A River Runs Through Me

I met him at fourteen. I’ve been grasping at a ghost ever since.

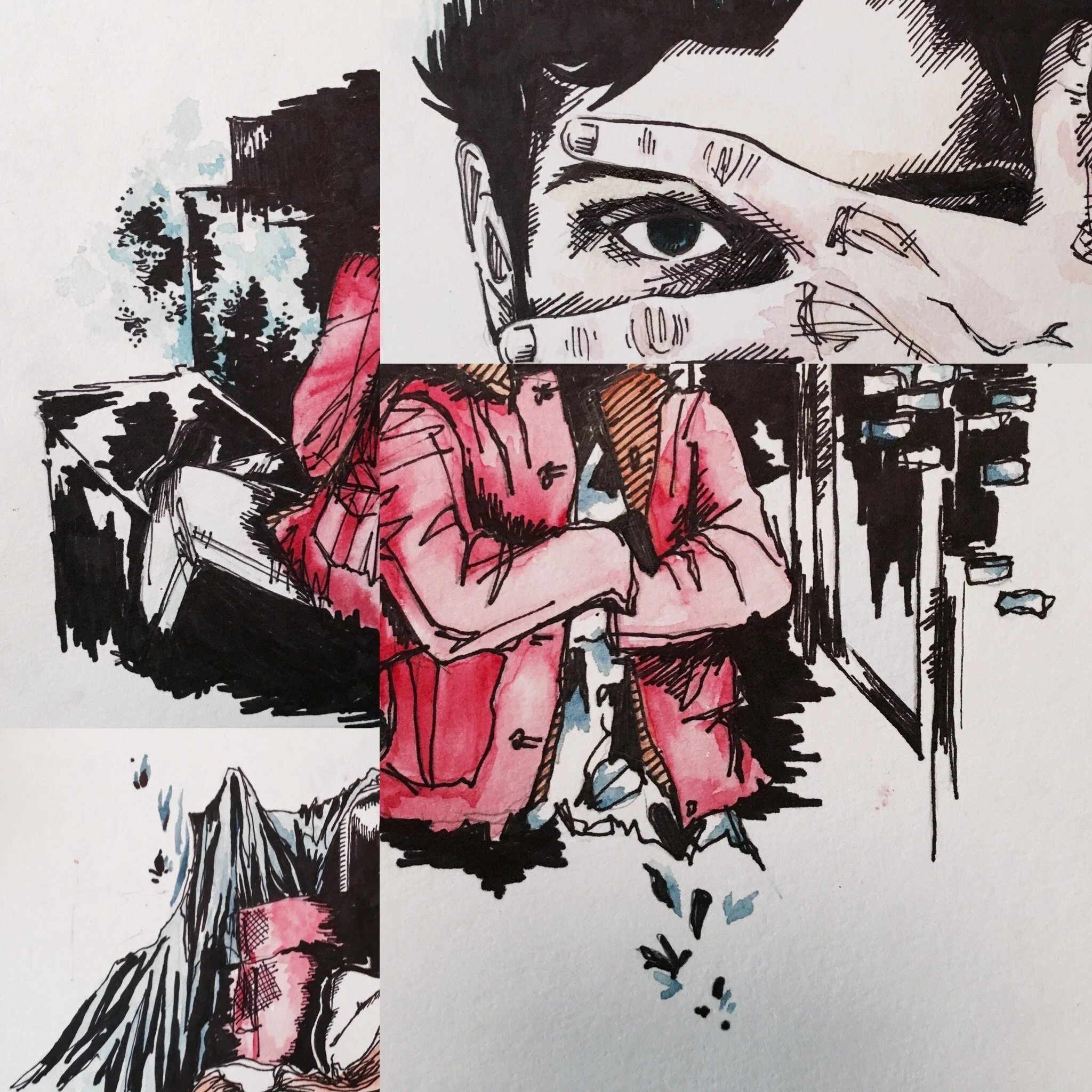

Article and art by Jane Harris

Content Warning: Substance abuse

It’s coming back in waves. Our Stand by Me narrator, an author remembering the death of his childhood best friend, seems caught between two worlds as he stares at his computer screen. The hazy, rose-tinted nostalgia of childhood fights to hold him back, to prevent him from what he already knows will happen: the innocence lost upon realizing the dead body his friends went to see in the woods is real, the hindsight that his best friend, played by River Phoenix, will soon be gone himself. The author takes a thoughtful, solemn pause before typing, “Although I haven’t seen him in ten years, I know I’ll miss him forever.”

