There are alternatives to dissection. However, many alternatives are quickly discounted because of the institutional strength of dissection as a scientific tradition. The National Association of Biology Teachers “supports the use of these materials as adjuncts to the educational process but not as exclusive replacements for the use of actual organisms.” Many alternatives are dismissed because of how new and underdeveloped they are, but as technology advances, more and more sophisticated dissection alternatives are becoming available, and we should give them a chance.

One alternative to ordering from a dissection company that still allows for physical contact with a specimen is to use well-preserved specimens like those from the museum that I used for my biology class in Australia. The lab’s focus was all orders of terrestrial vertebrates (mammals, birds, reptiles, and amphibians), and the specimens were preserved in a variety of ways. Some were stuffed, some were just skeletons, some were just furs and skins, and others were chemically preserved as whole or partially dissected organism. While wearing gloves (to minimize degradation of the specimens), we were able to pick all of them up, move them around, and interact in essentially the same way as we would with a newly dissected specimen. There were additional benefits to this type of variety, since you could observe the skeletal structure of a body region in one specimen, and the exterior and interior morphology of the same body region in another.

There is a similar opportunity at CC, due to our extensive collections of birds, mammals, and insects. The school has a similar variety of skins, skulls, skeletons, eggs, and nests of birds and mammals. The collections cover 425 species of birds (700 total specimens) and all mammalian orders found in Colorado. I personally was able to use the bird collection during my ornithology class. Again, with the ability to pick up and manipulate any of the structures (with gloves of course), I was able to learn a lot about external bill, wing, and feet morphology, along with the internal skeletal and muscular morphology. The bird collection was assembled from 1860-1950, and the specimens are still intact today. This option reduces the need to order new specimens for every single lab, and provides an additional level of variation for students to learn from. Furthermore, the longevity of the specimens allows the time to source deceased animals from local zoos, wildlife rehab centers, or other locations that promote animal welfare and conservation. There are other alternatives, though, that don’t involve the use of any animals.

The first is of course online websites, videos, and tutorials. Carolina Scientific sells a software called eMind that allows you to virtually interact with all the specimens that you could have ordered from their site. For example, you can click through the digestive anatomy of a frog, and when you click on a structure, it will tell you what it’s called and what its function is. There are similar websites listed on Colorado College’s website for the neuroscience course that allow you to learn nervous system tracts by going through images of brain slices. These sites will quiz you on the tracts and structures, and have information about names and functions stored for easy accessibility.

Websites and software like these are widely available for most specimens and systems you might need to learn, but how do they compare to dissection? They have the obvious benefit of not harming animals, but they also have a lot more information readily available information. Many have the built-in function of quizzing you, and best of all, they allow more individual and continuous access. During a lab, you might share a specimen with another student, and you may only have an hour or two to spend on the dissection, but with these websites, you can access them on your own time and go through them at your own pace. The only question remaining is how much does the kinesthetic aspect of a dissection matter: does being able to physically manipulate structures drastically improve learning?

A study done in Australia (where legislation requires the use of alternatives where appropriate) compared actual dissection with alternatives in undergraduate human anatomy and physiology courses and found that they were generally equally effective. Of course, this is just one study. Many still advocate for the role of kinesthetic learning in dissection labs, which many alternatives still incorporate.

One example is right here at CC: plastination. In the Introductory Psychology brain anatomy lab, instead of using cow or sheep brains, we use plastinated brains. These are real, donated human brains that have been treated with a series of chemicals that cause the tissue to feel like plastic, but retain its form very accurately. They can be picked up, and turned over, and they are split into the two hemispheres, so you can view the cortex as well as the subcortical structures like the thalamus, corpus callosum, hypothalamus, ventricles, etc. These have the benefit of showing the amount of individual variation in brain structure, allowing the students to practice structure identification on highly varied specimens. Another benefit is that they do not need to be kept in any special chemicals or location. They are always available in the brain anatomy lab, and students can use them to study whenever they need.

Plastination can also be used on other organs besides the brain, and even medical schools are using plastinated organs to teach anatomy. One study found that 39% of medical schools use plastinated specimens for education, but the main reason for not using them was that they don’t provide the same learning experience as the physical dissecting process. The same could be argued for the brains at CC. In the neuroscience course, to further students’ understanding of neuroanatomy, they dissect and stain a cow brain, and are thus able to cut apart the brain themselves, watch the structures appear, and get practice locating them in a more dynamic and challenging environment. Is this something that can ever be replicated by a dissection alternative?

