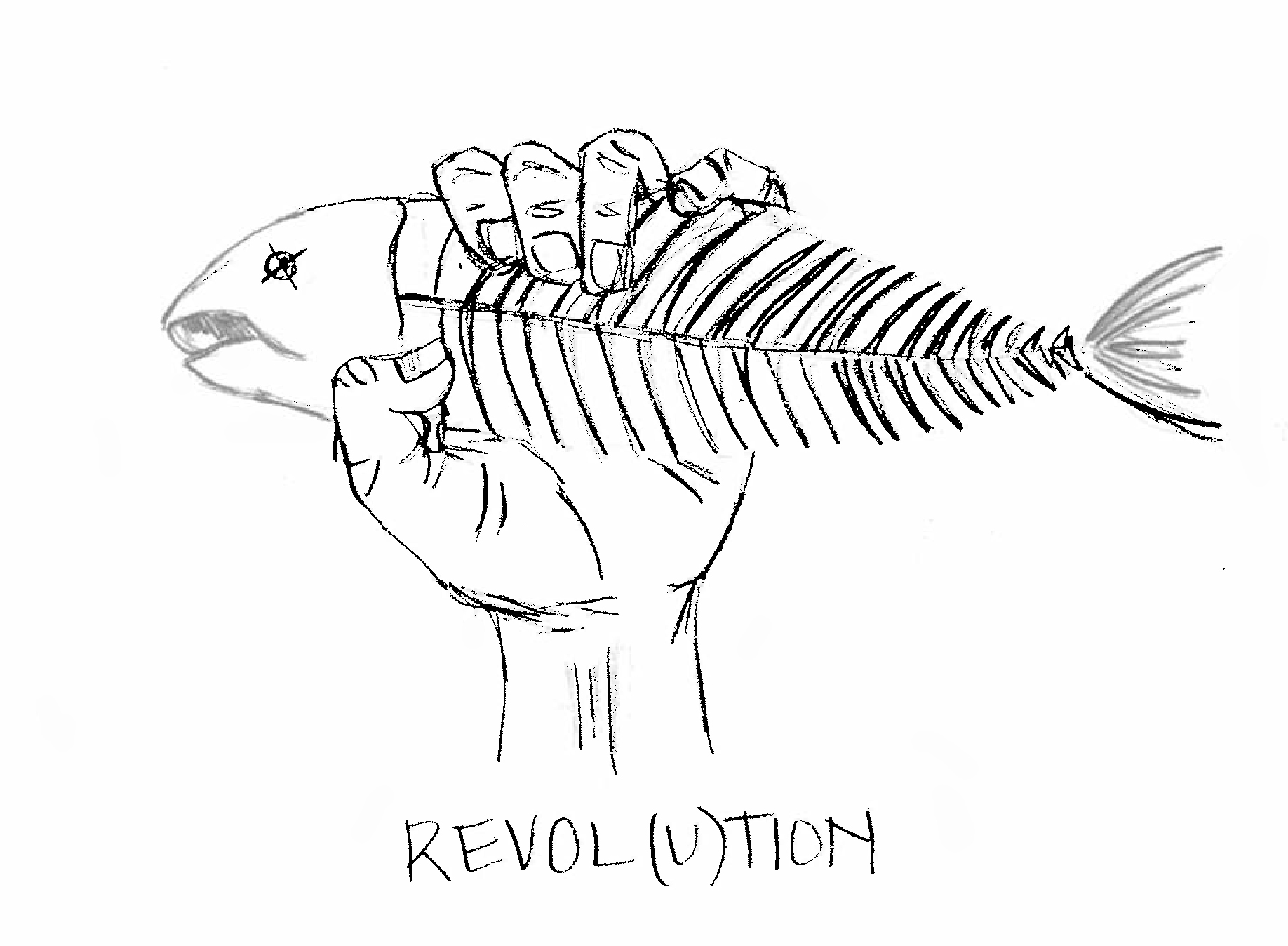

Digesting a revolting food paradigm

by James Dinneen; illustration by Celia Palmer

The worst food I have ever eaten came from a small roadside convenience store in Redwood National Park in Northern California. I was something like eight years old and I chose an egg salad sandwich from the poorly stocked shelf. When I peeled off the shrink-wrap I saw that the moisture of the egg salad had seeped through the bread and congealed into a skin around the sandwich. I was very hungry so I bit into the slippery thing anyway. The flavor of the oozing egg and white bread that coated my tongue and the back of my teeth was far stronger than it should have been. It tasted like a wet chunk of liver, reclaimed from a few-days-dead goose. I choked down the sludge and started to cry. An earwig climbed out of my bite mark.

