Destigmatizing male body image issues

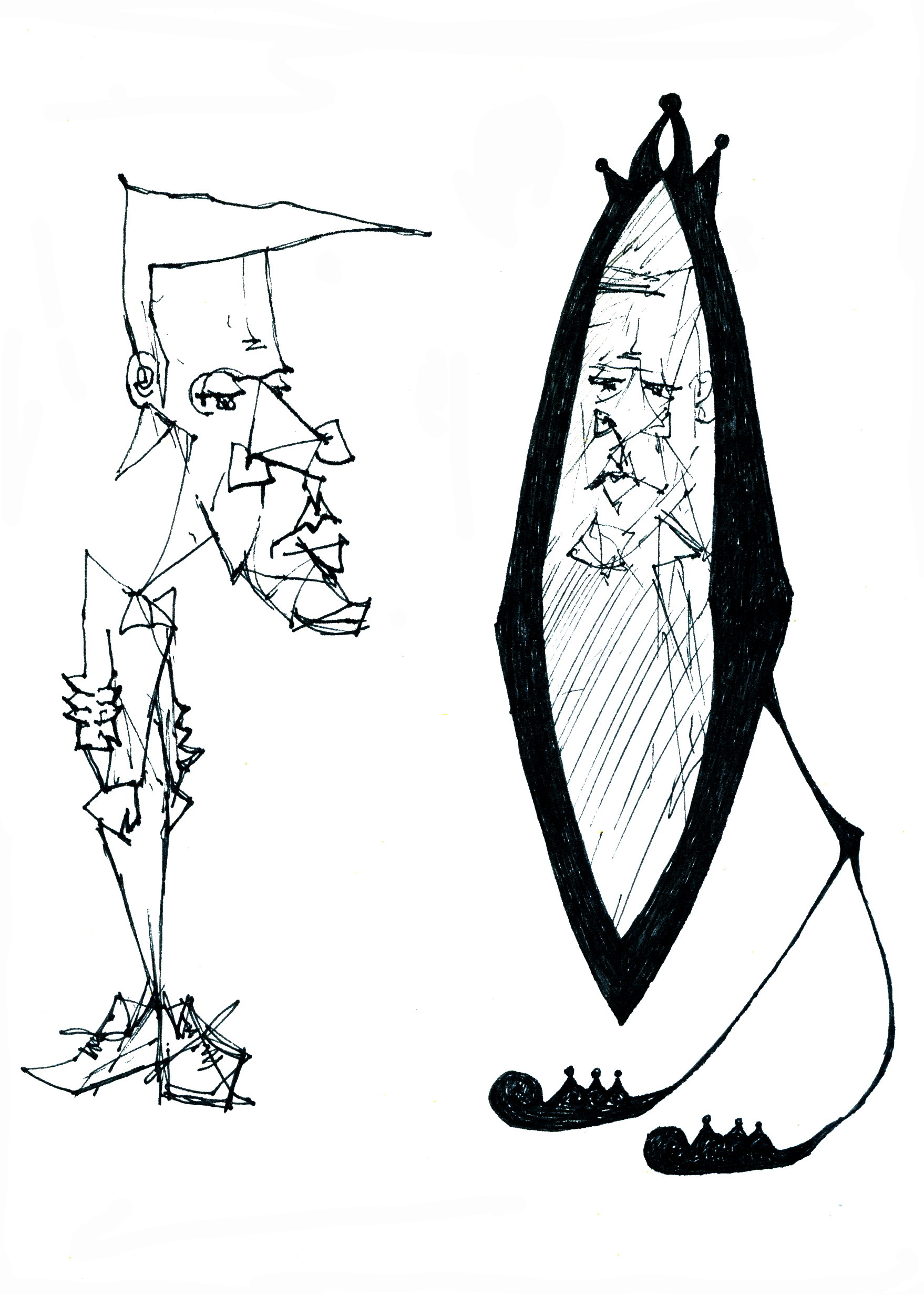

by Sam Tezak; illustrations by Max Ross

At the end of this past summer, I remarked to my little brother that I hadn’t seen him doing much else except for physical fitness. He casually responded, “I would never want to have your body.”

That stopped me in my tracks. Okay, he’s 15—15-year-old boys can be shamelessly critical—and his all-boys school mentality and obsession with sports and girls has seeped into his mind. Right? No, it’s not right. I stood in front of my brother, the one I pride myself in influencing so greatly, and he stood there sweating, with a body I may never have, his friend nearby, fresh off a set. I felt powerless. I tried to let go of how emasculated I felt because of my kid brother’s ridicule, but I couldn’t let go.

For most of my life, I averted my attention from body insecurities. Now, I feel compelled to share the circumstance that wrenched me out of this suffocating naïveté and my realizations following this triggering experience. These pressing and specific stories are just pages and chapters in communion with a larger story of shame that plagues our culture.

I am a man, six foot one, 180 or so pounds, with brown hair, brown eyes and white skin. I casually played sports for much of my life, performed well in school and found pride in being involved with the communities I live in. I have two loving parents, two hardworking and inspiring siblings, and a long list of comforts I enjoy daily. And therein lies the issue. For the most part, I couldn’t believe that body self-consciousness could surface for someone like me. I had never found myself in discourse with another guy about this issue and when I did feel insecure, I pushed it away. But body insecurities manifest themselves in what seems like an endless list of ways. In many cases, there is a figure of perfection or an ideal, and the insecurity lies in the vast mental distance between reality and that ideal. For a long time, I ignored the practically unviersal experience of body self-consciousness and, ultimately, how body insecurities developed in my own mind and affect me day in and day out.