Stand By Me, 1986, playing on my mom’s laptop that I’d stolen for a late-night movie, cuddled up in my dad’s childhood bed at my grandparents’ home. That was the first time I saw him. The setting, in retrospect, was perfectly primed for nostalgia. The night, hot (in the way only a West Virginia summer can be), the screams of the cicadas, deafening (the only sound that could be heard for miles), the hour late (well past midnight). I was fourteen when I watched my first film with River Phoenix in it. I fell in love in a way I’ve never fallen in love in my entire life; I fell in love with the depth of emotion I saw flickering across the LED screen. I was entranced, left staring at my own reflection in the dark when the credits had finished rolling, too stunned to close the computer. I didn’t sleep a wink.

He’s dead, he died years before I was born. I found this out during my post-movie-watching trip to Wikipedia, absolutely desperate to learn about this actor I just ‘discovered’ by myself as my eyes struggled to adjust to the computer’s change from soft black to bright, LED-white light. I had to look him up. I was enthralled with his character in the movie I’d just watched— I saw myself in Chris Chambers, a loyal friend, unafraid to be vulnerable, not concerned with being ‘weird.’ I thought, at that moment, I could do to be more like him. When I first saw Stand by Me, I had just graduated the eighth grade, and had realized how much of the last month of middle school I’d spent trying to fit in with everybody else. I wore a Lilly Pulitzer dress to my Catholic school’s graduation mass, eager to please my mom by wearing something nice, desperate to fit in with the other, far more popular girls. It was pretty, but I was uncomfortable in the way softer fabric couldn’t change. I only wore it once. The entire summer after, I lived in Nike shorts and graphic t-shirts from Hot Topic. High school was looming in the future, only a short couple weeks after my annual trip to my grandparents’, and I felt threatened, terrified. High school would start in no time at all, and I would be entering into a new social world with no friends from middle school to hold my hand, no one to help me navigate the sheer size of the new building nor the pyramidic new social scene, one that seemed cemented in stone. Already, I had been warned by mothers of family friends to “stay away” from certain girls. I had no idea who I was, and the only thing that seemed to bring me actual solace was escapism. In the months following my introduction to River’s work, I thought of him often. I looked lovingly at his face, a million pictures of it printed out and collaged to adorn the cover of my binder for my freshman US History class. Upon learning who he was, one of my high school friends said, “Oh my god, you have to talk to my mom. She was obsessed with River Phoenix when she was younger.”

Lots of people are obsessed with him, I am not unique in the attention I’ve paid to the humble heartthrob. Leonardo DiCaprio has spoken, in interviews recent and older, about River being his “hero.” There’s a video of Leo at seventeen or eighteen, in his dressing room on the set of “Growing Pains,” where he has his hands above his head and bashfully says, “I think I look like a young River Phoenix.” Prior to meeting him, Brendan Fraser thought River would have “a lot of hostility.” Fraser, like many others who saw the image of River’s kindness and couldn’t decide if it was an act or as his genuine self, wanted River to be “standoffish and cold.” In reality, he was “really gentle and sweet.” The façade of River, then, is no facade. He is the kind, giving, and conscious soul reflected in the characters he plays. Desperately, I wanted to be like this. I was enamored, like many, by River’s compassion and how it seemed to pour out of him. At sixteen, when I read what Stand by Me co-star Wil Wheaton had to say about him— “He was this raw, emotional, open wound all the time. He felt everything.”—I saw myself. I see myself at around twelve, unable to stop sobbing and apologizing incessantly after I said “fuck you” to my younger sister for the first time (she didn’t deserve my anger nor did she seem to care, she was young and unbothered). I see myself at sixteen, happy to the point of tears after my little cousin handpicked a dead beetle from my backyard to give to me, saying “it reminded me of you,” thinking to myself that it was the best gift anyone had ever given me. I see myself, now at twenty-two, when I think, selfishly, how sometimes the love I sow for others I don’t get to reap back for myself. Sometimes, in desperation and loneliness, I wish I could take back all the kind, genuine words I’ve given, the song links I’ve shared, the letters I’ve written to those who hurt me, to instead reclaim that love for myself. I don’t, though. River would never do that.