There is one very new alternative that comes extremely close to actual dissection: virtual reality. This method provides not only the abundance of information associated with structures, but it allows for both the kinesthetic manipulation of specimens and the physical act of uncovering less superficial structures. The use of this alternative is actually already in the works at CC. The XR Club, run by Galen Duran and Madeline Smith, has been using the technology to run review sessions for human anatomy students, one of which I attended.

With the software for human anatomy, you step into a room with a skeleton in front of you, and you have an entire wall of options. You opt for looking at bones, muscles, nerves, vasculature, movement, or an individual system. Whatever you select appears in front of you, and you can walk around it (even through it, as one student discovered by sticking her head into the ribcage of a skeleton), select structures to get more information about their function, and even pull them apart. As a neuroscience major, I of course pulled up the brain (cranial nerves and vasculature included), and took off the cerebral cortex, then the thalamus, and then I took half of the cerebellum out and rotated it around so that I could look at all sides of it including my favorite view: a sagittal cross section. The clarity of it was spectacular, and I could see each branch of the tree-like organization of the cells in the cerebellum.

As I stuck around to observe, other students used the software to overlay different systems that they had only studied individually, and said that it helped them better visualize how everything related. For example, viewing the nerves, muscles, and bones of the legs all at once and being able to remove different structures to see the deeper muscles was a great study tool. All of the information in the simulation shows up on a TV screen, so if you have a learning assistant or professor nearby, they can see what you’re seeing and answer any questions you may have.

These review sessions, according to Smith, are very new and just starting to gain popularity, but so far the professors have been quite receptive to it. Medical schools have already started utilizing more advanced versions of this technology to practice dissections, and with its continued development, these versions will only get cheaper. In the future, undergraduate students could be completing entire dissections virtually.

For now, though, the XR club is working to increase awareness and accessibility of this technology by hosting these review sessions and looking into other VR packages. The goal for the anatomy program isn’t to replace the cadaver lab, since those are ethically and willfully donated, but in the context of nonhuman animal dissections, this option could be a promising alternative. VR packages for nonhuman animals are sold by our favorite company, Carolina Biological (partnered with VictoryVR), and they even come with a virtual professor that will review the structures with you when your professor isn’t available. The packages so far include cats and frogs, but more species are in the works. One consideration with these options is that they still have to use many animals to perfect the virtual image, but once the package is developed, it can be used indefinitely.

If you are feeling conflicted about performing dissections, there are definitely alternatives. The questions that remain are just how willing professors are to adopt them, and how far they will take you in your scientific education. For example, if you are studying to become a doctor, will there always be a point at which you have to stop using alternatives—or could the technology become so advanced that we could train doctors solely using alternatives and donated human cadavers? The same goes for future researchers. If they don’t practice on real animals, will that then decrease their ability when working with real subjects in a research lab? With the rate that technology is advancing though, it seems that alternatives will be put into practice at higher and higher levels. And ultimately, how effective these alternatives are is determined by the students using them, so it is up to us to be vocal about what we want our learning to look like.

As we start replacing dissections with alternatives, it’s important to consider how the use of these alternatives will impact animal welfare as a whole. Due to how far removed the dissection specimens are from their original source, alternatives may not directly reduce the death of animals, but removing a justification for animal exploitation could discourage both producers and consumers in other sectors such as the meat and breeding industries. Furthermore, removing this violence against animals, especially for younger students, could chip away at this ingrained mindset that we develop from the normalization of nonhuman animal exploitation.

To me, science doesn’t have to involve flexing how tolerant you are of exploiting animals. Many scientists, such as Lori Marino, who is coming to talk at CC in Block 7, have used science to gain a better understanding of the worlds of other species, and have used that information to protect them. She does research on the brains of cetaceans (whales and dolphins) in order to demonstrate why they should not be kept in captivity. The more we know about other species, and the more we know about technology and alternatives that can reduce their suffering, the more responsibility we have to do so.