That was until this past summer. I came home after a brutal semester flushed with anxiety, stress and days thick with a regimented schedule—nights distilled by parties and their constituents. The “work hard, play hard” attitude took a toll on me. I came home to discover that my brother, five years my junior, had excelled in his first year of high school, playing football and achieving a spot on our high school’s prestigious lacrosse team while remaining a competitive student and ever-active socialite. Every day for my two weeks home, I could find him working out: hitting the free weights in the garage, biking to the YMCA to workout, attending lacrosse camps and growing larger with each fitness class. He was, and is, obsessed with his image and physical skill.

As an older brother, I felt proud. I introduced him to lacrosse and he played football on the team I did. Hearing about his achievements, his happiness and his indomitable work ethic fill my heart. So when one early afternoon in June I walked into the garage and found him sweating after a work out, his lifting buddy on the bench, I never expected to be so hurt by his words.

I developed a hyper awareness of everything I consumed: Great, no more cigarettes and cut down on drinking. Those are good things, but what else is a good thing? How about no more sweets, they’re packed with sugar. I’ll throw out pasta, it seems to be a burden on my body. And then it began to escalate: In addition, I’ll eat breakfast, no lunch, bike the city all day, workout and maybe eat a salad for dinner. I can’t develop the Hercules-esque body my brother has developed, but I can thin down to the point that he has almost nothing to critique.

I believed that if almost nothing were there, there would be nothing he could say. Meals went from intimate experiences with friends and family to a self-critical, half-hour examination. I felt disgust and horror with each bite.

And my disgust didn’t stop with what I consumed. I began to obsessively look at myself in the mirror. I weighed myself daily and developed a demented perspective of myself, continually criticizing who I was. My brother had dealt me a blow so menacing that I couldn’t escape it. I felt a loss of influence, I felt less of a man, and for these reasons, I felt that I had lost my identity.

Body insecurities are not limited to one gender and they manifest themselves in so many ways that it can be impossible to compartmentalize them all. My personal insecurity prompted me to thin down, or at least to appear thinner.

My brother’s comment also made space for meditation. This body insecurity didn’t feel necessarily new to me. In fact, it startled me because it seemed to be something I dampened with gender constructs: that as a man, I shouldn’t care, I should brush this off without even consciously doing so. I began to consider how body insecurities may appear for other people, beginning with my family.

Body insecurities are laced in my family history, but until now were silenced by a collective, multi-generational demonization of “fatness.”

My mom was born and raised in Nashville, TN, capital of country music and home cookin’. After preparatory school she enrolled at Vanderbilt University. Looking back on these years, my mom would never fail to tell me a few things: she was the photo editor for The Hustler, she played on their first women’s soccer team and she was fat. She would remark that when she came home from school for Thanksgiving break, my grandfather reminded the guests not to pass her the rolls, “she already has enough.” This is the same man that once yelled, “come on, big mama, come on!” to a nearby woman eating a massive steak at a Texas roadhouse. And as a kid, these stories never struck me as odd. My mom never explicitly told us that she was affected by these attitudes. Yet, she runs, bikes and swims every day, completing marathons and relays on the side.

In fact, the only time “fatness” surfaced in my mind was during our annual visits to the South. There I encountered the extremes of obesity and eating disorders, and felt terrified. This stimulated a blind pride for my state, which had always been recognized as the happiest and healthiest above the rest. In fact, without even consciously doing so, I assumed the identity of my grandfather at the dinner table 20 years before, casually commenting to guests about my mother’s weight. But instead of objectifying my mom, I objectified anyone that was less than “in shape”—or two thirds of the population in America alone.

When my sister came home from Tajikistan after a summer of learning Tajik Persian, immersing herself in a new culture and inevitably gaining weight from actively practicing Tajikistan eating habits, she yearned to change her image. In Tajikistan, eating together and eating large amounts is common, if not celebrated. But after less than 24 hours on Western soil, she now fought against the weight she gained during her immersion there. Her body anxiety was one of the first things she mentioned to me after not seeing her for several months, and I didn’t understand. I tell most people I meet that my sister is a badass. She works harder than anyone I know, she cried when she got her first and only “B,” and she spends the majority of her time to working with children with autism and Down syndrome.

My inspiring sister felt imperfect and I worried how that would develop. This pressure on herself really came from a culture that does not see past image and, more importantly, a family that sets a precedent on perfection, including body perfection. Nothing caused me such pain and awareness than to realize what we were sharing between ourselves. To this day she complains about living with my exercise-obsessed brother and mom. And this claws at my heart. But it also reminds me of the power that actions and words yield.

In no way do I suggest that I am grateful for my brother’s unsolicited critique of my body. But all the same, it compelled me to be more aware of an issue I formerly believed only pertained to women. It certainly manifests itself differently, but this instance provided me with the vocabulary and tools to investigate a much larger, looming issue that silently and loudly pervades our culture.

Thanksgiving is coming right around the corner and with it, I may be back home in Denver, reunited with my family. Since the last time we sat down at the table, I have confronted my body insecurities for the first time. By speaking about these image issues, I’ve gained the tools to confront unintentional pressure from my family life. When I sit down and break bread with my kin and talk with my sister about her college applications, the body image criticisms dealt by my grandfather decades ago and the hurtful words handed to me by my brother will not be sitting with us.