Martha Plimpton, River’s one-time real-life lover, looks at his Running on Empty character earnestly, tears in her eyes and a lump in her throat as she chokes the words out. “Why do you have to carry the burden of someone else’s life?”

As I learned more about River, spending hours in internet rabbit-holes and reading the few physical books written about him, the more I wanted to be like him. I was—still am—a very emotional being, empathic to the dangerous point where I martyr myself on behalf of someone who does not need me, nor asked me to do so. When I was younger, my emotionality seemed like a burden or a curse, something that caused me more turmoil than necessary. I wanted it to be different, I wanted to be like River, whose emotions and feelings seemed revered and celebrated by others who wished they could see the world through his eyes. I, too, wished I could see the world through his eyes. It’s almost comical, now eight years down the line, how I would go on to make River Phoenix an integral part of my personality, inextricably linked to myself in the same way my front left tooth has always had a chip, how my nails are always short, how the one front piece of my hair can never hold a curl. In retrospect, it’s both hilarious and endearing that little me saw an adoption of River Phoenix’s ‘personality’ as the way to come to understand myself and make sense of my ache. It cannot be taken too seriously; if I don’t giggle about ‘this River thing’ silently to myself every once in a while, it all becomes slightly embarrassing. I melded what I viewed his character to be with my own perceived lack. ‘Obsession’ is not the word for the attachment I created between myself and my image of him, I rather ‘assumed’ the traits that I thought River would be proud to see in me. Or, rather, that I would be proud to finally see in myself. I realize that only part of my ‘relationship’ with River Phoenix was like the classic, crazed young girl obsession with an attractive actor. One time, jokingly but sweetly, my sister sent me roses with his name attached. My friends and I engaged in our fair share of lamenting how we were “born in the wrong generation,” as if being born a decade earlier would’ve given us a ‘chance,’ of sorts, with the older celebrities we so loved. I do realize that, had I been alive when he had, things would be different. I think I only attached myself to him because he was dead, because he could provide me a blank slate. He could be, and was, whatever I wanted him to be. And in turn, I could turn into him.

I had no idea who I was. To some degree (one I’ve since made peace with at twenty-two) I still don’t. I was young, anxious, sad in a way I did not yet know how to describe, what words to use to express its depth. In a confusing way, I was angry at how much I seemed to feel everything too strongly. Boys who I thought were my friends in grade school made mean comments to me, ones I brushed away under the pretense that ‘boys are mean because they like you.’ Later, of course, when a certain string of words would sound off a twang in my heart, a drop in my chest, I would remember how much those comments hurt. There were feelings I had at that age that floated around in my body, aimless, with no place to rest. River– or the image of River I created– provided a channel for me to direct those feelings towards, helping me engage in some sort of therapeutic process years before I’d put myself through actual therapy. He became a version of home. Through this version of him which I created, I became more conscious of the way my body and mind moved through the world. He was humble, kind. Therefore, I tried to be humble and kind, talking less of myself and asking more questions of others, sitting next to someone new at lunch on occasion. Most importantly, though, River was a wonderfully loyal friend, a quality I attempted to replicate at fourteen that I’d later curse at seventeen when the closest friend I had been so loyal and giving to quickly ceased to become a friend at all. However, the qualities I saw myself as stealing from River, characteristics that soon became inseparable from my own image of myself, existed before he got to me. He did both nothing and everything at the same time. I always had the potential to be loving, compassionate, in control of my empathy, but I didn’t see it in myself until I saw it in him. Watching My Own Private Idaho, especially, I still feel as if he is looking directly at me, but he can’t quite make out my shape though I can see him clearly. It’s a two-way mirror.