Profoundly disgusting experiences of food are uncommon. All of us live our lives feeding on things that are monotonously decent. Even our worst experiences of food are just experiences of food that failed while aspiring to be good. Our idea of what is disgusting, and therefore our entire sense of taste, is severely restricted by the fact that everyone is always trying to make food that tastes good.

The dogma that food should taste good, yummy, nom-nom makes sense. Food is more intimate than any other art form. We lift it from the plate and put that shit inside of our mouths (in contrast to the relationship between a painting and its audience). Such an extreme intimacy between food and its eaters has forced foodmakers to yield to their audience’s convictions and comforts more closely than in any other art. I am not suggesting that no one is experimenting with food. Of course there are geniusesin the restaurants of the world who push the boundaries of what is possible with flavor and the eating experience. But they are only pushing the horizon of “good” food. This commitment to food for pleasure is the fundamental ideology of the Good Food Paradigm. And as long as the Good Food Paradigm dominated, food cannot realize its complete potential in flavor or as a powerful art form.

But our Good Food Paradigm (a coinage for the ages I hope) has a more insidious effect than restricting our taste buds. It has limited food as an art form to an art obsessed with the satisfaction of its audience. If we are to free the art of food from the pleasure of the eater and grant it a new role as a dynamic form of artistic communication, we have to learn the importance of disgusting. We have to adopt a Revolting Food Paradigm.

The advent of a Revolting Food Paradigm would marshal a new and exciting arena of foodmaking. A Revolting Food Paradigm is the first and necessary step in creating food art that frees the experience of eating from the biological necessity of eating. People eat food because they are hungry or to satisfy a craving caused by some real or imagined nutritional lack. The biological purpose of food has limited artists since the inception of the culinary arts.

Like other art forms whose purpose is not to sustain life (no one would die without paintings), culinary efforts made not for the sake of sustenance, but for artistic expression, would prioritize artistic communication over survival. Food as artistic communication is a difficult idea for us who are so steeped in the doctrine of the Good Food Paradigm. When is the last time you thought about the symbolic meaning of the coffee at Wooglin’s before thinking about how excited you were for the caffeine? But even when food is meant to be symbolic or to communicate something, its role in the Good Food Paradigm dilutes its message.

A bake sale raising money for a charity is an example of symbolic food within the Good Food Paradigm. The goods sold have a meaning beyond the pleasurable experience of ingesting a brownie or a cookie—they are symbols of having given to charity. But when the buyer of one of those well-intentioned muffins actually eats the thing, the symbolic importance of that muffin is veiled if not obscured by that muffin’s role as good-tasting sustenance.

But imagine a bake sale with revolting baked goods. Not poorly made goods, but cakes designed to disgust. Cookies advertised as revolting. Objects that no one could possibly want except as a means of charity. The message of buying and eating those revolting baked treats would be clearer and more affecting for their eaters. A revolting bake sale illustrates how a consumer would be forced to recognize the symbolic message of food. Its role is primarily an expression of the foodmaker, rather than for the pleasure of the consumer. Perhaps the goods from a revolting bake sale would symbolize the commitment of the eaters to the charity- not just their commitment to snacking on a scone.

If an artist has something important to say, he runs the risk of camouflaging his message in a pleasureable experience. If his message can be communicated through a means that is not enjoyable for an audience (and the artist thinks the message important enough to bare the outrage he will likely ignite) then he should communicate his message that way.

The idea of food as artistic communication seems foreign to us because it is new. To those of us who are truly lost in Good Food Paradigm it probably doesn’t even make sense. But I can imagine a future where, in certain arenas, food is the central artistic mechanism for real discourse clarified and directed by displeasure. The physical qualities of food make it the perfect medium for discomfort. There is no art that can more intimately disgust its audience than food.

Instead of burying our faces in popcorn when we watch a documentary about say, the treatment of pigs on huge commercial farms, why not force ourselves to eat pork prepared by a foodmaker of the Revolting Food Paradigm while we gag at the film? It would be horrible and unpleasant but isn’t that the point? By the credits, we’ve been bombarded from inside and outside by this unignorable message. We’ll leave the theater with revolt on our minds because of the revolt in our stomachs.

I am no foodmaker. My imaginations of what is possible in a Revolting Food Paradigm are the ideas of an outsider. But it only takes one to start a revolution. So if you are a foodmaker reading this, I appeal to you: just once, apply your culinary skill to disgusting somebody. See what happens when you revolt. I truly believe you will discover something amazing. Worst case, it will just be another bad egg salad sandwich.

Adison Petti