Science is about gaining an appreciation for the world around us, and in that way, it’s inherently empathetic. This is what we should be passing on to future generations: science can be kind, science can be transparent, science is ever-evolving and can grow to incorporate new alternatives. Science is about breaking down old paradigms and saving all lives—not just human ones.

By Courtney Knerr

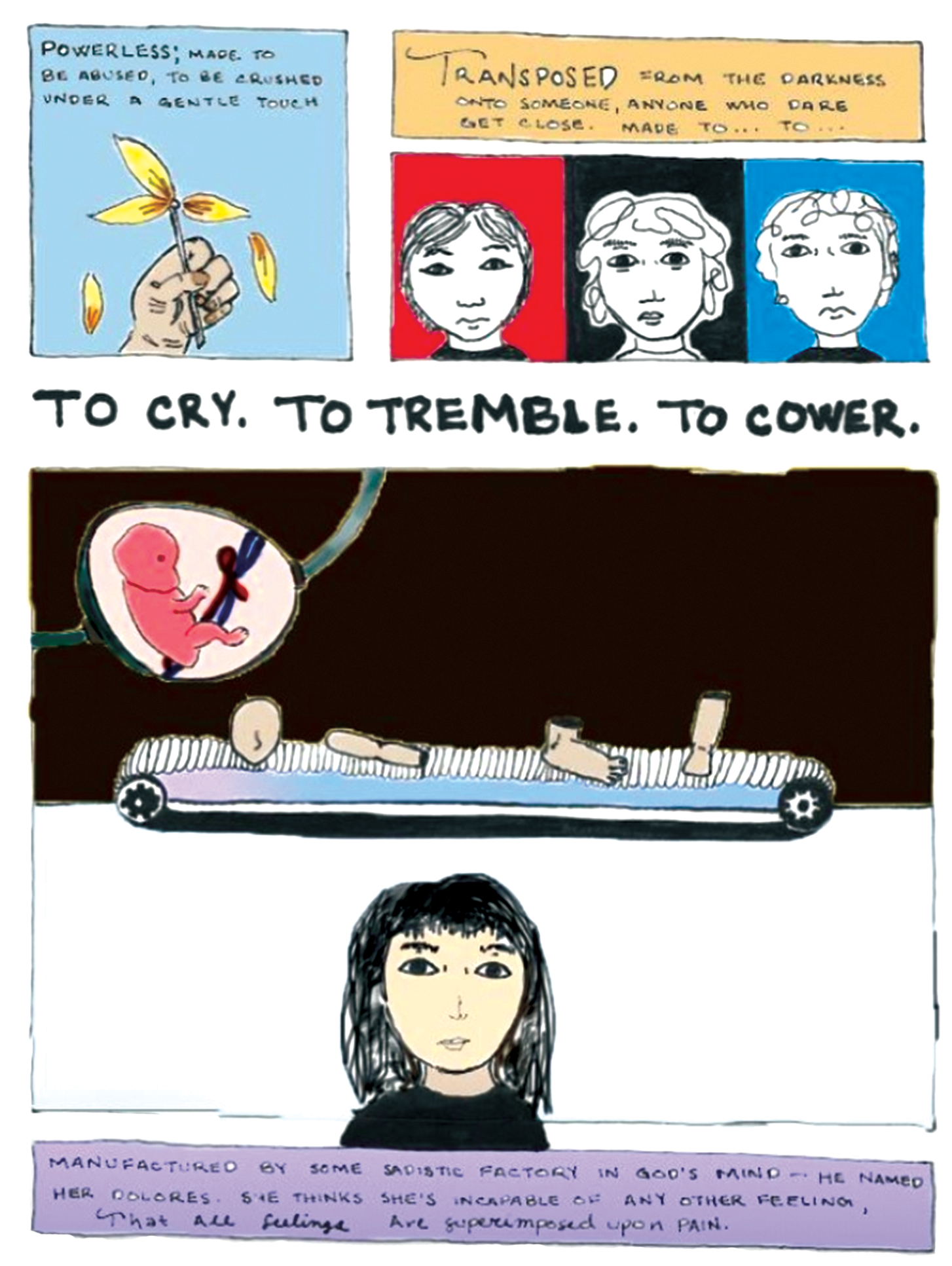

Art by Jessie Sheldon

Body Issue | February 2020