Mike Waters, the narcoleptic street hustler and hopeless romantic River Phoenix plays in My Own Private Idaho, nurses his heartache as he rocks back and forth on his chair, spinning a large yellow flower between his fingers. He turns his head, looks up, and immediately locks eyes with his former best friend, Scott Favors (a.k.a. Keanu Reeves) from across the cemetery. With one twist of the neck and one shrug of the shoulder Mike decides, while holding Scott in his gaze, to mourn him, but to move on. With that, Mike throws his head back and screams.

While River is so important to me, he’s not real. I’ve resigned myself to a constant mourning process and simultaneous constant celebration of the life of someone I never knew, someone I will never know. The River I whispered to about my day before going to bed at sixteen is not the River that his family members are missing every day, nor the one his friends and once-upon-a-time co-workers speak fondly of in interviews. He’s not the River that causes Keanu Reeves to choke up and go silent when he is brought up in interviews. Nor is he the River his brother, Joaquin Phoenix, speaks of feeling “indebted to” when asked how and why he got into acting. Granted, my River is still based upon those public, collective memories. He has the same shy, sly smile in my head as he does in the pictures of his tour of Japan in 1991, blushing at the camera, hair falling in front of his eyes. He doesn’t necessarily want the attention, but he’s thrilled people resonate with his work. He just didn’t want praise for what he did. You can watch him, in interviews from the late 1980s, squirm in his seat, pulling his hands up to cover his face when his acting skill is commended. He also didn’t want to win the Oscar for Best Supporting Actor in 1989, answering the question,

“You’re glad you didn’t win?” with a genuine, honest,

“Yeah.”

It’s not that he was insecure in his acting ability, it’s more that it didn’t matter so much to him whether he would win or lose, nor did it matter if anyone saw his work. It only mattered to him that he was doing what he loved. This quality, assigned to him by others, is one I envied greatly at fourteen. I wanted, desperately, to not care what others thought of me, to be assured and fulfilled in my own hobbies and interests. I was looking to be cool and River seemed, to me, to be interesting in an effortless way. He was genuine, unafraid. I was nervous, self-conscious, and scared to cross the threshold into the ‘adulthood’ that high school seemed to lead me towards. But the fact that River was unapologetic towards his passions meant I could be too. I tried, desperately, to reach towards the things that genuinely excited me, turning to the classically ‘weird kid’ alternative arts, hobbies, and interests. The month before my freshman year, when my summer P.E. running buddy found out I’d been listening to screamo and metal music in my headphones the entire two weeks, she dropped a nearly silent, “Oh.” The day after, I heard her murmur to another girl, “Isn’t that so weird?” I wish I could say that was the last time I let something like that bother me, but I’ve had my fair share of anxious, pit-in-my-stomach sleepless nights. When that feeling struck, for a period in my life as reliable as the sun rising and setting, I had a quick fix. When I didn’t know how to make peace with my loneliness, I’d make friends with a new River Phoenix character.

There’s something that he really wants to say, but the words won’t come out easily. Pained, stuttering, and tearing up, Joaquin Phoenix’s voice trembles as he pushes out the final acknowledgment of his 2020 Academy Awards acceptance speech. The pain never gets better, just easier to swallow. “When he was seventeen, my brother wrote this lyric. He said: Run to the rescue with love, and peace will follow. Thank you,” Joaquin says, backing away from the mic quickly. The audience roars.

I understand that my characterizations of River, though an amalgamation of things I’ve read of him, of what I’ve heard people say of him, aren’t exactly true. In speculation there’s a certain line, one I’m afraid I might’ve crossed in my attempts to re-make River Phoenix how I saw fit. After all, the very thing that drew me into him was the fact that he’s dead. River’s death is clouded in mystery, ripe for baseless rumor about whether or not his overdose was intentional or not. Crafting a persona has its pitfalls, of course, and I’ve spent moments, struck by guilt, staring at my hands, trying to figure out if I’ve done something wrong, if this alignment I feel with River is causing me to lose myself. Where do the lines between me and River start to blur? When do they disappear completely? Would the real-life, living, breathing River have supported this? Most likely not. Of course, for me to ask too many questions of him, to look at a still image, hoping his eyes will wink back at me, is to do his life and his memory a disservice. This person’s pictures adorned my teenage bedroom, the one of him in the suit at the 1989 Oscars on my nightstand, printed on top of a blank polaroid as to suggest historical accuracy, to give the illusion I could’ve been there with him. Another image of him– a painting I made in art class– is taped into the corner of my mirror, his face illuminated in different shades of red (my favorite color), x’s through his eyes. I look at myself and I see his ghost reflected back onto me.

It is surreal now, that I am merely a year away from being the age River was when he died. This realization recently had me tearing up at the dining room table but has also helped clear some of the mystical fog that surrounds him in the memory I’ve constructed of him. He is not the far-wiser, more accomplished, grown-up figure I imagined him to be at fourteen, but rather damned to remain eternally twenty-three. He was young, he was so young. Most likely, he was just as lost and confused in the world as I am. He probably ached for guidance, a hand on the shoulder, in the same way I still do. However, I’ll never be able to return the favor the memory of him has given me. He’ll never be able to use me as a personal compass in the way I’ve used him. Desperately, I want to thank him, though I know I cannot. I sustain myself, instead, via a mental list of our degrees of separation. The director of My Own Private Idaho, and River’s dear friend, Gus Van Sant was born in Louisville, Kentucky, my hometown. Sandra Bullock, River’s co-star in The Thing Called Love, has a sister who is married to a close friend of my dad’s from college. The date of his death is my long-time favorite holiday, Halloween, and his family lived for most of his life not far from my grandparents’ home in Florida. These connections– these links I’ve imagined in my brain with red thread, push-pins, and all–are attempts at rationalization more than anything else. Maybe they could be seen as a way for me to really connect with him, to exist in and love the cities his loved ones did, to touch him through the people I’ve hugged and the people they’ve hugged. I reach out to touch him, and I get nothing. I’m grasping at a ghost. I miss him.

When I say I miss him, I’m really missing myself. Paging through images of him, looking for ones I’ve yet to save to my phone. I am searching to see, just once more, the younger me in his eyes, his nose crinkling, his arm around someone’s shoulder. As most people do with their younger selves, I wish I could hug her. I wish I could tell her that she is doing a truly wonderful job of managing what she is. It gets harder, but in ways it also gets better. She has yet to have the phone call at nineteen that leaves her reeling, sinking into the knowledge that her life, too, has now intimately been touched by addiction and death in the way River and his family’s lives were touched by it. It’ll become very real very suddenly, but she doesn’t know that. The phoenix, conceptually, will also become a big part of my life philosophy. Despite everything that seeks to sear me, to tear me completely apart, I will always come back, reinventing myself in the process. From the ashes, I rise, with the scars to prove it. I want to brace my younger self for this moment. I want to put my hands on her shoulders and steady her. But she doesn’t need me looking back on her from the future, unable to change anything. She has me if she has River.

All the love I have put into this honoring of River Phoenix since I was fourteen, a delicate care taken to learn every detail and memorize every quote, has merely been love and care for myself, a balm for my growing pains. To a younger me, River was a friend, confidant, at younger times an older sibling, at other times an obsessive crush. At twenty-two, the thoughts of him are less frequent since I don’t need him to help me in the way he used to. My love for him remains the same, though. It’s intense, an all-encompassing warmth and buzz that fills up my stomach, chest, and head and comes spilling out of my eyes and hands, my body unable to contain such a sensation. Unable too, until now, to call it self-love. Writing this now, I twirl my necklace, a coin with two phoenixes sitting together on it, between my fingers. It’s been a journey on a long, never-ending, My Own Private Idaho road, a road that goes all the way around the world, to get to the point where I have realized I might just love myself after everything. River has nothing and everything to do with it.